Despite the wide range of opinions regarding the significance and impact of the 1492 Meeting of Cultures, there is no doubt that it was a momentous event that changed the course of history. This reality gives special geographical and historical significance to the place where initial contact took place: the island of Guanahaní in the Lucayan archipelago, present-day Bahamas. Furthermore, the name is possibly the first aboriginal place name heard and recorded by Europeans on the new continent (in Columbus’s journal), all of which motivate the study of its etymology. The fact that there is still debate about which island Columbus actually landed on, and the possibility of helping to resolve this question through linguistic analysis, reinforces the motivation to address this topic.

The indigenous people who inhabited the Lucayas spoke a language from the South American Arawak family, known as Island Arawak or Taíno, which was also spoken throughout the Greater Antilles. Although there were different variants or dialects, they were mutually intelligible. This is why Christopher Columbus’s Lucayan interpreter was able to communicate with the indigenous populations of Cuba, except the Guanahatabeyes, during the admiral’s second voyage1. The study of the etymology of Island Arawak words is carried out through comparative linguistic analysis with other Arawak languages, particularly Lokono from the Guianas region.

Currently, there is a proposed etymology of the word Guanahani by North American linguists Julian Granberry and Gary S. Vescelius. They considered that Taíno toponyms reflected a vision of space that linked the “east” or “near” and the “west” or “far” by a central geographic locale which was often in coastal locations or in a water passage between islands. They also assumed that these toponyms reflected the direction of movement of the Taíno during their migration through the Antilles, from east to west and from “bottom” to “top”. The procedures used by these researchers also included breaking down the toponyms into their constituent syllables and comparing them with dictionaries and other studies of Arawak languages to determine if a morpheme with the same or similar phonological form and its accompanying semiological denotation could be found2.

In this way, they made the following proposal: wa, ‘land’, ‘place’, ‘country’ + na, ‘small’ + ha, ‘up’ + ní, ‘water’ = Guanahaní, ‘Small Upper Waters Land’3.

Silvia Kouwenberg, a linguist at the University of the West Indies (Mona) in Jamaica, considers Granberry and Vescelius’s attempts at morphological analysis to be often speculative, and this is even more true in the case of his treatment of Taino toponyms4. We are of the same opinion.

First, it’s a mistake to generalize that the toponymic method of Island Arawak follows the direction and other particularities of migratory movement. Island Arawak follows a descriptive naming model, as does Lokono. John Petter Bennett, a native speaker of the latter language, explains this feature as follows:

Some things appear to be called by several different names but this is only because people are fond of calling or identifying some animals or some things according to a peculiar attribute of the subject; it may be because of the song or crowing of a bird, or of the smell or action of an animal. For instance, people call the bigger kind of peccary (bush hog) keheroñ, because of the pronounced animal smell. They call the bird karoba, hanakwa, because of the crowing. The animal known as bushcow, is named kama, in Loko, but they usually call it maiupuri, wich is the Carib name. When you know how to speak Loko, you will be able to tell which is the real name and which is only a nickname of any animal5.

C. H. de Goeje, author of one of the most cited studies on Lokono, also points out this characteristic of that language:

… in Arawak we have a well-developed language, in which there is an inner and essential connection between the idea and the word … an Arawak word is a description of a few salient features of the thing, and the same thing can also be described by mentioning other features belonging to it. And in this way synonyms may come into use, without there being any deviation from the principles of the language6.

Researcher Konrad Rybka, in his work, The Linguistic Encoding of Landscape in Lokono, points out that most place names in Lokono are coined according to the physical characteristics of the environment7.

Island Arawak place names follow this same pattern. It may be that on occasion the characteristic that motivates the name is related to migratory movement, as, for example, in the region of Hispaniola named Caicimú, ‘front of the island’ (cai, ‘island + cimú, ‘front’) but these cases are far from universal, as demonstrated by several studies we published in The Other Root, which analyze the etymology of Island Arawak toponyms. Thus, a place can be named Guanabo because it is a ‘lowland’8; Guanajay, because it is a ‘highland’9; Guane, because its soil is ‘sand’10; Haiti, because it is a ‘mountainous region’11, etc. Furthermore, the highly specific form of the method proposed by Granberry and Vescelius, which includes more than one parameter (east/west, down/up), is even less likely.

