Toponymy is part of the aboriginal mystery that surrounds and challenges us. In the Greater Antilles millions of people live in places with names that originated long before Christopher Columbus set foot on the sands of our beaches. We use hundreds of them, they are part of our geography and our culture, yet in most cases we do not know how they were given and why.

This ignorance could be limiting the possibilities of studying aboriginal society and therefore part of our history and cultural roots. Natural place names refer, at the time of their creation, to something that characterized the place1, and this information, combined with that provided by other sciences such as archaeology, linguistics, or that found in the chronicles of the Indies and other historical sources, could in some cases contribute to revealing hitherto unknown aspects of the prehispanic cultures of our countries and their development.

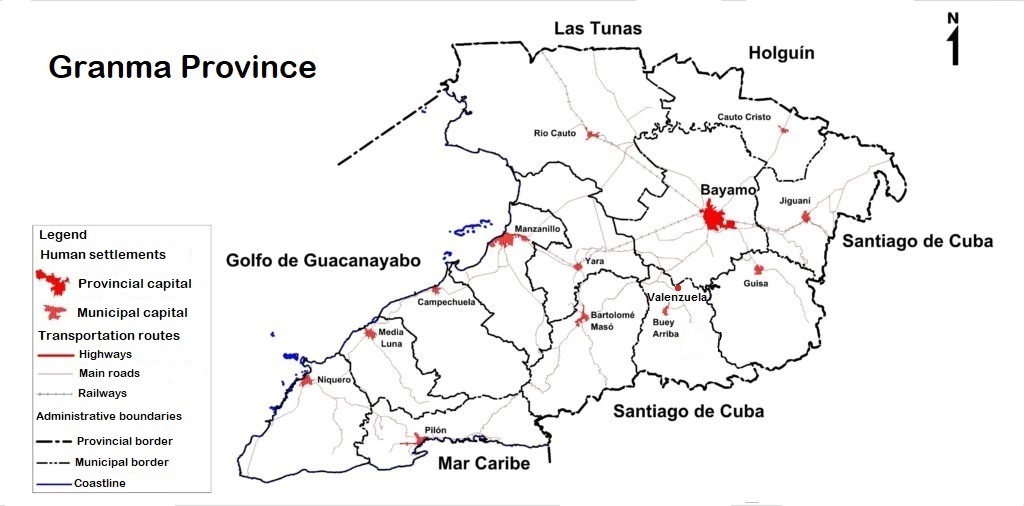

In the present work, we attempt to develop an investigation of this type based on the etymology of the toponym Yao, a locality situated in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra mountain range, belonging to the municipality of Buey Arriba, Granma province, where there is also a village and a river of the same name2. The area was once home to the Yao corral (colonial land grant to establish hog ranch), which depended on the Valenzuela cattle ranch, founded in 1514 by Manuel de Rojas3.

A hamlet in the municipality of Niceto Pérez in the Guantánamo valley and a nearby river are known by a very similar name, Ullao4. The 19th century Cuban geographer and historian Esteban Pichardo points out that the original name of the village and the river is Uyao5.

The aborigines who inhabited Cuba when the Spaniards arrived spoke a language called Taino or Island Arawak, related to another language of the Arawak family, known as Lokono, which is still spoken in some villages in the South American region of the Guianas. The study of the etymology of Island Arawak words is based mainly on the comparative method of linguistics, aimed at identifying lexical and phonetic similarities between related languages, as well as on the limited information recorded by the chroniclers of the Indies on the meaning of some words.

In the structure of Yao and Uyao, the morphemes (u)ya and ao are distinguished. C. H. de Goeje refers the following meanings in lokono of ü-ya (also huia, ia, ueja): ‘spirit’; ‘that by which plants, animals and men differ from dead matter’; ‘something etherical: shadow, image, aroma, etc’6. The ü of ü-ya comes from the German alphabet used by C.H. de Goeje to record the word, is a close front rounded vowel /y/ and is pronounced with the lips in the form of a u but making an i sound.

The Arawak-German dictionary of the Moravian Brothers states: úeja, úejahu, ‘shadow’, ‘image’. ‘spirit’ (schatten, bild, geist)7.

As for the morpheme ao, as we pointed out in a previous work where it is analyzed in greater detail8, in Island Arawak it means ‘space’, as does its cognate lokono (au), documented by C. H. de Goeje9.

Thus, (ü)ya, ‘spirit’ + ao, ‘space’, = (ü)yao, ‘space of the spirit’, where a phoneme /a/ is eliminated by elision.

The question arises: what could have been the motivation for this apparently mysterious place name? The answer is provided by a very important archaeological find made in the mid-19th century. Issue 149 of the newspaper El Faro Industrial, published in Havana on 22 June 1848, records it as follows:

When a slave was digging on the Valenzuela estate belonging to Ledo. D. Manuel Desidero Estrada, the hoe bounced off a stone, and having carefully uncovered its upper part, he was terrified when he noticed that it resembled a human figure, and immediately fled to tell his companions that they were all African-born. When they had assembled they examined it, and as one of them said that it was similar to the images that are placed in churches, they in their ignorance took it for granted that it was a saint, knelt down, and in their own way worshipped the stone, arranging at once to notify the master who was in the city. This master had the stone dug with great care, and they brought it to this city intact, and we have been able to examine it closely. The said stone is a touchstone, of a hardness equal to marble, 14 ½ inches high, and weighs two arrobas and four ounces. It shows a very crudely worked human body, seated on its heels with its hands crossed on its knees touching its base. The contours of the face are quite finished although coarse and without proportion, very large mouth, eyes idem, protruding chin, small and very stocky forehead, the ears confused with the hair that forms a sort of bun, the shoulders very close to the neck, and narrow back10.

