Guacayarima is the aboriginal name for a region located in the southwest of Hispaniola that extends into what is now known as the Tiburón Peninsula (Figure 1). Peter Martyr d’Anghera, in the third of his Decades of the New World, published in 1516, mentions it as one of the five parts into which the aborigines divided the island, which he called “provinces”1, although they did not correspond to any administrative territorial demarcation (like the indigenous chiefdoms) and actually designated geographic regions.

Figure 1

Aboriginal names of the pre-Columbian provinces of Hispaniola, according to the “Decades of the New World” by Peter Martyr d’Anghera.

When explaining the meaning of this aboriginal word, Martyr d’Anghera points out: “…and they call it Guaccayarima because it is the extreme part of the island: the word marima means anus: they call it the ass of the island”2 (extract in Latin from the original in Figure 2).

Figure 2

Extract from the Decades of the New World by Peter Martyr d’Anghera, in the original Latin, on the meaning of the aboriginal toponym Guacayarima.

Peter Martyr d’Anghera never visited the American continent and wrote his Decades based on information passed on to him by people or documents that arrived from those lands. This circumstance has sometimes led to doubts about the meanings he assigns to certain words in the aboriginal language, and even their very existence, as in the well-known case of Quisqueya, the indigenous name for Hispaniola according to the chronicler.

However, the place name Guacayarima has not had the same fate, and the consensus is that it is related to the “rear end” position this region occupies in the geography of Hispaniola, as Martyr d’Anghera pointed out. For example, Jose Juan Arrom, in the lecture given on June 7, 1973, in the Assembly Hall of the Association of Industries of the Dominican Republic, on the inauguration of the Pre-Hispanic Art Room of the García Arévalo Foundation, Inc., states:

And the extensive strip of land that forms the southwestern tip is given the name Gua–cay–arima [by the natives], that is, wa ‘our’, cay ‘island’ and arima ‘butt or rear’. Which, incidentally, would linguistically confirm the route they followed in their explorations: Cay-cimú, ‘front of the island’, to the place where they arrived, and Guacayarima, ‘rear of the island’, to the region they last explored.3

Since we hold a different position, deviating from the meaning suggested by Martyr d’Anghera for this toponym, we will begin by assessing the circumstances surrounding the chronicler and the source from which he received the information, which influenced the etymology they proposed. Subsequently, we will use the linguistic method of comparative analysis to develop a new etymological proposal. This method aims to identify lexical and phonetic similarities between Island Arawak, the language spoken by our Aboriginal peoples, and other languages of the same family, primarily Lokono from the Guianas region. Finally, we will verify whether the characteristics of the geographical feature correspond to and confirm the results obtained, since in Lokono, and presumably in Island Arawak, the meaning of words describes a relevant characteristic of the named referent.

Regarding the credibility of Martyr d’Anghera, perhaps the most qualified authority to give an assessment is Bartolomé de Las Casas, who remained in the American continent from very early on (1502) and had a deep knowledge of the reality of the New World, based on “an enormous amount of first-hand documentation, if not by the historian’s own experience”6. Las Casas considers Martyr d’Anghera to be a “man of authority”7 and that “he deserves more credit than any other who wrote in Latin”8. In particular, he considers his narration of “the first things” related to the voyages of Christopher Columbus to be accurate, since “What he said in them concerning the beginnings was reported by the Admiral himself, the first discoverer, to whom he spoke many times, and by those who were in his company.”9. However, regarding other passages, he notes: “in the other things that pertain to the discourse and progress of these Indies, his Decades contain many falsehoods”10.

From Las Casas’ considerations, we can draw the following conclusions: first, Martyr d’Anghera is an honest chronicler who strives to convey a true picture of the New World. He would not deliberately invent a falsehood. Second, the reliability of his sources is crucial to the accuracy of his statements and is the primary source of his errors or inaccuracies.

It is important to note that Martyr d’Anghera did not uncritically accept the information provided by his sources. As Jens Lüdtke points out, “he interprets and rectifies them based on his humanistic culture,”12 but it is evident that he did not always have the opportunity to carry out such verification. This leads us to focus our attention on the source that provided the information about the toponym Guacayarima and its meaning. Fortunately, we know who that person is. At the beginning of Chapter One of Book VII of his Third Decade, d’Anghera introduces him:

… I received news of the arrival at Court of Andrés Morales. This man, who is a ship’s pilot, familiar with these coasts, came on business. Morales had carefully and attentively explored the land supposed to be a continent, as well as the neighboring islands and the interior of Hispaniola. He was commissioned by the brother Nicolas Ovando, Grand Commander of the order of Alcantara and gobernor of the island, to explore Hispaniola. He was chosen because of his superior knowledge and also because he was better equipped than others to fulfill that mission. He has moreover compiled itineraries and maps, in which everybody who understand the question has confidence. Morales came to see me, as all those who come back from the ocean habitually do. Let us now examine the heretofore-unknown particulars I have learned from him and from several others13.