Likewise, the meaning that Granberry and Vescelius assign to different morphemes that integrate the structure of toponyms in Island Arawak is usually wrong. We will exemplify this statement during our proposal of etymology of Guanahaní.

In the structure of the word, the following segments are distinguished: guana + ha + ní = Guanahaní.

The first, guana, means ‘land’, ‘place’, ‘earth’, etymology that we analyze in depth in the article Arawak Mysteries in Spanish Spoken in Cuba: Guana, published in The Other Root12. Below we present a summary of the main elements:

Fray Ramón Pané, in charge of Cristobal Colón to study the religious beliefs and practices of the aborigines, who lived several years among them and learned some of his language, wrote that guanara “means a separate place”13. That word is formed by the guana and –ra segments. The second has an identical cognate in Lokono, a demonstrative suffix that denotes a medial distance from which he speaks and indicates the unexpected location of an event14. Thus, guana, ‘place’ + –ra, ‘medial distance from which he speaks’, ‘separate’ = guanara, ‘separate place’.

It is also possible to identify a non-identical cognate of guana in the structure of the lokono words wunabu, ‘(at) the ground’, ‘below’15 and wunapu,‘ (to) the ground’,‘ (fall) to the ground’16.

In other Lokono words that name animals, plants, and mythical beings, the wana form, identical to that of the Island Arawak, has been preserved “fossilized”, such as: wanassuru, ‘trumpet tree (cecropia) and wánnana, ‘a goose’17. The first literally means ‘suck the earth’ (wana, ‘earth’ + ssuru, ‘suck’18 = wanassuru, ‘suck the earth’) and seems to be motivated by the fact that the hollow stems and branches of the species of the genus Cecropia contain a toxic latex. The second is an identical cognate of the Island Arawak word, guanana, and literally means ‘towards other lands’ (wana, ‘land’ + –na, ‘continuation’, ‘plurality’, ‘expected location’19, 20 = guanana, ‘towards other lands’), highlighting the migratory nature of the bird.

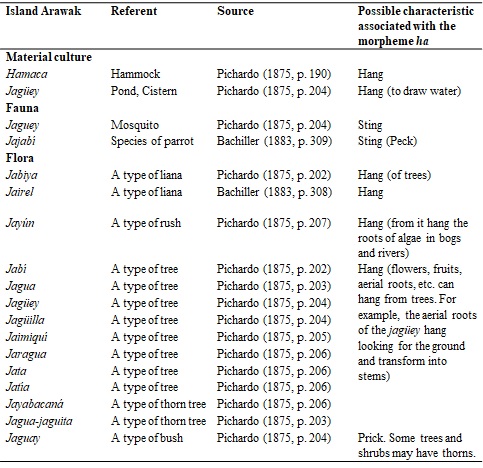

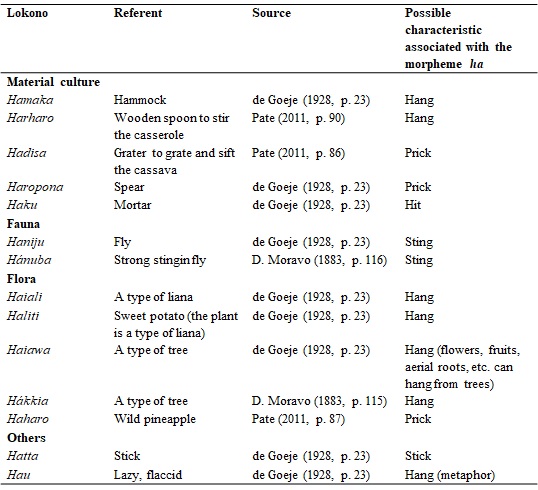

The morpheme ha, as we have explained in other works21, is used to denote the movement of an entity in a certain direction. In the analysis of a sample of 18 Island Arawak words and 14 Lokono words with the root ha in its structure, it was found that in the referents the characteristics of: ‘hang’, ‘sting’, ‘prick’, ‘peck’, ‘stick’, ‘hit’ (see Tables 1 and 2 in the Appendix).