This stone figure later became known as the “Bayamo Idol” (Figure 1) and in the 19th century it was included in the archaeological collections of the University of Havana, where it is currently housed in the Montané Museum. Cuban researchers Ramón Dacal and Ernesto Navarro, who carried out a detailed study of the Bayamo Idol, consider that “the Idol can be considered as a manifestation of the Carrier groups of Haiti on the original Meillacoids, which when they moved to Cuba around the 8th century AD gave rise to our early ceramic culture”, although they do not exclude the possibility that it was “made after the arrival of the Taínos in Cuba, that is, after the 14th century”11.

The Valenzuela estate was located in the Yao area. The discovery of the idol in the place known by the aborigines as “spirit space” leads to the conclusion that the sculpture corresponds to an aboriginal cemí (numinous beings and their icons) worshiped in the place, a practice that motivated the name of the locality. This, in turn, allows us to infer that Yao, in a less literal sense, means ‘sanctuary’, ‘temple’.

The dating of the sculpture by experts based on the similarity of the construction technique and its formal characteristics with other works of the Island Arawak agro-pottery culture, the survival of the place name, and the historical circumstances related to the conquest, suggest that this sanctuary remained in operation until the arrival of the Spaniards, when the aborigines buried the idol to protect it.

Figure 1

Bayamo Idol

In order to better understand the Aboriginal conception of the cemíes, it is important to take into account the following observation by Sebastián Robiou Lamarche:

And above all, it must be reiterated that the cemí was not the simple material or symbolic representation of this or that Taíno deity. No. In the figure of the cemí were preserved the spirits of those supernatural beings and cultural heroes who had lived at the time of creation, who now constituted the characters of Taíno mythology transmitted orally from generation to generation through the ceremony of the areíto. In other words, for Taíno animist thought, the cemíes housed the spirits of a mythical past and were therefore worshipped by offering them the first fruits of the harvest13.

Fray Ramón Pané, commissioned by Christopher Columbus to study the religious beliefs of the aborigines, in his An account of the antiquities of the Indians, relates how each cemí belonged to a specific cacique (chieftain)14. The Puerto Rican archaeologist José Oliver is of the opinion that there is a difference between the small, personally owned idols that fulfilled private functions and the larger idols that fulfilled public functions. The latter, rather than belonging to the caciques, were entrusted to them by the community, and were consulted on strategic decisions related to social and economic life: rainfall for planting, good harvest, victory over enemies and fertility of marriage, among others15.

Generally, the places of worship of the cemíes consisted of caneyes (Aboriginal dwelling with circular walls and a cone-shaped roof) and caves separated from the villages, to which, during the celebration of the rites, only the cacique and some nitaínos (local caciques and others members of the elite) were allowed to enter, although the results were later known to the whole community16. The caciques were very zealous in guarding and protecting the cemíes and took measures to prevent them from falling into the hands of other caciques17.

This description of the religious practices of aboriginal agro-pottery communities seems to indicate a local scope of influence of a cemi idol, with repercussions limited to the village of the cacique to whom it is entrusted, which would make it difficult to explain the motivation for the name Yao, since neighboring communities would also have their own idols and shrines, which would make it impossible to distinguish one particular locality from the others.

