The study of the mythology of the aborigines who lived in the Greater Antilles at the time of the Spanish conquest faces significant challenges. The only direct source on the subject is the work of friar Ramón Pané, a Catalan religious man from the Hieronymite order, commissioned by Christopher Columbus to “know and understand the beliefs and idolatries of the Indians”1, who learned some of their language and lived among them for several years, during which he wrote An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians, whose original was not preserved and has reached the present through translations and incomplete or partially faithful summaries. Add to that the fact that the Account itself “was already disorderly and confusing”, as noted by José Juan Arrom, a recognized researcher on the subject2.

In 1935, Fernando Ortíz lamented: “What do we know, for example, about the religion of our Indians except the information provided by the Catalan friar Ramón Pane or Pané, and the brief references by Oviedo, Las Casas, Peter Martyr, and Herrera? Do we have a serious interpretation of their mythology?”3 As Arrom points out, the wise Cuban ethnologist’s questions were rhetorical and their answers negative.4

Since the 1970s, new work integrating the results of linguistic, archaeological, and anthropological studies with the information already available from Pané and the chroniclers of the Indies has shed new light on the nature and significance of the religious beliefs of the Antillean aborigines and their relationship to the customs, institutions, and level of socio-economic development of this people. Notable authors who have delved into the subject include José Juan Arrom, Mercedes Lópéz Baralt, José M. Guarch del Monte, Ricardo Alegría, Antonio Stevens Arroyo, Sebastián Robiu Lamarche, and José R. Óliver.

Despite these advances, numerous unresolved questions remain, related to the identity, attributes, and symbolism inherent to figures in the mythology of the aborigines of the Greater Antilles, as well as aspects of religious iconography and the celebration of rituals.

In this work, we propose to delve into one of the mythological characters mentioned by Pané and insufficiently studied: Guabonito, the enigmatic woman who established a relationship with the hero Guahayona, cured him of the “bubo disease” (syphilis) and gave him the cibas and the guanines, symbols that from then on would identify the caciques5.

The passage from the Pané’s Account, where Guabonito is mentioned, is part of the story of the Guahayona’s heroic deed, an allegory of the Neolithic Revolution, characterized by the transition from aboriginal society, made up of relatively isolated groups of fishermen-hunters-gatherers, to a tribal organization. In particular, the narrative symbolically emphasizes the prohibition of incest and the emergence of the figure of the cacique.

A succinct summary of Guahayona’s heroic deed can be outlined as follows: the ancestors of the aborigines lived in two caves named Cacibajagua and Amayaúna, located in the Cauta Mountains in the province of Caonao. One of them, named Guahayona, left with all the women in search of other countries, leaving the children and the rest of the men behind. They arrived at the island of Matininó, where Guahayona left the women and went to another island called Guanín, where he met Guabonito, who cured him of the “bubo disease” and gave him the cibas and guanines, after which he changed his name. Later he returns to Cauta, where abandoned children are turned into frogs and men get new women by transforming asexual beings they found in the trees, with the help of the bird inriri cahubabayael who pierced them with his beak “the place where women’s sex is usually found” 6.

Let us now look more closely at the passage about Guabonito, according to Chapter VI of the Panés Account, in the version of the 16th century translator and editor, Alfonso de Ulloa, retranslated from Italian by José Juan Arrom:

CHAPTER VI

How Guahayona returned to the said Cauta, from where he had taken the women

They say that when Guahayona was in the land to which he had gone, he saw that he had left a woman in the sea, which gave him great pleasure, and at once he sought many lavations to bathe himself because he was full of those sores we call the French disease. She placed him then in a guanara, which means a separate place; and thus while he was there, he recovered from his sores. Afterwards he asked her leave to continue his journey, and she gave it to him. This woman was called Guabonito. And Guahayona changed his name, calling himself henceforth Albeborael Guahayona. And the woman Guabonito gave Albeborael Guahayona many guanines and many cibas so that he would wear them tied to his arms, for in those lands the cibas are made of stones very much like marble, and they wear them tied to their arms and around their necks, and they wear the guanines in their ears, in which they make holes when they are little, and they are made of a metal almost like a florin. It is said that Guabonito, Albeborael Guahayona, and Albeborael’s father were the origin of these guanines. Guahayona stayed in the land with his father, who was called Hiauna. His father called him Hiaguali Guanin, which means son of Hiauna, and henceforth he was called Guanin, and this is his name today. And because they have neither letters nor writing, they do not know how to tell such fables well, nor can I write them well. Therefore, I believe that I put first what ought to be last and the last first. But everything I write, they tell it thus, in the manner I am writing it, and thus I set it down as I have understood it from the people of the country 7.