The morpheme ha is also used in Lokono as a suffix of the future with the meaning ‘future certainty’22. Note that the movement towards the future, figuratively, can be conceived as an action that starts from a fixed end in the present to the one free in the future. Likewise, the word Lokono hadali, ‘sun’23, seems to be related to the perception of solar rays as entities with a fixed end in the star and another free beating down on earth.

The last morpheme in the structure of Guanahaní is the suffix –ni, ‘water’, the only one of those in the structure of the word whose meaning is correctly indicated by Granberry and Vescelius. Indeed, the suffix – ni is an abbreviated form of the Island Arawak word guani, ‘water’, not an identical cognate of the Lokono wuini ~ oini, ‘water’24. The word guani and the suffix –ni are present in many place names that designate rivers or coastal places in Cuba: Guanimar, Jiguaní, Caburní, Cabonico, Camajuaní, and Hatibonico, among others.

So, guana, ‘land’ + ha, ‘movement in a certain direction’ + –ni, ‘water’ = guanahaní, ‘water flowing inland’.

As is known from the journal of Christopher Columbus, Guanahaní was characterized by “many waters and a very large lagoon”25. Many islands of the Bahamas have lagoons inside, but the fact that this peculiarity has motivated the aboriginal name “water flowing inland” implies that the size and other characteristics of that body of water must be such that they differentiate that island from the others. The aboriginal name also reveals that these waters came from the sea and were salty.

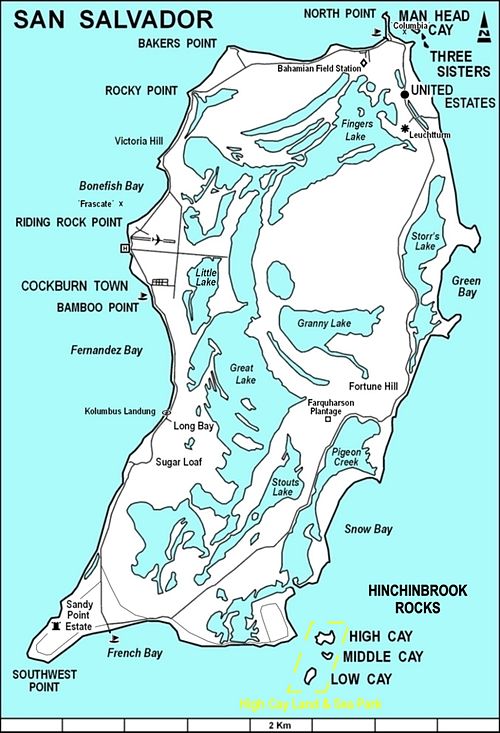

There is an island in the Bahamas with an interior lagoon in its central part that, due to its magnitude and proportion of the surface it occupies, differs from the rest: the current San Salvador, previously named (until 1925) Watling Island. As can be seen in Figure 1, that body of water practically occupies the entire central part of the island. It measures 16 km long from north to south and reaches 3 km in its widest part, and the water of the lagoon is salty26, which coincides with the meaning of Guanahaní in our proposal of etymology.

It is necessary to point out that Bartolomé de las Casas, in a passage in his History of the Indies, refers to Guanahaní and says that “in the middle was a freshwater lagoon they drank”27. We agree with Paulo Emilio Taviani, who points out that Bartolomé de las Casas was never in the Lucayas Islands and that the reference to the fresh water of the lagoon is an arbitrary addition28. It is possible that it has been confused by the fact that there are freshwater sources on the island and the crews were supplied with it. In his journal, Columbus says: “And people, who all came to the beach calling us and giving thanks to God; some brought us water, others, things to eat”29 [the emphasis is ours].

Figure 1

San Salvador Island in Bahamas

Although it is still discussed which island of the Bahamas is Guanahaní, many researchers who have studied the issue believe that it is Watling Island, current San Salvador, based on the coincidence of its characteristics with those described by Columbus, as well as on archaeological findings of European colonial artifacts of the end of the XV century, many of which have their origin in Spain and coincide with the descriptions in the Columbus journal of those exchanged with the aborigines30.

The results of this etymological analysis of the Island Arawak toponym Guanahaní confirm that it is San Salvador.

Appendix

Table 1

Selection of Island Arawak words with the morpheme ha (ja) in their structure, their referents, sources, and possible associated characteristics.

Table 2

Selection of Lokono words with the morpheme ha in their structure, their referents, sources, and possible associated characteristics.