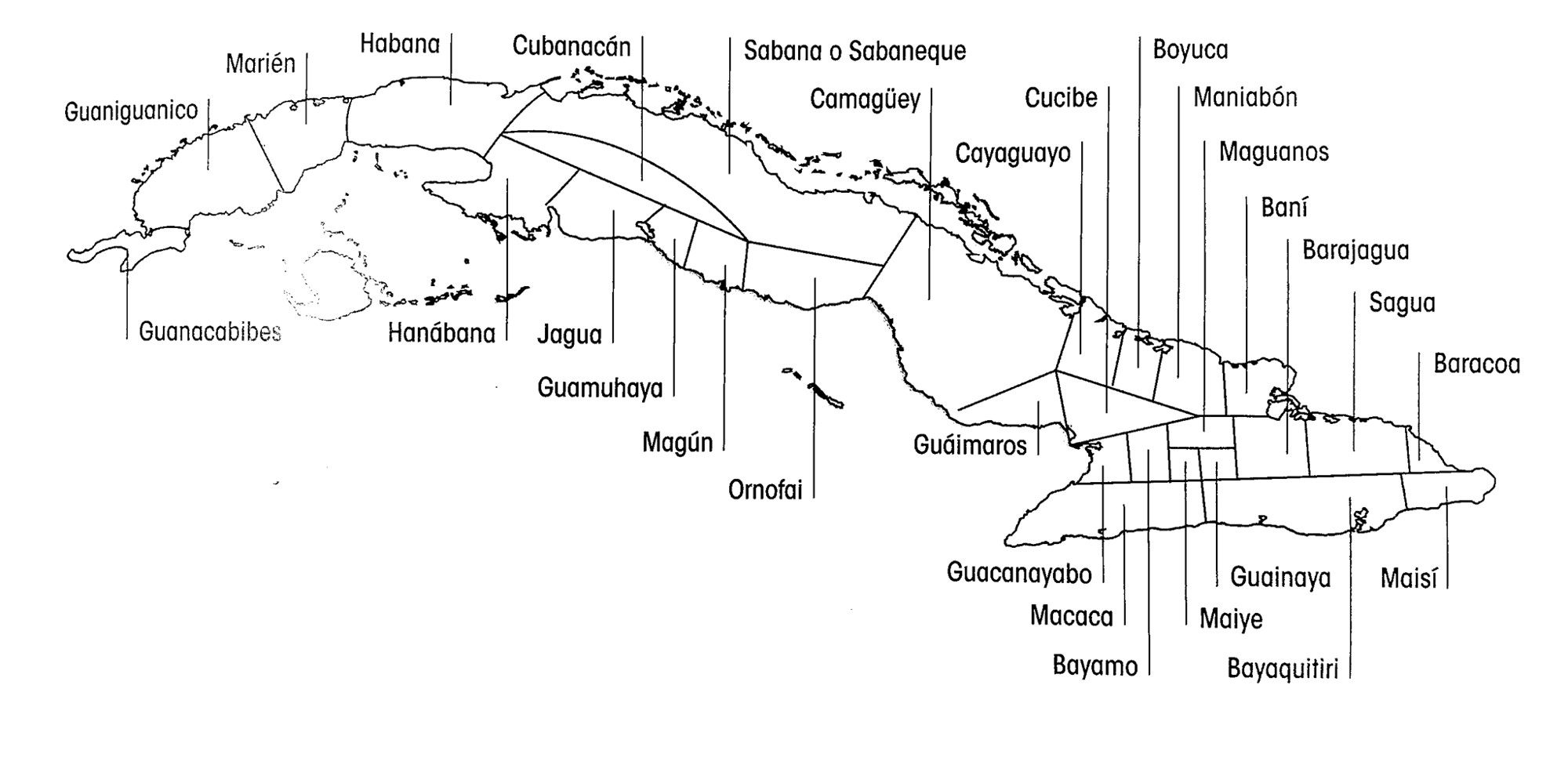

This apparent contradiction disappears if we take into account that the locality of Yao was part of a larger territory, such as the cacicazgos (chiefdoms), where a main cacique exercised authority over the rest. The maps shown in Figures 2 and 3 indicate that Valenzuela estate was close to the limits between several cacicazgos, although we appreciate that it was closer to that of Bayamo and we are inclined to think that it was located in its territory.

The rites dedicated to the Bayamo Idol also involved the main cacique and other nitaínos or local caciques, making the sanctuary a regional religious centre and place of pilgrimage. The influence of the cemí and its oracles extended to the whole cacicazgo. In these circumstances it is very likely that among the main functions of the local cacique or nitaíno of Yao was the care and protection of the cemí and the shrine.

Figure 2

Location of Valenzuela in the Granma Province.

Figure 3

Map of the cacicazgos in Cuba by J. M. de la Torre, modified by Van der Gucht, 1943.

The question arises: Why didn’t the main cacique take possession of the cemí and transfer it to his village? In answering this question, it must be borne in mind that in Cuba the system of cacicazgos did not reach the levels of centralization that existed in Hispaniola, which was highly hierarchical, and was characterized, according to Valcárcel and Peña, by “forms of integration that ranged from family ties and cooperation between autonomous groups to regional orders with levels of political dependence”.19 In such circumstances, taking the idol away from the local Yao cacique could mean the politically inconvenient breaking of an alliance.

Another possible reason for the idol’s permanence in Yao is related to the particularities of the aborigines’ religious beliefs, according to which the cemíes were not indifferent to the place where they were housed. Thus, for example, Pané relates how the behíque (aboriginal priest), after performing the cohoba (religious ceremony) on a tree that has manifested itself as a cemí, asks him if he agrees to come with him and stay in the house that will be built for him. Pané also describes different cases where cemíes leave places where they do not wish to stay, one of which results in the definitive loss of the cemí (Opiyelguobirán) with potentially dire consequences for society20. Considerations of this kind could also explain the location of the shrine in a village on the periphery of the cacicazgo.

On the other hand, it was not possible to replace the Bayamo Idol with a similar one in the village of the main cacique, for reasons that Oliver explains:

… Over the lifetime of the cemí idol, his or her prestige and reputation will grow with the steady accumulation of acts and deeds that can only come with time –the stuff out of which legends and “thick” or long and sedimented biographies are made. Antique, senior cemí idols will be far more reputable, coveted, and valued than newly minted ones (…). Highly prestigious cemí idols cannot be newly sculptured on demand and at the whim of ambitious politicians (caciques, nitaínos); even ordinary people will be aware that such a new icon, even if it were of a high rank and powerful, has yet to demonstrate how effective it is…21.

As for the way in which the Bayamo Idol was found, buried in the vicinity of its temple or sanctuary, it is undoubtedly related to an attempt by the aborigines to prevent its theft or destruction.

The Spanish conquistadors were particularly hostile to Aboriginal religious practices and symbols, which they ruthlessly destroyed. Archaeologist Collin McEwan describes these practices as follows:

Sacred objects of major importance as symbols of the native religion as well as manifestations of occult powers were often precisely the main object of destruction by the Spaniards. Early records and documents indicate that most of them were destroyed without ever becoming part of a wider circuit as “curiosities”. These events in the Caribbean islands (which later became known in the Andes as “the extirpation of idolatries”), caused their native owners to rush to protect and preserve as many objects as possible, which is why they buried or hid them in distant caves. Some survived without ever being found in their hiding places, sometimes for centuries22.

The possible time frame for the burial of the idol is limited and goes from 1510, when the Spaniards, led by Diego Velazquez, began the conquest of Cuba, until 1514, when the Valenzuela cattle ranch was founded and it is unlikely that the sanctuary continued to function.

The two situations that most probably motivated the event are: the repressive action of groups pursuing the cacique Hatuey, originally from the Guahabá region of Haiti, who came to Cuba to escape the Spanish and moved through the territories of several cacicazgos in the eastern region, including Bayamo, where he started a guerrilla war against the invaders and urged the local caciques to fight against them; Likewise, the uprising of the natives against Pánfilo de Narvaez and his men in 1512, when they arrived in Bayamo on a “pacification” plan, followed by the mass flight of the natives to the cacicazgo of Camagüey, events that Bartolomé de Las Casas recounts in detail in his History of the Indies23 .