Andrés Morales was a Spanish navigator and cartographer who was born in 1476 or 1477 and died in 1517. He participated in the third and fourth voyages of Christopher Columbus. In 1501, he joined Rodrigo de Bastidas and Juan de la Cosa on the expedition to Mainland. Between 1505 and 1514, he sailed throughout the Antilles. In 1506, he explored Cuba —without circumnavigating it— by order of the Governor of Hispaniola, Nicolás de Ovando, who in 1508 also commissioned him to explore Hispaniola and draw a map of the island, which he did. He was one of the first to notice the existence of ocean currents in the Atlantic Ocean and to study them.14, 15

Everything seems to indicate that the description of Hispaniola and its toponymy that Andrés Morales conveyed to Martyr d’Anghera is based primarily on the exploration of the island he conducted in 1508. Map-making requires knowledge of local toponymy to identify the various geographical points and to be able to orient yourself on the terrain. Therefore, as part of his cartographic work, Morales must have interacted with the indigenous people to delve deeper into this aspect. Therefore, we believe that the indigenous place names mentioned by Martyr d’Anghera must have actually existed. In fact, many of them, including Guacayarima, are mentioned by other chroniclers. The possible meaning of these place names is another matter. As Las Casas points out, there were practically no Spaniards who knew the indigenous languages:

… because no one, clergyman, friar, or layman, knew any of them perfectly except a sailor from Palos de Moguer, named Cristóbal Rodríguez, the language, and I do not believe that he fully understood the one that he knew, which was the common one, since no one knew it but him. And this fact that no one knew the languages of this Island was not because they were very difficult to learn, but because no ecclesiastical or lay person at that time had any care, small or great, to give doctrine or knowledge of God to these people, but only to make use of them, for which they did not learn more words of the languages, than “give bread”, “go to the mines”, “take out gold”, and those that were necessary for the service and fulfillment of the will of the Spaniards16.

Other evidence suggests that Andrés Morales provided Martyr d’Anghera with erroneous information about the meaning of terms in the aboriginal language. Thus, in the same context of the explanation of the meaning of the word Guacayarima, the chronicler states: “Gua is an article among them, and there are few names, especially those of kings, that do not begin with this article gua, such as Guarionex, Guacanaril, and many place names as well.”17 In reality, the Island Arawak morpheme gua is not an article, as we explained in the entry The Aboriginal Gua in Cuban Spanish, previously published by The Other Root.

Andrés Morales, when communicating with the indigenous people who explained the meaning of the place names to him, most likely used his limited knowledge of the indigenous language and supplemented it with gestures, signs, and mannerisms. This way of exchanging information explains the possible errors in his interpretation of the meaning of some of the place names that he later communicated to Martyr d’Anghera.

Let us now turn to an analysis of José Juan Arrom’s proposed etymology of the word Guacayarima. First, let us examine the claim that the morpheme gua, which appears in the structure of the word, is used as a possessive pronoun with the meaning ‘our’. This is actually one of the many meanings of this morpheme, but, as Konrad Rybka explains in The Linguistic Encoding of Landscape in Lokono, certain types of nouns in that language are never possessed, in particular a number of landscape-related terms, including kairi, ‘island’, have not been attested as the possessed element in possessive phrases18. In Island Arawak, the same thing happens with the non-identical cognate cay(o), which is easy to verify by analyzing other toponyms where this word is included in their structure, such as Cay-cimú, ‘front of the island’, where the possessive pronoun gua does not appear. It is worth noting that the meaning of Caicimú was correctly pointed out in his Decades by Martyr d’Anghera and Andrés Morales (“The beginning of the island in the east is taken by the province called Caizcimú, so named because in their language Cimú means front or beginning” 19).

As for the cay segment of Gua-cay-arima, it does not correspond to the word meaning ‘island’ and is formed by phonemes belonging to two different morphemes, as we will demonstrate later.

Finally, arima does not mean ‘butt’ or ‘rear end’ as suggested by Martyr d’Anghera and reported by Arrom. The word meaning ‘end’ or ‘rear end’ in Lokono is ina or u-ina20, and it also exists in Island Arawak, where it is found, for example, in the toponym Bainoa [ba-in(a)-oa]. In Lokono, the morpheme ina is also part of the words meaning ‘rear’ (iná-sa21, einasa22) and ‘anus’ (d-ena-ko-leroko23, einako24).

Guacayarima is actually composed of two words: guaca and yarima. The former is a well-known Island Arawak word that entered Cuban Spanish with the meaning “underground hole where bananas and other fruits are placed so they ripen more quickly,” according to Esteban Pichardo, who also notes that to have guaca means “to have money buried or hidden”25.

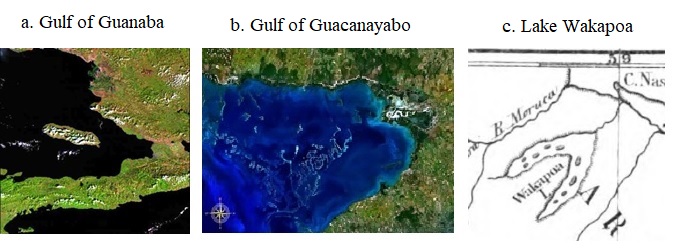

Guaca is composed of the morphemes gua and ca. The former corresponds to the lokono wa, which has numerous meanings, as explained in the entry The morpheme gua in Cuban Spanish. Its general meaning is “separation between events or things that participate in the passage of time”. Its meanings include “contracted” and “curved.” Meanwhile, ca corresponds to the lokono suffix -ka, which is used to indicate that an action has been completed and its effects extend into the present26. Thus, guaca can be used to express that a part of something has been separated, and that entity has been contracted or diminished into a curved shape. This general meaning explains the meaning of “underground hole,” but it can also be applied to a gulf-shaped geographical feature, as is the case of the Gulf of Guanaba, where Guacayarima is located (Figure 2a).

In the south of the eastern region of Cuba, there is a gulf that preserves its aboriginal name, Guacanayabo (Figure 2b). In its structure, the morpheme guaca can be distinguished.

In a region of Guyana traditionally inhabited by Arawaks, there is a lake called Wakapoa (Figure 2c). Its curved shape explains the use of the morpheme waka in the structure of its Lokono name.

Figure 3

Geographic features related to Arawak toponyms that present the morpheme guaca (waka) in their structure.

As for yarima, it corresponds to the Lokono word arama, aruma, which means ‘side’, as C. H. de Goeje points out in his work, The Arawak Language of Guiana27. Konrad Rybka, for his part, transcribes this Lokono word as arima28.

Probably yarima includes the morphemes ya + arima = yarima. In Lokono, ya has a demonstrative function of location29 and in Island Arawak this is presumably also the case.

How can we verify that the Lokono word arima really corresponds to the Island Arawak “yarima“? In Lokono, the names of flora and fauna species often retain “fossilized” forms that must have originated before the separation of the languages. If we can find Lokono species names with the morphemes yarima or arima in their structure, and if these correspond to the meaning of ‘side’, we would have achieved that goal.

Such species names exist in Lokono and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

Names in Lokono of species of flora and fauna with the morpheme yarima or arima in their structure

| Lokono Name | Scientific Name | Description | Source |

| Yarimana | Combretum cacoucia | Creeping plant | John Peter Bennett30 |

| Kaiarima | Maytenus ssp. | Medium-sized tree with buttress roots | D. B. Fanshawe31 |

| Larima | Rhamdia sp. | A type of catfish | D. B. Fanshawe32 |

Yarimana (Figure 3) has inflorescences on long spikes that extend to the sides, a characteristic that gives rise to its name Lokono. The suffix -na indicates ‘continuation’33, so yarima, ‘side’, ‘beside’ + –na, ‘continuation’ = yarimana, ‘extends to the side’.

Figure 4

Yarimana (Combretum cacoucia)

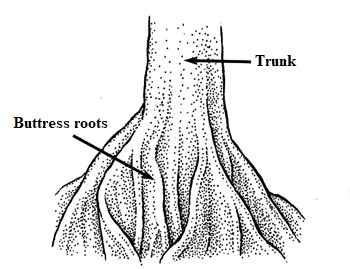

The Kaiarima is a type of tree with buttress roots. These roots extend sideways above the ground (Figure 4), giving rise to its name in Lokono. In that language, ka– is an attributive prefix meaning ‘to have’34, Thus, ka-, “to have” + yarima, “side,” “flank” = kaiarima, ‘with sides’.

Figure 5

Buttress roots

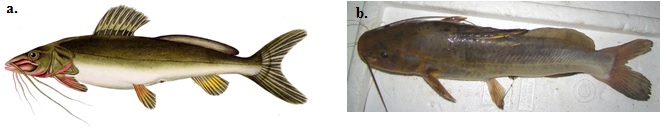

Finally, Larima is a type of catfish that has long whiskers that can extend sideways from a position close to the body(Figure 5), a characteristic that gives rise to its Lokono name. The word’s structure is probably as follows: (a)la, ‘movable’35 + arima, ‘side’, ‘beside’ = larima, ‘moves sideways’.

Figure 6

Larima (Rhamdia sp.)

We are now in a position to propose an etymology for Guacayarima: guaca, ‘gulf’ + yarima, ‘side’ = guacayarima, ‘side of the gulf’. As can be seen, the aboriginal name simply describes the position of the strip of land in relation to the Gulf of Guanaba.

It is evident that Andrés Morales recorded the word without any pronunciation errors, but he misinterpreted its meaning. Five centuries later, we can imagine the exchange of words and gestures between the Spanish cartographer and the aboriginal man trying to explain the relationship between the peninsula’s name and its location within the island’s geography. The resulting misunderstanding left posterity with a labyrinth that obscures the true meaning of the toponym and its motivation. From the present, we attempt to follow the thread that leads out of this maze and contributes to uncovering the true roots of our aboriginal linguistic heritage.

References

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. “Décadas del nuevo mundo” [Decades of the New World]. En Fuentes Históricas sobre Colón y América: Pedro Mártir de Anglería. Traducción y edición por Joaquín Torres Asencio. Madrid. Página 396.

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. Op.cit. Página 397.

- Arrom, Jose Juan. 2011. “Aportaciones lingüísticas al conocimiento de la cosmovisión taína” [“Linguistic contributions to the knowledge of the Taino worldview”]. En Jose Juan Arrom y la búsqueda de nuestras raíces. Fundación García Arévalo y Editorial Oriente. Santo Domingo. Santiago de Cuba. Página 95. Descargado de www.cubaarqueologica.org.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. The Arawak Languaje of Guiana. Cambridge University Press. Página 236. www.cambridge.org.

- Bennett, John Peter. 1989. Twenty-Eight Lessons in Loko (Arawak). A Teaching Guide. Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology. Guyana. Página 5.

- Saint-Lu André. 1986. Prologo a la Historia de las Indias [Prologue to the History of the Indies]. Biblioteca Ayacucho. Caracas.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de. 1986. Historia de las Indias [History of the Indies]. T. I. Página 560. Biblioteca Ayacucho, Caracas.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de. 1986. Op.cit. TI. Página. 560.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de. 1986. Op.cit. TI. Página. 18.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de. 1986. Op.cit. TI. Páginas. 18-19.

- Saint-Lu, André. 1986. Nota 6. Historia de las Indias [Note 6. History of the Indies]. Biblioteca Ayacucho. Caracas. Página 18.

- Lüdtke, Jens. 2007. “Fuentes de la historia de la lengua española: Pedro Mártir de Anglería” [“Sources of the history of the Spanish language: Peter Martyr d’Anghera”]. Página 446. Edición digital a partir de Actas del II Congreso Internacional de Historia de la Lengua Española Tomo II. Madrid. 1992. Biblioteca digital Miguel de Cervantes. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com.

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. Op.cit. Década Tercera. Libro VII. Capítulo Primero. Página 380.

- Fernández de Navarrete, Martín. 1851. Biblioteca marítima española [Spanish Maritime Library]. Madrid. Tomo I. Páginas 88-90. http://books.google.com.

- Sitio web “Todo avante. Historia naval de España” [Website “All Ahead. Naval History of Spain”]. https://todoavante.es/

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1909. “Apologética historia de las Indias” [“Apologetic history of the Indies”]. En Serrano y Sanz. Historiadores de Indias. Madrid. Tomo I. Páginas 320-321. http://www.archive.org/details/historiadoresdei01serr.

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. Op.cit. Página 397.

- Rybka, K. A. (2016). The linguistic encoding of landscape in Lokono. LOT. Utrecht. Páginas 50-51. https://www.researchgate.net.

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. Op.cit. Página 396.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Páginas 35, 119-120.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Página 249.

- Bennett, John Peter. 1995. Twenty-Eight Lessons in Loko (Arawak). A Teaching Guide. Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology. Georgetown, Guyana. Página 33.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Página 249.

- Bennett, John Peter. 1995. Op.cit. Página 33.

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1875. Diccionario provincial casi razonado de vozes y frases cubanas [Almost reasoned provincial dictionary of Cuban words and phrases]. La Habana. Página 166. http://books.google.com.

- Pet, Willem J. A. 2011. A Grammar Sketch and Lexicon of Arawak (Lokono Dian). SIL e-Books. Página 35. https://sil.org.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Páginas 37, 144.

- Rybka, K. A. (2016). Op.cit. Páginas 205-206.

- Rybka, K. A. (2016). Op.cit. Páginas 119, 145, 149-150.

- Bennett, John Peter. 1989. Arawak-English Dictionary. Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology. Guyana. Página 50.

- Fanshawe, D.B. 1949. “Glossary of Arawak Names in Natural History”. En International Journal of American Linguistics, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Jan., 1949), pp. 57-74. The University of Chicago Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1262963.

- Fanshawe, D.B. 1949. Op.cit.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Páginas 35, 118.

- Pet, Willem J. A. 2011. Op.cit. Página 24.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Páginas 237-238.