An initial question that needs to be answered is: in what geographical location of those mentioned in the myth does Guahayona find Guabonito? Although the chapter begins with the announcement of Guahayona’s return to Cauta, the events it recounts occur before that moment, in the region of Guanín Island. We know this for sure because at the end of the previous chapter it is expressly stated that the island was named after what Guahayona took from it when he went there. Pané himself confesses: ” I believe that I put first what ought to be last and the last first”.

Another question that arises concerns the nature and origin of Guabonito. The way in which her encounter with Guahayona is described in Ulloa’s version can lead to confusion: “They say that when Guahayona was in the land to which he had gone, he saw that he had left a woman in the sea”. This wording may suggest that Guabonito was one of the women from Cauta who accompanied Guahayona on the first part of his journey. Fortunately, an excerpt from Pané’s work by the chronicler Peter Martyr D’Anghera informs us of the nature of this mythological character:

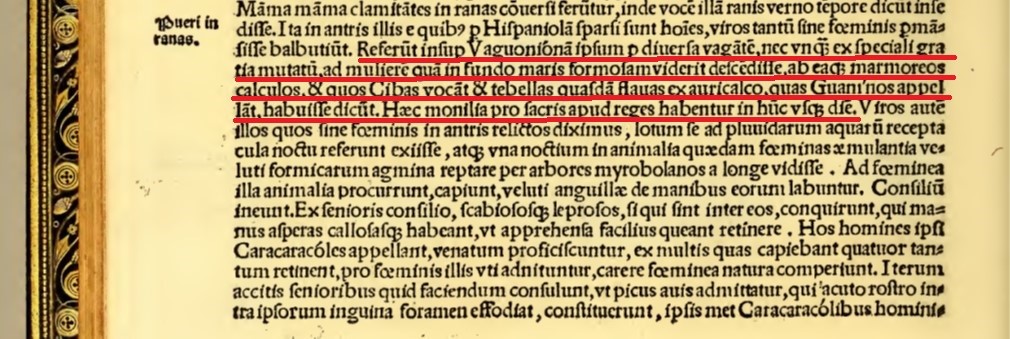

They also say that Vaguoniona [Guahayona] himself, wandering through various parts and never changed by special grace, descended to a beautiful woman he saw at the bottom of the sea, and that from her he obtained some small marble stones called cibas, and certain yellow brass plates called guaninos. These jewels are considered sacred by the Kings to this day8.

The seabed (fundo maris in the Latin of the original by Peter Martyr D’Anghera, see Figure 1), the place where Guabonito resided, leaves no doubt about her nature: she is an aquatic being in the form of a woman, a divinity of the island’s Arawak pantheon. This explains why she was able to cure Guahayona of the “bubo disease ” and why she had the authority to invest him with the symbols of the chiefdom (the cibas and the guanines).

Figure 1

Latin fragment from the Decades of the New World by Peter Martyr D’Anghera which recounts the meeting of Guahayona and Guabonito.

Another characteristic of Guabonito and her bond with Guahayona, is that they had sex. Pané, mentioning the encounter between them, he says; “he saw that he had left a woman in the sea, which gave him great pleasure, and at once he sought many lavations to bathe himself because he was full of those sores we call the French disease”. Everything seems to indicate that she herself transmitted the syphilis, which could be interpreted as a punishment destined to purge the “sin” of the incest and, when that objective has achieved after the time elapsed in the Guanara, cures him. This physical and spiritual rebirth is the one that leads Guahayona to change the name, aware of his new status and the mission that must be fulfilled: to found a new form of social organization where the practice of incest is taboo.

Note as the myth constitutes a legitimation of the figure of the cacique and his authority. After the transformation process ending, Guabonito asks Guahayona for license to continue her way. Even she, a powerful spirit, is also subject to the new authority, faculty that also show the caciques in other myths narrated by Pané, where they even tie the cemíes who want to abandon them (Opiyelguobiran, Baraguabael).

This cleaning and purification process, carried out with the objective of achieving a state or condition that matches the caciques with the divine beings, was a routine part of the preparation of the Cohoba ceremony, in which they communicated with the cemíes, and included actions such as, the fasting for several days, the induced vomit with a spatula and the purifying bath in a river, prior to the consumption of hallucinated substances10.

The fact that Guabonito decided to follow his path alone from the island of Guanín, also seems to confirm her divine and aquatic nature. The physical and daring capacity that reflects the fact of undertaking without company a long sea trip, as well as the disinterest in integrating to a collective, is something unlikely for a human, whose logical reaction would have been to try to stay with Guahayona.

In the mythology of the indigenous peoples of the Guianas region, there is a mythological character that corresponds to Guabonito: they call it Orehu or also Oriyu. Details about this South American myth can be found in the work of four scholars: William Henry Brett, an English missionary who remained around forty years in the British Guiana between 1840 and 1886 11; Walter E. Roth, a British Guiana official between 1906 and 1913 12; and the brothers Frederik Paul Penard and Arthur Philip Penard, who developed ethnographic studies in Surinam between 1896 and 1910 13.

These authors agree that Orehu is a spirit of the waters. Brett always describes it as a woman, although Roth points out that they can also appear in man, as well as in the form of animals, or human part and animal part. This author points out that sometimes they are malignant and in other benefactors. In the first case, they are responsible, together with the Yauhahus (bush-spirits), for diseases, accidents and death; they can cause the shipwreck of vessels and are also causing tsunamis.

His benevolent facet is expressed in granting men and blessings, saving them from dying and in other forms. Among the gifts, there is precisely the remedy for diseases and other evils generated by Yauhahus.

Roth indicates that these beings have “strong sensual inclinations”, “are of love disposition” and seek the “Indians of the opposite sex”.

Brett quotes a mythological passage about Orehu, which presents clear parallels with that of Guabonito. Below we reproduce it, in the version written by José Juan Arrom:

Men lived for a long time without having means to foster this invisible deity [Yauhahu]; They did not know how to avoid their anger or win their good will. In those times the Arawaks did not live in Guiana, but in an island to the north. One day a man named Arawanili walked by the sea, anguished by the ignorance and suffering of his nation. Suddenly the spirit of the waters, the woman named Orehu, emerged from the waves and spoke to him. She show him the mysteries of the cemici, the magical rites that please and control Yauhahu and gave him the maraca, the sacred pumpkin that contains white pebbles that they sound in their spells, and whose sound summons the beings of the invisible world. Arawanili faithfully transmitted to his people everything Orehu told him and thus saved him from his misfortune. When after a life full of wisdom and good works it was time to leave, “he did not die, but ascended”14.

From the foregoing on Guabonito and Orehu we can identify the common characteristics: they are aquatic female spirits; they can induce sick and also cure them, they are prone to sexual relations with men. Likewise, the mythological passages that inspired have obvious similarities: in both cases the aquatic spirits help heroes of the Arawak peoples, contribute to the solution of the problems that afflict their societies and with their help a new era begins in their lives. In addition, they make important gifts that will become religious symbols and the authority of the caciques and the behiques (sorcerers healers).

In the stories of Guahayona and Guabonito, and Arawanili and Orehu, there are some differences: The first hero is searching for a solution to the “sin” of incest, while the second seeks to remedy the suffering and illnesses that afflict his people. In the first case, he receives the attributes of a chief (cibas and guanines) as gifts; in the second, maracas and rituals to control evil spirits. However, both stories can be considered facets of the same feat: the transition from isolated groups of fishermen-hunters-gatherers to tribal social organization and the consolidation of the figures of the cacique and the behique as authorities of the new society.

In a previously published paper (Atabeira, the names of the goddess), we explained how Daniel G. Brinton, a 19th-century American archaeologist, ethnologist, and linguist who was the first to establish the kinship between the Lokono of the Guianas and the language spoken by the aborigines of the Greater Antilles, mistakenly identified the Island Arawak goddess Atabeira with the Orehu of the indigenous peoples of the Guianas, and we detailed the arguments that support the lack of correspondence between these mythological figures.

On that occasion, we also demonstrated through the analysis of the etymology of Atabeira’s names, the information from the chroniclers of the Indies about this goddess and her iconography, that among her attributes was not that of being an aquatic being who controlled the waters, the moon and the tides. It is now evident that such attributes are characteristic of Guabonito, a mythological being distinct from Atabeira, clearly differentiated from each other in Pané’s Account, which offers no indication that they are variants of the same character.

In the version of Pané’s work published by Ulloa, the name Guabonito appears twice in that form and also as Gualonito, as José Juan Arrom points out15. In the versions by Peter Martyr D’Anghera and Bartolomé de Las Casas, the name of this mythological character does not appear. Next, we will propose the etymology of Guabonito, the form of the word that we believe most likely corresponds to the real name of the mythological character.

In the structure of the word two segments can be seen: Guabo + nito = Guabonito.

In Island Carib (a language of Arawak origin with influences from the continental Carib and close to Island Arawak), there is the word nítou, ‘my sister’, according to Father Bretón’s Dictionnaire caraïbe français16. We consider it to be an identical cognate of the Island Arawak word nito. The final u seems to correspond to the pronunciation of the phoneme /o/. John Peter Benett, a native speaker of Lokono, when explaining how to pronounce this phoneme, points out that it is done as in the English word note17. Everything seems to indicate that in Island Carib and Island Arawak this phoneme had the same pronunciation, but the errors of perception of the Spanish motivated the phonological change in the words originating from the latter language.

David Payne, in his work, A classification of Maipuran (Arawakan) languages based on shared lexical retentions, points out the Proto-Arawak form na [thu], ‘sister-in-law’, ‘cousin’18 which bears a certain resemblance to the Island Arawak nito and Island Carib nítou and seems to be related to them to some extent.

In Father Breton’s dictionary, one can also find the expression nitou oüáboutou, “our older sister.”19 The word oüáboutou distinguishes the morphemes oüábou + tou = oüáboutou. The former is found in several expressions included in the aforementioned work, such as noüábou, “in front of me”20.

Breton also indicates that oüábou is the same as oüábara21. This last word coincides with the lokono obura ~ bura ~ bora, ‘before’, ‘in front’22.

An analysis of other expressions that include the morphemes oüábou and oüábara, included in Breton’s dictionaries and grammar of the Island Carib, confirms that their meaning is ‘in front of’, ‘preceding’.

We can now confirm that the morpheme guabo in the structure of Guabonito is a cognate of the Island Carib oüábou.

Thus, in Island Arawak, guabo, ‘precedent’ + nito, ‘sister’ = Guabonito, ‘preceding sister’, ‘older sister’.

The results of the analysis of this character contribute to a better understanding of the mythology of the aborigines of the Greater Antilles.

References

- Pané, Ramón Fray. 1990. Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios (An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians). Nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices de José Juan Arrom. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. La Habana. Page 23.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1990. “Estudio preliminar” (“Preliminary Study”). En Fray Ramón Pané: Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios (An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians). Nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices de José Juan Arrom. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. La Habana. Page 17.

- Ortíz, Fernando. En Arrom, José Juan. 1975, Mitología y artes prehispánicas de las Antillas (Mythology and pre-Hispanic Arts of the Antilles). Siglo XXI editores. Impreso y hecho en México. Page 12. https://archive.org.

- Arrom, Jose Juan. 1975. Mitología y artes prehispánicas de las Antillas (Mythology and pre-Hispanic Arts of the Antilles). Siglo XXI editores. Impreso y hecho en México. Page 12. https://archive.org.

- Pané, Ramón. 1990. Op. cit.

- Pané, Ramón. 1990. Op. cit. Chapters I-VIII, Pages 24-30.

- Pané, Ramón. 1990. Op. cit. Chapter VI, Pages 27-28.

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. “Décadas del nuevo mundo” (“Decades of the New World”). En Fuentes Históricas sobre Colón y América. Libros rarísimos que sacó del olvido, traduciéndolos y dándolos a la luz en 1892, el Dr. D. Joaquín Torres Asensio. Madrid. Clásicos de Historia 525. Page 76. https://archive.org.

- Martyris ab Anglería, Petri. 1530. De Orbe Novo. Compluti apud Michaele de Eguia. Prime decadis. Fol. XX. Collection: jcbindigenous; JohnCarterBrownLibrary; americana. https://archive.org.

- Oliver, Jose R. 2008. “El universo material y espiritual de los taínos” (“The Material and Spiritual Universe of the Tainos”). En El Caribe precolombino: Fray Ramón Pané y el universo taíno (The Pre-Columbian Caribbean: Fray Ramón Pané and the Taíno Universe), edited by J. R. Oliver, C. McEwan, and A. Casas Gilberga. Co-edition Ministerio de Cultura, Museo Barbier-Mueller d’Art Precolombí, y Fundación Caixa Galicia, Barcelona. Page 176.

- Brett, W. H. 1868. The Indian Tribes of Guiana. London. http://books.google.com.

- Roth. Walter E. 1915. An Inquiry into the Animism and Folk-Lore of the Guiana Indians. Global Grey. globalgreyebooks.com.

- Penard F. P. y Penard A. P. 1908. De menschetende aanbidders der zonneslang. H. B. Heyde. Paramaribo. Digitale bibliotheek voor de Nederlands letteren.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Mitología y artes prehispánicas de las Antillas (Mythology and Pre-Hispanic Arts of the Antilles). Siglo XXI editores s.a. Pages 44-45.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1990. Op. cit. Page 63.

- Breton, Raymond. 1999. Dictionnaire caraïbe-français. Ediciones KARTHALA. Page 161. http://www.karthala.com.

- Bennett, John Peter. 1995. Twenty-Eight Lessons in Loko (Arawak). A Teaching Guide. Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology. Georgetown, Guyana. Page 7.

- Payne, David (1991). “A classification of Maipuran (Arawakan) languages based on shared lexical retentions”. In Derbyshire, D. C.; Pullum, G. K. (eds.). Handbook of Amazonian languages. Vol. 3. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Page 418.

- Breton, Raymond. 1999. Op. cit. Page 3.

- Breton, Raymond. 1999. Op. cit. Page 201.

- Breton, Raymond. 1999. Op. cit. Page 40.

- Patte, Marie-France. 2011. La langue Arawak de Guyane. Présentation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français- arawak. IRD Éditions. Marseille. Pages 63, 66, 174.