So far, the cemí corresponding to the Bayamo Idol has remained unidentified. However, there are indications that suggest that it is one of the most important deities in the mythology of the agro-pottery aborigines of the Greater Antilles, about whom Pané wrote: “they believe that he is in the sky and is immortal, and that no one can see him, and that he has a mother, but no beginning, and they call him Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti”24. These indications are:

a) This cemi or its equivalent must also have existed in the religion of the Arawak agro-pottery communities of Cuba, given the religious unity of that culture in the region. In this regard, Las Casas points out:

… the people of this Española, and that of Cuba, and that which we call San Juan, and that of Jamayca, and all the islands of the Lucayos, and commonly in all the others that are in quasi row from near the Mainland, which is said to be Florida, to the point of Paria, which is in the Mainland, beginning from the west to the east, for more than five hundred leagues of sea, and also along the coast of the sea the people of the Mainland, along that shore of Paria, and everything from there down to Veragua, almost all of which was a form of religion….25.

In particular, the eastern region of Cuba where the Bayamo Idol was found, very close to Hispaniola and with no less than seven centuries of presence of the agro-pottery Arawaks at the time of the arrival of the Europeans, must have practiced the same religion, even if there were local particularities, such as assigning a different name to the same cemí. Remember that there was communication and exchange between the Caribbean islands. The insurrection promoted by Hatuey in Cuba is an example.

In eastern Cuba, idols of mythical characters described by Pané, such as Boinayel, Guabancex and Macacoel26, 27, have been identified, suggesting that a principal deity such as Yucahú Bagua Maorocoti must also be present.

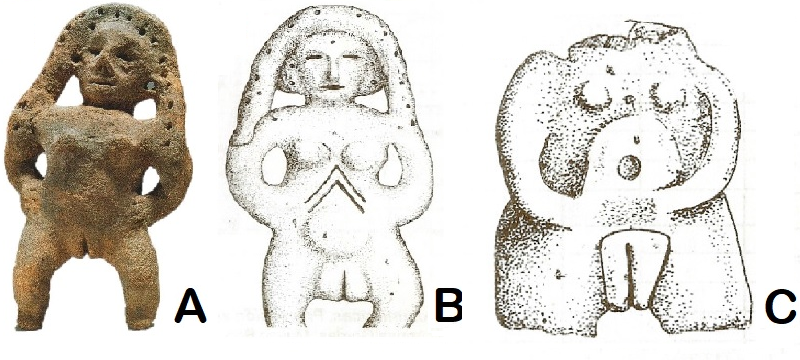

Likewise, José M. Guarch and Alejandro Querejeta, as well as other Cuban authors, have identified idols found in eastern Cuba as Atabeira, mother of Yucahu in Island Arawak mythology28 (Figure 4) which is particularly relevant for this analysis, since the presence of one of the parts of this duality presupposes the existence of the other in the local cult.

Figure 4

Idols identified as Atabeira found in eastern Cuba.

Researchers of the aboriginal legacy and Cuban history, such as José Juan Arrom, Olga Portuondo and María Nelsa Trincado, have pointed to the influence of the Atabeira myth in the formation of the legend and syncretic symbol of the Virgin of Caridad del Cobre, Patron Saint of Cuba30, 31. To the well-known arguments put forward by these prominent intellectuals I would venture to add the following: in the second half of the 20th century, almost 500 years after the arrival of the Spaniards, myths of aboriginal origin were still alive in the eastern region of Cuba, such as those of the Güije or Jigüe, the Mother of Waters and the Cagüeiro, studied by Samuel Feijóo, who classified them as “Cuba’s major myths”. The analysis of the myth of the Cagüeiro reveals its direct relationship with the aboriginal religious conceptions described by Fray Ramón Pané (see entry Cagüeiro, Decoding the Myth on this same site).

This fact shows that four hundred years ago, at the beginning of the 17th century, before the massive arrival in Cuba of immigrants and slaves initiated at the end of the 18th century by the plantation economy, the features of the original aboriginal culture, and in particular those related to religion, had a strong presence in the humble strata that made up the majority of the population, even though their manifestations were repressed, discriminated against and made invisible. In such conditions, religious practices necessarily had to be permeated by ancient beliefs. It is indisputable that the emergence of the symbol of the Virgin of Caridad del Cobre was conditioned by these factors.

b) José Juan Arrom identified Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti in trigonoliths (three-pointed idols) recovered in archaeological finds32 and described by Pané as follows: “The stone cemíes are of various shapes. There are some who say that (…) they have three points, and they believe that they give birth to yucca. They have a root similar to a radish “33.

The trigonoliths are very unevenly distributed spatially in the Caribbean area, which is difficult to explain given the religious unity of the Arawak agro-pottery culture in the region. Marcio Veloz Maggiolo in a 1970 work refers that the “massive” presence of these three-pointed idols has been reported only in Santo Domingo and Puerto Rico, and that reports are almost nil for Cuba, Jamaica, Virgin Islands and Venezuela34. Although some trigonoliths have subsequently been found in Cuba, this does not detract from the validity of the above reasoning.

The only possible explanation is that the Yucahu idols also have a form other than trigonoliths. It is possible to support this hypothesis with other evidence.

Arrom, based on passages from Pané and Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, infers that: “the three-pointed stones were used in agricultural rites of propitiatory character, and that such rites consisted of burying them in the conucos (plots of cultivated land) so that their magical presence would fertilise the crops and multiply the harvests”35. This inference is also supported by the fact that, as Veloz Maggiolo points out, “they appear, in almost all cases, at the surface of the earth, in tilled soils or in old fields without any cultivation”36.

Given the prestige and value that the cemí idols were accumulating and the zeal of the caciques in guarding them, it is unlikely that the most prestigious ones were used in these burials. With the cemí buried, moreover, they could not perform the cohoba ceremony or consult it on important questions that required an answer, as was customary.

That the Yucahu idol was performed the cohoba ceremony and consulted on “strategic decisions related to social and economic life” is beyond doubt. Pané relates the well-known passage where the cacique Cáicihu performed such rites to this cemí, who warned him about the arrival of a “clothed people, who would dominate and kill them, and that they would die of hunger “37.

In the biography of Christopher Columbus written by his son Ferdinand, words of the Admiral are quoted which show that he made a distinction between the cemíes worshiped in the caneyes and the stones used to promote fertility and fecundity. Thus, after describing the practices of the cult of the former, he points out about the latter:

Likewise, most of the Caciques have three stones, to which they and their vassals have great devotion, one is said to be good for the birth of fruits and vegetables. Another for women to give birth without pain. Another so that they can have water and sun when they need it38.

In addition, there are no reports of findings of three-pointed ritual objects made of wood or clay, and there is no reason to suppose that the Yucahu idols could not have been made of these materials, which are frequently used in other cemi icons.

These arguments suggest that the trigonoliths had a form specially designed for the agricultural rites referred to and that another type of representation was possible for the cemíes worshiped in the caneyes. The use of stone in the three-pointed idols is explained by their better preservation in conditions of burial in the plantations.

This does not deny the possibility that some of the larger and more elaborate trigonoliths were worshiped in the caneyes and the cohoba ceremony was performed to them.

Finally, these considerations also indicate that the Bayamo Idol was not buried as part of a religious ceremony and support the hypothesis that the aborigines were trying to make it safe from the Spanish.

c) The Bayamo Idol presents features that symbolize fecundity and fertility, properties that are also inherent to Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti, the spirit of the yucca and responsible for bringing it into being, as Arrom noted from Pané’s work and the etymological analysis of the name39. They are the frog-like body and limbs, and the erect penis, as can be seen in Dacal and Navarro’s description of the Idol:

The work is essentially composed of a very humanized cephalic part, with masculine characters, and another less differentiated but animalistic part, corresponding to the body and extremities of a batrachian, with the possible characteristic of including a representation of the erect male sex40 (see Figure 1).

In order to understand the function of the frog as a symbol of fertility and fecundity, it is necessary to recall the passage related by Pané about the hero Guahayona’s deed. In a very condensed form and omitting aspects that are not essential for our purposes, it can be summarized as follows: Guahayona leaves the Cacibajagua cave in the mountain of Cauta, where the first humans lived. On his journey he takes with him the women, whom he persuaded to leave their children behind, and then leaves the women on the island of Matininó and begins his return to Cauta. For their part, the small children, after calling out to their absent mothers and crying for their breast, are turned into frogs. In this way, says Pané, all the men were left without women. Later, the men get new female companions with the help of Inriri Cahubabayael (the woodpecker), who carves with his beak the female sex into asexual beings that they caught among the trees.

Arrom, decoding Guahayona’s deed, points out that it is aimed at overcoming the practice of incest and considers that the transformation of children into frogs “carries a cosmological meaning related to the rainy season “41. For his part, Oliver notes that: “frogs in Taínoan iconography appear to be suggestive of fecundity and fertility, announcing the rainy season”42.

For our part, we consider the transformation of the children into frogs to be an allegory representing the reversal of the process of fecundity in an offspring of incest, forbidden in the new order initiated by Guahayona. The transformed infants return to the source of fertility and abundance from whence they should never have come. This is direct evidence that the Island Arawak agro-potters regarded the frog as a symbol of fertility.

In the change of direction of the fertility process, the sense of symmetry in the worldview of the Island Arawak agro-pottery peoples is manifested. This is also expressed in various dualities (day and night; living and dead; Fruitful and Inversion cemís), something that was noted by Stevens-Arroyo (quoted by Oliver)43 and which emanates from an intuitive recognition of the dialectical phenomenon of the unity and struggle of opposites.

The trigonoliths from Yucahu also exhibit frog legs. Sebastián Robiou Lamarche points out that “bent legs are a constant in the aforementioned typology of trigonoliths attributed to Yucahu”, and further on he specifies, “… thus, these bent legs or “frogs’ legs” …, we believe, possibly represent a metaphor for rainwater”44.

It is certain that in addition to Yucahu, other cemís propitiated fertility and fecundity, and their idols may also present frog-like features. They seem to correspond to Atabeira, Boinayel and Marohu. In the passage from Christopher Columbus’ biography quoted above about the stones intended to promote fertility and fecundity, one can associate, as Arrom did, Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti with the first one, “good for the birth of fruits and vegetables”; Atabeira, as an ancestral mother, with the second, “so that women give birth without pain”; and the twins Boinayel and Marohu, identified as responsible for rain and sunny weather, respectively, with the third, “to have water and sun when they need it”45.

The characteristics of the idols of these three cemís do not coincide with those of the Bayamo Idol: Atabeira is a woman; the idols of Boinayel are characterized by two furrows running down from their eyes in an allegory of weeping that turns into rain; and Marohu is generally depicted together with his twin.

It is significant that of the characters represented in the petroglyphs of the Caguana Ceremonial Center in Puerto Rico, four are antropozoomorphs with frog-like features on their lower limbs, and they are precisely those whose characteristics could be associated with Atabeira, Yucahu, Marohu and Boinayel (Figure 5). Note the coincidences of the image of the “frog lady” with the idols identified as Atabeira presented in Figure 3.

Figure 5

Petroglyphs from the ceremonial center of Caguana, Puerto Rico, which by their characteristics could be associated with Atabeira, Yucahu, Marohu and Boinayel.

d) In addition to the frog shapes, the Bayamo Idol presents other features very similar to the trigonoliths identified as Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti: the expression of the face, characterized by the raised countenance, the eyes wide open, the mouth also open, as when speaking, and the attitude of concentration of someone who is making an effort to convey an important message (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Comparison of the features and expression of the faces of a trigonolith recognized by Arrom as Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti and the Bayamo Idol.

Note: Image from Arrom, J. J., 1967 47.

Note: Images adapted from Dacal, Ramón and Navarro, Ernesto, 1972 48.

e) The fact that the Yao sanctuary was a regional religious center, as well as the dimensions of the Bayamo Idol, among the largest of the pre-Hispanic stone idols of the Caribbean, suggest a cemí of high rank, beyond the prestige that the idol may have acquired during the time of its existence.

f) Given the rank of Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti in Island Arawak mythology, his icons should be common, which is confirmed by the abundance of male aboriginal figures with frog features that have been found in Cuba. As José M. Guarch and Alejandro Querejeta point out, “frog figures are common in the iconography of the Arawaks of Cuba (…) Because of the frequency with which this occurs (…) it must have had a certain weight in the mythical universe of this people, as well as an irresistible attraction (…)”. Further on they also warn: “the representations of frogs and toads are also related to the Supreme Being Yúcahu Bagua Máorocote by means of a hidden, for us, sign that is only expressed in some cemíes of the Being without Male Ancestor “49.

Of the five aboriginal idols in the museum at Niquero, a locality close to Yao and located in the former territory of the Macaca chiefdom, two are anthropozoomorphic figures with human and frog features (the Idol of Las Coloradas and that of Yuraguana)50. Several of their other characteristics also coincide with those of the Bayamo Idol (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Idols of Las Coloradas and Yuraguana

Note: Images from Domínguez González, Leonel. 2002.

In regard to the expression on the face of the Bayamo Idol and its possible meaning, we should pay attention to the description of the cohoba ceremony by two eyewitnesses to its celebration: Pané and Las Casas:

Pané: … And the lord of them is the first who begins to make the cohoba and plays an instrument; and while he is making the cohoba, none of those in his company speaks until the lord has finished. After he has finished his prayer, he stands for a while with his head down and his arms on his knees; then he raises his head, looking up to heaven, and speaks. Then they all answer him at the same time in a loud voice; and when they have all spoken, they give thanks, and he narrates the vision he has had, drunk with the cohoba that he has sipped through his nose and it has gone up to his head. And he says that he has spoken with the cemí, and that they will gain the victory, or that their enemies will flee, or that there will be great slaughter, or wars, or famine, or other such thing, according as he, who is drunk, says what he remembers. Judge how their brains are, for they say that they seem to see that houses are turned upside down with their foundations up, and that men walk with their feet towards heaven51 (Emphasis added).

Las Casas: I saw them sometimes celebrate their cohoba (…). The first one to start it was the Señor [cacique], and while he was doing it, everyone was silent. When he had taken his cohoba (which is inhaling through the nostrils those powders, as it was said before) and sat down on some low but very well carved stools, which they called duhos (…), his head was turned to one side for a while and his arms were placed on his knees, and then he raised his face to the sky, speaking certain words, which must have been their prayers to the true God, or the one they had for god. They would all then answer almost as we answer Amen, and this they would do with great outcry of voices or sound, and then they would give him thanks, and they were to give him some flattery, capturing his benevolence and begging him to tell what he had seen. He would give them an account of his vision, saying that the Cemí had spoken to him and certified to him of good or bad times, or that there were to be children, or that they were to die, or that they were to have some contention or war with their neighbors…52 (Emphasis added).

It is clear that the expression of the cacique raising his face to the sky, described by Pané and Las Casas, is the same as that of the Bayamo Idol53. He is connected to the cemí through the idol that houses (but does not confine) the disembodied essence of the numen and the words he utters in that position are probably not his own, but those of the spirit speaking through his mouth. Moreover, he also sees the same events that the latter perceives. The reversal of perspective by 180 degrees coincides with Yucahu’s point of view from heaven, where he resides, to earth.

Certainly, the effects of cohoba powders need not be limited to auditory hallucinations and can also provoke visual ones. Note that Pané and Las Casas refer to the cacique’s experience as a “vision”. Once again, the conception of reality is organized symmetrically, this time on the basis of the duality of spirit-cacique and heaven-earth.

The values of the Bayamo Idol as a work of art now stand out more clearly, and the sculptor’s ability to achieve his expressive goals can be appreciated. Full credit must be given to Dacal and Navarro, who were able to appreciate it in this way at an early stage:

The specimen, in short, is a true work of art in which the movement or attitude, the general modelling and the great expression of the face have been achieved with the least number of technical resources, giving, nevertheless, a clear plastic message and, at the same time, a full human-animal symbolic representation was achieved with a sculptural concept that was partly figurative and at the same time stylised54.

These authors also point out that the lack of muscular anatomical details in the entire figure, with the exception of the head and the part of the shoulders, is not an obstacle for the figure to express the plastic message that its author managed to imprint on it55. In this sense, Oliver, commenting on an observation by Jeffrey B. Walker about the ambiguity in Taíno/Chicoid art that manifests itself in the artist’s representation of one or a few parts of the body of an animal or person instead of showing the whole, points out: “the visible cue is what matters to evoke the whole by a process of abduction in the viewer’s mind”56. We believe that this reasoning also applies to the Bayamo Idol.

In relation to the existence in Guantánamo of another place named Ullao or Uyao, it is evident that it corresponded to another aboriginal sanctuary. The fact that it was also located near a river is no coincidence. The preparations for the cohoba ceremony included induced vomiting with a spatula to promote the speed and potency of the effects of the hallucinogenic substances, as well as the cacique’s purifying bath57, so that a requirement for locating the shrines was their proximity to a watercourse.

The Bayamo Idol, in all probability, represented the most spiritually valuable possession of the aborigines who inhabited the cacicazgo of Bayamo. The effort they made to protect it was not in vain, as it remained buried for almost three and a half centuries without being discovered, and has survived safely to the present day. By the time it saw the light of day again, the society it came from no longer existed, but the fusion of its culture with others from Europe and Africa, in a constant process of transculturation, had generated a new people with a new identity, about to begin the struggle for independence. A seed that germinated in the bowels of the homeland and set its sprout in the trunk of Cuban nationality. A symbol that claims its place in our roots.

Notes

- Pocklington, Robert. Introducción a la toponomástica [Introduction to toponomastics]. Fundación Ibn Tufayl. Page 12. www.academia.edu.

- Instituto Cubano de Geodesia y Cartografía. 1978. Atlas de Cuba [Atlas of Cuba]. Pages 138-139. B-5. General geographic map. Scale 1:300 000.

- Enciclopedia colaborativa en la red cubana ECURED. Valenzuela (Buey Arriba). Source: historian Ledesme Garcés Rosales. www.ecured.cu

- Instituto Cubano de Geodesia y Cartografía. 1978. Atlas de Cuba Atlas de Cuba [Atlas of Cuba]. Pages 142-143. C-3. General geographic map. Scale 1:300 000.

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1865. Caminos de la Isla de Cuba. Itinerarios [Roads of the Island of Cuba. Itineraries]. Pages 246-247. Havana. http://books.google.com.

- De Goeje, Claudius Henricus, 1928. The Arawak Language of Guiana. Cambridge University Press. New York. Pages 203-204. www.cambridge.org.

- Moravian Brothers. 1882. Arawakisch-Deutches Wörterbuch, Abschrift eines im Besitze der Herrnhuter Bruder-Unität bei Zittau sich befindlichen-Manuscriptes. In Grammaires et Vocabulaires Roucouyene, Arrouague, Piapoco et D’autre Langues de la Région des Guyanes, par MM. J. Crevaux, P. Sagot, L. Adam. Paris, Maisonneuve et Cie, Libraries-Editeurs. Page 157. https://books.google.com.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2023. Cauto: el río y el nombre [Cauto: the river and the name]. www.laotraraiz.cu.

- De Goeje, Claudius Henricus. Op. Cit. Page 170.

- Dacal, Ramón and Navarro, Ernesto. 1972. El ídolo de Bayamo [Bayamo Idol]. University of Havana. School of Biological Sciences. Montané Anthropological Museum. Page 7.

- Dacal, Ramón y Navarro, Ernesto. Op. Cit. Pages 9-13.

- Dacal, Ramón y Navarro, Ernesto. Op. Cit. Figures 1, 3 y 4.

- Robiou Lamarche, Sebastián. 2013. El rito de la cohoba: la comunicación de los taínos con el más allá [The cohoba rite: Taino communication with the spirits]. Círculo de Investigaciones y Documentación Espiritismo y Cultura (CIDEC). 2do. Encuentro de Diálogos sobre el Espiritismo y la Cultura. Universidad del Este, Carolina, Puerto Rico. https://gotociales.com.

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Relación acerca de las antiguedades de los indios [An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians (A new version with notes, maps and appendices by José Juan Arrom)]. Havana. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

- Oliver, José R. 2009. Caciques and Cemí Idols. The Web Spun by Taíno Rulers between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Pp-77-78. The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa. https://www.researchgate.net.

- Oliver, José R. 2009. Op. Cit. Pages 62, 78.

- Oliver, José R. 2009. Op. Cit. Pages 87-90.

- Moreira de Lima, Lilián J. 2018. “Vida cotidiana y organización social de las comunidades aborígenes de Cuba” [“Everyday life and social organisation in the aboriginal communities of Cuba”]. In Cuba: arqueología y legado histórico. Page 63. Editors: Julio A. Larramendi Joa and Armando Rangel Rivero. Ediciones Polymita. Guatemala City.

- Valcárcel Rojas, Roberto and Peña Obregón, Ángela. 2013. “Las sociedades indígenas en Cuba” [“Indigenous societies in Cuba”.]. In Cardet, José Abreú et al. Historia de Cuba [History of Cuba]. Pages 60-61. Editora Búho, S.R.L. República Dominicana. http://calameo.download/000345214799092124e52.

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Op. Cit.

- Oliver, José R. 2009. Op. Cit. Page 75.

- McEwan Collin. 2008. “Colecciones caribeñas: culturas curiosas y culturas de curiosidades” [“Caribbean collections: curious cultures and cultures of curiosities”]. In El caribe precolombino. Fray Ramón Pané y el universo taíno [The Pre-Columbian Caribbean. Fray Ramón Pané and the Taino universe]. Page 225. Editors: José R. Oliver (main editor), Colin McEwan and Anna Casas Gilberga. Museu Barbier-Mueller d’Art Precolombí, with the collaboration of The British Museum, Ministerio de Cultura, Museo de América and Fundación Caixa Galicia. www://researchgate.net.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. Historia de las Indias [History of the Indies]. Volume 3. Chapters 25 and 26. Biblioteca Ayacucho. Caracas.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. Cit. Page 23.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1909. “Apologética historia de las Indias” [“Apologetic history of the Indies”.]. In Serrano and Sanz. Historiadores de Indias [Historians of the Indies]. Volume I, Page 321. Madrid. http://www.archive.org.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Mitología y artes prehispánicas de las Antillas [Mythology and pre-Hispanic arts of the West Indies]. Editorial Siglo XXI. México.

- Fernández Ortega, Racso y González Tendero, José. 2001. El enigma de los petroglifos aborígenes de Cuba y el Caribe insular [The enigma of the aboriginal petroglyphs of Cuba and the Caribbean islands]. Centre for Research and Development of the Cuban Culture, Juan Marinello. Havana. www.cubaarqueologica.org.

- Guarch Delmonte, José M. and Querejeta Barceló, Alejandro. 1992. Mitología aborigen de Cuba. Deidades y personajes [Aboriginal Mythology of Cuba. Deities and characters]. Publicigraf. Havana. Page 28.

- Roberto Valcárcel Rojas. 2000. “Seres de barro. Un espacio simbólico femenino” [“Beings of clay. A female symbolic space”]. In Caribe arqueológico. 4/2000. Pages 20-34.

- Arrom, José Juan. 2011. “La virgen del Cobre: historia, leyenda y símbolo sincrético” [“The Virgin of El Cobre: history, legend and syncretic symbol”.]. In José Juan Arron y la búsqueda de nuestras raíces [José Juan Arron and the search for our roots]. Editorial Oriente and Fundación García Arévalo. Pages 142-169

- Portuondo Zúñiga, Olga. 2002. La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre: Símbolo de cubanía [The Virgin of Caridad del Cobre: Symbol of Cuban identity]. Agualarga Editores. Madrid.

- Arrom. José Juan. 1967. “El mundo mítico de los taínos: notas sobre el ser supremo” [“The mythical world of the Taino: notes on the supreme being”]. Thesaurus. Volume XXII. No. 3. Pages 378-393. Centro Virtual Cervantes. Instituto Caro y Cuervo. Colombia. https://cervantes.es.

- Veloz Maggiolo, Marcio. 1970. “Los trigonolitos antillanos: aportes para un intento de reclasificación e interpretación” [“The West Indian trigonoliths: contributions to an attempt at reclassification and interpretation”]. In Revista Española de Antropología Americana [Spanish Journal of American Anthropology].Volume 5. Page 318. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/REAA/article/view/REAA7070110317A/25542

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Op. Cit. Page 44.

- Arrom. José Juan. 1967. Op. Cit.

- Veloz Maggiolo, Marcio. 1970. Op. Cit. Page 317.

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Op. Cit. Page 47.

- Colón, Fernando. 1892. “Historia del Almirante Don Cristobal Colón” [“History of Admiral Don Christopher Columbus]. Volume I. Pages 277-280. In Colección de libros raros y curiosos que tratan de América [Collection of rare and curious books about America]. Volume 5. https://books.google.com.

- Arrom. José Juan. 1967. Op. Cit.

- Dacal, Ramón and Navarro, Ernesto. Op. Cit. Page 15.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1995. “Tiempo y espacio en el pensamiento cosmológico taíno” [“Time and space in Taino cosmological thought”.]. In THESAURUS. Volume L. No. 1, 2 and 3. Centro Virtual Cervantes. Page 327. https://cvc.cervantes.es.

- Oliver, José R. 2009. Op. Cit. Page 136.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. El centro ceremonial de Caguana, Puerto Rico. Simbolismo iconografico, cosmovisi6n y el poderio caciquil Taino de Boriquen [The ceremonial centre of Caguana, Puerto Rico. Iconographic symbolism, worldview and the Taino cacique power of Boriquen.]. BAR Publishing, Oxford. Page 110.

- Robiou Lamarche, Sebastián. 2004. “La Gran Serpiente en la mitología taína” [“The Great Serpent in Taino mythology”]. In Gabinete de arqueología [Archaeological office]. Bulletin number 3. Page 55. Office of the Historian of Havana. www.opushabana.cu.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Op. Cit. Page 48.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. Op. Cit. Figures 49, 52, 55 and 56.

- Arrom José Juan. 1967. Op. Cit. Figure I.

- Dacal, Ramón and Navarro, Ernesto. Op. Cit. Figures 5 and 6.

- Guarch Delmonte, José M. and Querejeta Barceló, Alejandro. 1992. Op. Cit. Pages 20-21.

- Domínguez Gonzélez, Leonel. 2002. Ídolos aborígenes de Niquero [Aboriginal idols from Niquero]. Ediciones Bayamo.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. Cit. pages 43-44.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1909. Op. Cit. Volume I. Page 446.

- The researcher Esteban Maciques Sánchez, in his 2018 work, Idolillos colgantes de piedra en la cultura taína (Cuba) [Hanging stone idols in Taino culture (Cuba)], notes the coincidence between the positions of the Taino idol figures and the caciques who performed the cohoba ceremony as described by Las Casas.

- Dacal, Ramón and Navarro, Ernesto. Op. Cit. Page 15.

- Dacal, Ramón and Navarro, Ernesto. Op. Cit. Page 17.

- Oliver, José R. 2009. Op. Cit. Pages 131-132.

- Oliver, José R. 2008. “El universo material y espiritual de los taínos” [“The material and spiritual universe of the Tainos”]. In El caribe precolombino. Fray Ramón Pané y el universo taíno [The Pre-Columbian Caribbean. Fray Ramón Pané and the Taino universe]. Page 176. Editors: José R. Oliver (main editor), Colin McEwan and Anna Casas Gilberga. Museu Barbier-Mueller d’Art Precolombí, with the collaboration of The British Museum, Ministerio de Cultura, Museo de América and Fundación Caixa Galicia. www://researchgate.net.