References

- Martyr D’Anghera, Peter. 1892. “Decades of the New World”. First Decade. Book III. Chapter 3. In Fuentes históricas sobre Colón y América. Madrid. https://archive.org.

- Granberry, Julian y Vescelius, Garry S. 2004. Languages of the Pre-Columbian Antilles. Pages 63-77. The University of Alabama Press. Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

- Granberry, Julian y Vescelius, Garry S. 2004. Op.cit.. Pages 80-86.

- Kouwenberg, Silvia. 2010. “Taino´s linguistic affiliation with mainland Arawak”. In Proceedings of the twenty-second congress of the International Association for Caribbean Archaeology (IACA). The Jamaica National Heritage Trust. Page 684.

- Bennett, John Peter. 1995. Twenty-Eigth Lessons in Loko (Arawak). A teaching guide, Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology, Georgetown, Guyana. Page 5.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. The Arawak Languaje of Guiana. Cambridge University Press. Page 236. www.cambridge.org.

- Rybka, Konrad A. 2015. The Linguistic Encoding of Landscape in Lokono. Utrecht. LOT. Page 266.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2023. Guanabo, The Lowland. www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2024. Guanajay, The Upland. www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2025. El Gua aborigen en el español de Cuba. www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2024. Guanajay, The Upland. www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2023. Arawak Mysteries in the Spanish Spoken in Cuba: Guana. www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Pané, Ramón. 1990. Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios [ An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians]. Nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices por José Juan Arrom. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, La Habana. Page 27.

- Rybka, Konrad A. 2015. Op. cit. Pages 63, 98, 145.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. op. cit. Page 111.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. op. cit. Page 111.

- Herrnhuter Bruder. 1882. Arawakisch-Deutches Wörterbuch, Abschrift eines im Besitze der Herrnhuter Bruder-Unität bei Zittau sich befindlichen-Manuscriptes. In Grammaires et Vocabulaires Roucouyene, Arrouague, Piapoco et D’autre Langues de la Région des Guyanes, par MM. J. Crevaux, P. Sagot, L. Adam. Paris, Maisonneuve et Cie, Libraries-Editeurs. http://books.google.com. Página 164.

- Soro ~ ssuru is a root found in Lokono words that denote the ways in which liquid flows are generated, such as: a-soroto, ‘to suck’; a-sorokodo, ‘to be shed’, ‘to well forth’; among others. See C. H. de Goeje, 1928, pages 41, 156-157.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. op. cit. Pages 35, 118-119.

- Rybka, Konrad A. 2015. Op. cit. Pages 63, 98.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2024. Guanajay, The Upland. www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Pet, Willem J. A. 2011. A Grammar Sketch and Lexicon of Arawak (Lokono Dian). SIL e-Books. Página 35.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. op. cit. Page 150.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. op. cit. Pages 35, 167.

- Columbus, Christopher. 1892. “Relación del primer viaje de D. Cristobal Colón para el descubrimiento de las Indias puesta sumariamente por Fray Bartolomé de las Casas”. In Relaciones y cartas de Cristobal Colón. Page 26. Madrid.

- Taviani, Paulo Emilio. 1991. “Why We Are Favorable for the Watling-San Salvador Landfall”. In Proceedings of the first San Salvador Conference, Columbus and his World. Compiled by Donald T. Gerace. Pages 201, 203.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de. Historia de las Indias. Fundación Bilioteca Ayacucho. V. I. Page 204.

- Taviani, Paulo Emilio. 1991. Op. cit. Page 203.

- Columbus, Christopher. 1892. Op. cit. Page 27.

- Blick, Jeffrey P. 2014. “El caso de San Salvador como sitio del desembarco de Colón en 1492. Principios de Arqueología histórica aplicados a las evidencias actuales”. In Cuba ArqueológicaAño VII, núm. 2. Pages 29-49.

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1875. Diccionario provincial casi razonado de vozes y frases cubanas. Cuarta Edición. La Habana.

- Bachiller y Morales, 1883. Antonio. Cuba primitiva. La Habana.

- Herrnhuter Bruder. 1882. Op. cit.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. op. cit.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. La langue arawak de Guyane, Présentation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français-arawak. IRD Éditions. Marseille. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr.