In an identity born of transculturation, such as the Cuban one, cultural traits are indicators of the human factors that shaped it. Following Fernando Ortiz’s metaphor about the ajiaco (a traditional Cuban stew made with meats, chopped tubers, corn, chili pepper and other vegetables) and its constant cooking of mestizaje (racial and cultural mixing), each one of them would be a kind of characteristic flavour that should allow to identify the type of ingredient that originates it and to judge the proportion in which it has been added to the broth. In doing so, the taster must be able to recognize composition of diverse mixtures, just as the ethnologist must be able to distinguish the different roots of syncretic cultural manifestations.

Mythology is one of the manifestations of cultural identity. In Cuba, it evidences the aboriginal cultural legacy in myths that are among the most widespread on the island: the jigüe or güije, transformed by cultural influences of African origin; the cagüeiro, closer to its pristine aboriginal form, and Madre de aguas (Mother of waters). All three were included among the major myths of Cuba by the outstanding researcher of peasant folklore, Samuel Feijóo, in his classic work “Cuban Mythology”1.

Feijóo describes the cagüeiro as follows: “the cagüeiro has the faculty, when he is pursued in one of his adventures, to become any animal: pig, goat, cow, rabbit, bird…According to legend, the cagüeiro would utter an incantation and become the animal he desired”2. Later he quotes the words of an informant who specifies that the cagüeiro can also become something inanimate, such as trunk of a fallen tree3. Among the characteristics of this mythological being, there are also those of violating the established laws and norms (stealing, robbing, swindling), outwitting the authority that tries to stop him by using his ability to transform and to hide and spend time in the forest, where he feeds by hunting and gathering. In addition, in order to transform he had to wear his shirt inside out4.

It is necessary to specify that Feijóo does not classify the cagüeiro myth as of aboriginal origin and limits himself to labelling it as “myth of the eastern region of Cuba”5. However, several circumstances support the opinion that this myth is an inheritance received from the communitarian society in its agricultural-ceramist stage, existing in the Greater Antilles before the arrival of the Spaniards:

a) The transformation or metamorphosis is present in many myths of the aborigines of the Grater Antilles collected by Fray Ramón Pané, commissioned by Christopher Columbus to study their beliefs and religious practices, who learned some of their language, lived several years among them and is the main primary source on this subject6. Antonio Martínez Fuentes and Julia Leigh Radomski cite among the myths with this characteristics, the conversion of Yahubaba, the opías of Coabay; Baraguabael, the one who always escapes; the resurrection of Baibrama; Mácocael, who had not eyelids; Guanaroca, the loving mother. These authors highlight the resemblance of the cagüeiro with this myths7.

Pane’s description of the cemís [deities or ancestral spirits that may incarnate in created icons and idols, as well as in physical objects and natural phenomena] Opiyelguobirán (Figure 1) and Baraguabael, identifies them as cagüeiros. About the first, he relates:

They say that he has four feet, like a dog’s, and is made of wood, and often at night he leaves the house and goes into the jungle. They went to look for him there, and when they brought him home, they would tie him up with ropes; but he would return to the jungle. And they tell that when the Christians arrived on the island of Hispaniola, this cemí escaped and went into a lagoon; and they followed his tracks, as far as the lagoon, but they never saw him again, nor did they hear anything about him8.

Figure 1

Wooden idol recognized as Opiyelguobirán

Note: Image taken from Arrom, 1989.

About Baraguabael, he points out:

This cemí belongs to a principal cacique of the island of Hispaniola, and is and idol, and they ascribe to him several names and he was found as you will now hear. They say that one day in the past, before the island was discovered, they do not know how long ago, while hunting they found a certain animal after which they ran, and it fled to a ditch; and looking for it they saw a log that seemed alive. Thereupon the hunter, seen this, ran to his lord who was a cacique and father of Guaraionel and told him what he had seen. Then they went there and found the thing as the hunter had said, and they took the log and built a house for it. They say the cemí left that house several times, and went to the place from where he had been brought, not exactly to the same place but near there; for which reason the aforementioned lord or his son Guaraionel sent for him and they found him hidden; and they tied him up again and put him in a sack; and yet, tied as he was, he went away as before. And this is something that ignorant people hold to be very true 9.

b) As we have already pointed out, Indo-Cuban myths are far from being a rarity, particularly in the eastern region which before the conquest concentrated the largest aboriginal population in Cuba. Three of its five provinces currently have the population with the highest proportion of genes of Amerindian origin in the country, and in two of them (Las Tunas and Holguín) nearly 60% come from a Native American female ancestor10.

c) The etymology of the word cagüeiro evidences its origin in the language spoken by our aborigines.

As is well known, the aborigines who inhabited Cuba when the Spaniards arrived were of Arawak origin and spoke a language known as Taino or Island Arawak, related to another language of the Arawak family, known as Lokono, which is still spoken in some villages in the South American region of the Guianas. The study of the etymology of Island Arawak words is based mainly on the comparative method of linguistics, aimed at identifying lexical and phonetic similarities between these related languages, as well as on the limited information recorded by Chroniclers of the Indies on the meaning of the words.

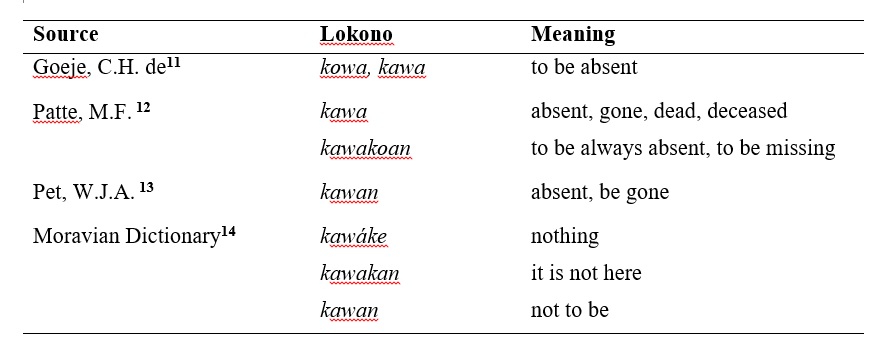

In the structure of the name of the cagüeiro, the union of the Island Arawak words -modified-, cagua and erí, can be distinguished. The first is a cognate (word with the same etymological origin) of the Lokono kawa, with the meaning of ‘absence, disappearance’, as can be seen in Table 1, where sources documenting the ancient and modern Lokono are cited.

Table 1

Meanings of kawa and derived words according to various sources documenting Lokono

Regarding erí, it can be found in the structure of several Island Arawak words that chroniclers recorded, such as, eyerí, matunherí, baharí, guaxerí. It can also be identified in a toponym such as caujerí.

In the case of the word eyerí, Cuban researcher and linguist Sergio Valdés Bernal, quoting M. Álvarez, and I. Rouse and B. Waters, notes: “the ethnic denomination igneri appears documented for the first time in 1516, in the Decades of the New World by Peter Martyr D’Anghera, although later the forms iñeri, eyeri, ieri were generalized, coming from the Island Arawak ierí, ‘human being”15.

For their part, matunherí, baharí, guaxerí, are titles to express the dignity or status of people, as shown in the work of José Juan Arrom, For the History of the Words “Conuco” and “Guajiro” 16.

In Lokono there is the word o-io-ci, documented by C. H. de Goeje with the meaning of ‘friend, neighbour, kindred, people’. This author also notes that “presumably it is connected with oyo, iyu, ‘mother’17. Indeed, ancient Arawak society was subdivided into matrilineal families and clans, where “a child is considered to belong to its mother’s clan, and a man who marries becomes subject to his father in law” 18. We consider this word to be a non-identical cognate of the Island Arawak eyerí, where the first morpheme ey also comes from oyo, iyu with the meaning ‘of the family’, ‘of the lineage’, ‘of the tribe’, while the morpheme erí is the bearer of the meaning ‘human being’.

Thus, ey, ‘of the family’, ‘of the lineage’, ‘of the tribe’ + erí, ‘human being’ = eyerí, ‘human being of the family’, ‘human being of the lineage’, ‘human being of the tribe’, which explains its use as an ethnonym. Also, ‘of the lineage of human beings’, ‘of the class of human beings’, to refer in general to the condition of being human.

Likewise, cagua, ‘absence’, ‘disappearance’ + erí, ‘human being’ = caguaerí, ‘human being that disappears’, describing the attribute that define the cagüeiro, for when it transforms its pursuers lose track of it.

Now, how did the Island Arawak word caguaerí become cagüeiro when it entered the Spanish spoken in Cuba? Let’s try to trace this transformation:

a) The rules of phonetic evolution from Latin to Spanish include a case called “monophthongization”, which establishes, among other guidelines, that the diphthong -AE becomes –E, except when it is accented in Latin, when the results is –IE, for example: AEDIFICARE > “EDIFICAR”; DAEMONIUM > “DEMONIO”; CAELUM > “CIELO”. A similar process seems to have taken place when cagüeiro was incorporated into popular Cuban speech.

b) The ending erí is rare in Spanish, there are very few nouns that presents it and these are basically newly created (referí, azerí). Popular language replaced the last two phonemes by the ending iro which contains them and is common in the language (suspiro, retiro, papiro, zafiro, Ramiro). A similar process was experienced by guaxerí when it became guajiro.

In this way, caguaerí became cagüeiro. It is interesting to note that toponyms are more resistant to this type of transformations; thus the name of the locality of Caujerí, in the present province of Guantánamo, preserved the Island Arawak morpheme in its ending.

To delve deeper into the relationship of the cagüeiro with aboriginal mythology, we must answer the question: how do cagüeiros acquire their special powers? Mythology must offer some clue to answer the question and in that sense we will turn our attention to the opías (spirit of the dead).

Fray Ramón Pané and his An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians, is the main source of information on Taino mythology. In chapter XIII, entitled “Of the form that the dead are said to have”, he refers:

They say that during the day they are secluded, and at night they go out to walk, and that they eat a certain fruit, which is called guava, which has the flavour of [quince] that during the day are … And at night they became fruit, and that they feast, and go together with the living. And to know them they observe this rule: that with their hand they touch their belly, and if they do not find their navel, they say that is operito, which means dead: that is why they say that the dead have no navel. And so they are sometimes deceived, that they do not notice this, and they lie with some woman of Coaybay, and when they think they have them in their arms, they have nothing, because they disappear in an instant. They believe this to this day. When the person is alive, they call the spirit goeíza, and after death, they call it opía; which goeíza they say appears to them many times in the form of both man and woman, and they say that there has been a man wanted to fight with her, and that, coming to the hands, she disappeared, and that the man put his arms elsewhere on some trees, from which he remained hanging. And this is generally believed by all, both young and old; and that it appears to them in the form of father, mother, brother, or relatives, and in other forms. The fruit of which they say the dead eat is the size of a quince. And the aforementioned dead do not appear to them during day, but always at night; and for this reason it is with great fear that some dare to walk alone at night19.

From this excerpt we can conclude:

a) The opías can transform into anything and disappear just like cagüeiros.

b) The opías also share other characteristics with the cagüeiros, such as violating social norms and make fun of people.

c) The living can have sexual relations with the opías.

The agro-pottery peoples who populated the Greater Antilles at the arrival of the Spaniards conceived death as a continuation of physical life in another realm, which was noticed by Christopher Columbus, who, in the notes transcribed by his son, Hernando Columbus, when commenting on this vision of death, says: “They go to a certain valley, where each main cacique [tribal chieftain] believes his land to be, affirming that they found there their fathers and all their ancestors, who eat, have women, and many pleasures and joys…”20.

This belief explains the mass suicides in rebellion against the oppression of the conquerors. This practice reached such an extent that the ruthless encomendero [colonist granted control of land and Indians to work for him] Vasco Porcallo de Figueroa, as the only effective way to prevent it, ordered to cutting of the virile member and testicles of men who tried it21. The fear of continuing existence after death with an incomplete and dysfunctional body achieved the desired effect for the torturer22. All of this suggests that they also believed that the spirits of the dead retained the potential to impregnate.

Another evidence that the spirits of aboriginal mythology could procreate with human beings is the story contained in a passage of the An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians, about the cemí Corocote, who cohabited with the women of the caciques in whose house he was. About this cemí Pané refers: “And they also say that two crowns were born on his head, so they use to say: Since he has two crowns, he is certainly son of Corocote” 23.

In short, probably in aboriginal mythology the cagüeiros were the result of the carnal union of the opías with the living, and their extraordinary powers of transformation are an inheritance from their progenitor spirits.

This conclusion is also directly confirmed by the etymology of the name of the cemí Opiyelguobirán. The word opía, as Pané explicitly states in chapter XIII of his work, means ‘spirit of the dead’ (“while the person is alive, they call the spirit goeíza, and after death, they call it opía”) and he also expressly states in chapter IX that the suffix –el means “son of” (“there was a man named Yaya […] and his son was called Yayael, which means son of Yaya”) 24. Later, in his Account of Antiquities, Pané mentions another name with the suffix –el and also clarifies that it is the son of another character (“…whose province was called Macorís, and the lord of it was called Guanáoboconel, which means son of Guanáobocon”) 25.

Thus, the common attributes with the cagüeiro of Opiyelguobirán are explained by his condition of “son of the spirit of the dead”, as the first part of his name reveals26. In fact, Opiyelguobirán can be considered a cemí representing the cagüeiros.

As is well known, the agro-pottery peoples of the Greater Antilles were organized in communitarian societies that in their most complex form reached the category of cacicazgos (chiefdoms), with a social structure composed of caciques, nitaínos (nobles) and naborías (common people), embryonic manifestations of the social classes, where the former organized work and the distribution of goods, and directed other main activities of the community. Decisions made were followed without discussion and the directions given were strictly adhered to; accepted moral standards were observed and crime and fighting were practically non-existent. Theft was an extraordinary act, strongly repudiated and punishable by death. Father Las Casas relates: “It was not known what was theft, nor adultery, nor force that man should do to any woman, nor any other vileness, nor that one should speak any insult to another by word”27.

The existence of a mythological character such as the cagüeiro or cemí Opiyelguobirán, with a clearly antisocial facet that resists authority and seems to be the antithesis of the usual behaviour of the agro-pottery aborigine of the Greater Antilles, is striking. To understand this fact, it is necessary to pay attention to the level of development of that society.

Despite de racist opinion rooted for centuries in Cuban society by colonialism, which identifies everything aboriginal with technical and cultural backwardness, the reality is that, as Lilian Moreira de Lima points out: “The farming communities of Cuba had an efficient and specialized productive system to meet the vital needs of the community” 28.

They had an agriculture with diverse cultivation techniques (montones -artificial mounds of topsoil-, slash and burn, irrigation ditches, terraces, among other) with yields that guaranteed a productive surplus. Fishing and hunting techniques were also varied, the former including traps, nets and corrals. They built villages that reached a population of up to three thousand people and manufactured large canoes and other types of small boats (cayucos), as well as tools of different types; they spun and wove cotton; their artisans manufactured various ceramic products and made other works of art using different materials. In addition, they practice barter trade on a local and regional scale (among the Caribbean islands).

Although they were very frugal in their diet, they consumed a varied and nutritious food. Agricultural products included cassava, corn, beans, peanuts, chili peppers, sweet potatoes, guagüí or white malanga [Colocasia esculenta] and other types of tubers. They consumed fruits such as guava, pineapple, mammee apple, soursop, annona and caimito [Chrysophyllum cainito], among others. Sources of animal protein included sea and river fish (of numerous species), manatees, chelonians (loggerheads, hawksbills and jicoteas [Trachemys decussata], as well as their eggs), molluscs (queen conchs [Strombus giga], ciguas [Cittarium pica], oysters, among other), jutias [edible Caribbean rodents], iguanas, majás [non-poisonous boas], crabs, frogs and a variety of native and migratory birds.

Speaking about Cuba, Father Las Casas testifies: “There were, as I said, very abundant in food and all the things necessary for life; they had their farms, many and very tidy. We are ocular witnesses that they had everything to spare and that we have killed hunger with it”29.

The descriptions of Christopher Columbus30 and Father Las Casas31, on the physical appearance of the aborigines, portray well-fed people, with no signs of malnutrition.

Conflicts between villages or cacicazgos were rare and were generally resolved by peaceful means. With the exception of the sporadic incursions of the warrior tribes of the Caribs in some areas of the Greater Antilles, they lived in peace and in balance with nature.

In terms of spiritual life, they practiced their religion centered on the worship of the cemís; they celebrated areítos with ritual dances and chants, and a popular pastime was the playing of ball. Craftsmen, in addition to tools and other goods, produced works of art in the form of liturgical and utilitarian objects; they used dyes to decorate the body, as well as pieces of jewellery and ornaments. The true story of “the faithful death”, as José Martí32 poetically describes it, of Guanahatabenequena, the beautiful wife of the cacique Behequio, who adorned herself with her favourite necklaces and ornaments before being buried alive next to her husband, has reached our days.

The distribution of time between the different activities guaranteed rest and participation in cultural, sports and recreational events. Father Las Casas describes a typical day as follows: in the morning they had breakfast and went to work in the fields, fishing, hunting and another tasks; at noon, they had lunch, and the rest of the day they danced, sang and played ball; at night they had dinner33.

In short, the social organization guaranteed material and spiritual security within the framework of the technological development they possessed. In this society, compliance with the rules, as well as with the orientations of the caciques and nitaínos was essential for the organization and development of the main economics activities, which required specialization and coordinate work on higher scale compared to more primitive forms social economic development. The alternative was a return to the hunting-gathering hordes, characterized by small human groups living in relative isolation and faced a much more insecure and haphazard existence.

In this sense, the man of the agro-pottery communitarian society of the Greater Antilles sacrificed his individuality to the collective interest, a renunciation that was codified in the moral and norms of that society. The individual, in the vast majority of decisions, had no right of choice and had to subordinate himself to the group. Engels explains it as follow:

The tribe, the gens, and their institutions were sacred and inviolable, a higher power established by nature, to which the individual subjected himself unconditionally in feeling, thought, and action. However impressive the people of this epoch appear to us, they are completely undifferentiated from one another; as Marx says, they are still attached to the navel string of primitive community34.

This analysis allows us to understand why their religious ideas conceived life after death in the way they did: the opías did not need to work to subsist and were free from the moral and social ties that put a brake on individuality. They spent their time in parties, jokes and pleasures, in which they manifested irreverent behaviour without any restraint.

The cagüeiros and cemí Opiyelguobirán who represents them, were in between these two worlds: part of the time they were integrated into society and at other times they lived outside of it. Opiyelguobirán, at night, “left home and went to the jungles”, where he did not need to comply with social norms. In the stories collected by Samuel Feijóo in eastern Cuba, the cagüeiros could also spend long periods in the forest and managed to subsist by hunting and gathering.

It is now understood why Opiyelguobirán is represented with dog paws, the only domestic animal that the aborigines possessed, since de parrots, other small birds and jutías that they kept in captivity cannot be considered as such. In the dog they saw a species that sacrifices its freedom for the sake of reaching security with men, but that keeps its wild nature latent and in fact can also live in that state.

Researchers Racso Fernández Ortega and Juan Cuza Huart have also pointed out the dual nature of Opiyelguobirán which oscillates “between the worlds of culture and the wild or primitive” and its relationship with the condition of dogs between the wild and domesticate state35.

The first to suggest the mediating role of Opiyelguobirán was José Juan Arrom, who in his work Mythology and pre-Hispanic arts in the Antilles, refers:

…One wonders if when he went into the jungles at night, it was to guide the spirits of the recently deceased on their uncertain journey to Coaybay. Or if, when they returned to participate in their amusing nocturnal adventures, it would be to warn them, with howls inaudible to the living, to return before dawn to their distant valley –lest the sun find them on their way and turn them into jobos [trees, Spondias mombin]36.

This idea was developed by Puerto Rican researcher José R. Oliver, who points out:

He has the obligation [Opiyelguobirán] to maintain living and non-living beings in the world that is appropriate to it. Controlling –so to speak- what enters and leaves from one domain to another. This is a mediating character that marks the separation and, at the same time, maintains the balance between both worlds by regulating the transit of the spirits in the appropriate time (night versus day) 37.

It is difficult to determine to what extent the details of Arrom and Oliver’s interpretation of Opiyelguobirán correspond to the reality of aboriginal mythology; however, there is no doubt that its essence is correct, which lies in the mediating role he play between the world of the dead and the world of the living, given his dual nature. The same can be said about the cagüeiro.

On a deeper symbolic level, the mediating or balancing function of Opiyelguobirán and the cagüeiros is aimed at maintaining the balance between compliance with social norms and individual freedom. They were arbiters of the exercise of “higher power established by nature” that sacrificed individuality in exchange for material and spiritual security; they were a permanent reminder of the need for obedience and preservation of the social order, as well as of the dire consequences of its violation, but also of the right to rebel when its premises were not satisfied and the tribal organization failed to fulfil its mission.

In the aboriginal agro-pottery society of the Greater Antilles, the perception of stability and prosperity of the community was closely linked to the figure of the cacique and his performance. For that reason, as Oliver points out38, he fought to keep Opiyelguobirán in the assigned house and even tied him to that objective, since his permanence meant the approval of the cacique’s performance and legitimized the authority he exercise; while his escape was a verdict of failure and a threat to the leader’s prestige and influence.

In our opinion, the escape to primitiveness was not always associated with the inefficacy of the cacique. In certain situations, when the very existence of the community was threatened, it was an acceptable strategy used to avoid danger and preserve the lives of its members. For this reason, the first reaction of the Cuban aborigines to the arrival of Christopher Columbus and his companions in 1942 was to abandon their village and hide in the forest.

However, they were also capable of showing great courage. During the Spanish conquest, once it was demonstrated that peaceful coexistence with the invaders was impossible, they fought with bravery and, as the enemy surpassed them in the quality of weaponry, they use guerrilla tactics. Among the numerous events of rebellion and armed struggle that took place were the insurrection maintained for ten years by the cacique Guamá and his men in Cuba; the uprising of the cacique Enriquillo in Hispaniola, which lasted for thirteen years and forced the Spanish crown to make pact; and the rebellion of 1511 in Puerto Rico, led by the cacique Agueybaná, which also lasted for years and involved a significant percentage of the indigenous population of the island39.

In his Account of the Antiquities of the Indians, Pané concludes his story about Opiyelguobirán by saying that when the conquerors arrived in Hispaniola, he escaped, went to a lagoon and was never seen again. This is a clear indication of the refusal to be subjugated and the decision to preserve freedom once discipline and compliance with rules are not socially justified. In this case, the rebellion is mainly against the order implanted by the Spaniards, although the cemí moves away from the cacique who can no longer guarantee the normal functioning of the tribe.

The abridged version of Pané’s work included by Peter Martyr D’Anghera in his “Decades of the New World”, provides information – not found in other transcriptions – on the impact of the disappearance of Opiyelguobirán on aboriginal society: “was considered a sinister forecast of the misfortunes of the country”40. We can now understand this reaction: the loss of the cemí threatened the very foundations of the established social order and ushered in a period of uncertainty about the future. It was the reflection in aboriginal spirituality of the events triggered by the European conquest.

During the years of struggle in the jungle against the conquerors, the myth of the cagüeiro must have taken on new aspects as a symbol of resistance and rebellion, as it did during the later period, when many natives went into the most remote mountains and forests to avoid contact with the invaders. This could explain why this myth has remained alive over the centuries in eastern Cuba.

Over the years, some features of the cagüeiro changed: from mockery inherited from the opías, he shifted to robbery, steal and swindle; the aborigines did not use shirt, but the fact that the cagüeiro, in his modern variant, had to put it on backwards to transform himself, is a way of indicating the transition of his dual nature from collectivism to individualism; if before he escaped from the conquerors, now he escapes from the new representatives of authority, which in the peasant environment of Cuba before 1959, to which the stories collected by Feijóo correspond, was mainly the Rural Guard.

To attempt a final evaluation of the findings of this research on the cagüeiro myth, we can repeat with Lévi-Strauss: “…Myths teach us a lot about the societies from which they originate, they help to expose the intimate keys to their functioning, and they clarify the raison d’être of beliefs, customs and institutions whose plan seemed incomprehensible at first glance…”41. In the process of decoding it, we have learned about the subjectivity of our aborigines and can now understand them better, which ultimately can contribute to know ourselves better, because although we are not them, in some way they are still part of us, of our genetic code and of our culture.

Notas

- Feijóo, Samuel. 1986. Mitología cubana [Cuban Mythology]. Editorial Letras Cubanas. Havana.

- Feijóo, Samuel. Op. cit.. Page 221.

- Feijóo, Samuel. Op. cit.. Page 222.

- Feijóo, Samuel. Op. cit.. Page 221.

- Feijóo, Samuel. Op. cit.. Pages 221-225.

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Relación acerca de las antiguedades de los indios (nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices de José Juan Arrom) [An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians (A new version with notes, maps and appendices by José Juan Arrom)]. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

- Martínez Fuentes, Antonio and Leigh Radomski, Julia. 2013. El pueblo originario de Cuba: ¿un legado olvidado o ignorado? [The Original People of Cuba: a Forgotten or Ignored Legacy?]. In Espacio Laical/3/2013. Page 76.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. cit. Page 46.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. cit. Page 48.

- Marcheco-Teruel B, Parra EJ, Fuentes-Smith E, Salas A, Buttenschøn HN, et al. 2014. Cuba: Exploring the History of Admixture and the Genetic Basis of Pigmentation Using Autosomal and Uniparental Markers. PLoS Genet 10(7): e1004488. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004488.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. The Arawak Languaje of Guiana. Page 181. Cambridge University Press. cambridge.org.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. La langue arawak de Guyane, Présentation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français-arawak. Page 123. IRD Éditions. Marseille. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr.

- Pet, Willem J. A. 2011. A Grammar Sketch and Lexicon of Arawak (Lokono Dian). Page SIL e-Books.

- Moravian Brothers. 1882. Arawakisch-Deutches Wörterbuch, Abschrift eines im Besitze der Herrnhuter Bruder-Unität bei Zittau sich befindlichen-Manuscriptes. Grammaires et Vocabulaires Roucouyene, Arrouague, Piapoco et D’autre Langues de la Région des Guyanes, par MM. J. Crevaux, P. Sagot, L. Adam. Page 134. Paris, Maisonneuve et Cie, Libraries-Editeurs. http://books.google.com.

- Bernal Valdés, Sergio. 2013. La conquista lingüística aruaca de Cuba [The Arawakan Linguistic Conquest of Cuba]. In Revista de la Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba, José Martí. Year 104 No.1. Page 166.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1970. Para la historia de las voces “conuco” y “guajiro”[For the History of the Voices “Conuco” and “Guajiro”]. In Boletín de la Real Academia Española. L, Notebook CXC, May-August.

- Goeje, C. H. de. cit. Pages 193, 196.

- Goeje, C. H. de. cit. Pages 197-198.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. cit. Pages 34-35.

- Colón, Hernándo. 1892. Historia del Almirante Don Cristobal Colón. [History of Admiral Christopher Columbus] First Volume. In Colección de libros raros o curiosos que tratan de América. Fifth Issue. Page 280. http://books.google.com.

- Real Academia de Historia. 1885. Testimonio remitido por los oidores de Santo Domingo que fueron a la isla Fernandina del 13 de marzo de 1522, de la declaración tomada á Vasco Porcallo de Figueroa, sobre las alteraciones en la villa de Sancti-Spíritus [Testimony Sent by the Judges of Santo Domingo who Went to Fernandina Island on March 13, 1522, of the Statement Taken from Vasco Porcallo de Figueroa About the Alterations in the Village of Sancti Spíritus]. Colección de Documentos Inéditos Relativos al Descubrimiento, Conquista y Organización de las Antiguas Posesiones Españolas de Ultramar. Tomo 1, Isla de Cuba. Madrid. Project Gutenberg Ebook.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1989. Mitología y artes prehispánicas en las Antillas [Mythology and pre-Hispanic arts in the Antilles]. Page 60. Editorial Siglo Veintiuno.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. cit. Pages 45-46.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. cit. Page 30.

- Pané, fray Ramón. Op. cit. Page 50.

- Researchers Racso Fernández Ortega and Juan Cuza Huart, in their article, Opiyelguobirán y Maquetaurie Guayaba. Nueva propuesta de interpretación [Opiyelguobirán and Maquetaurie Guayaba. New Interpretation Proposal], published in Cuba ArqueológicaYear III, núm. 22010, make a proposal of etymology, where they consider that the suffix –el is a form of the particle yel –ii–el–, indicator or executor of the action related to the verb “cry”, however, for the reasons given in this article, we differ from their proposal.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1909. Apologética historia de las Indias [Apologetic History of the Indies]. In Serrano y Sanz. Historiadores de Indias. Volume I. Page 518. Madrid. http://www.archive.org.

- Moreira de Lima, Lilián J. 2018. Vida cotidiana y organización social de las comunidades aborígenes de Cuba [Daily Life and Social Organization of the Aboriginal Communities of Cuba]. In Cuba: arqueología y legado histórico. Page 62. Ediciones Polymita. City of Guatemala.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1956. Historia de las Indias [History of the Indies]. III. Page 90. Biblioteca Ayacucho, Caracas.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. Relación del primer viaje de Cristobal Colón para el descubrimiento de las Indias [Account of the First Voyage of Christopher Columbus]. Pages 24-25. In Relaciones y cartas de Cristobal Colón. 1892. Madrid.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1909. Apologética historia de las Indias [Apologetic History of the Indies]. In Serrano y Sanz. Historiadores de Indias. Volume I. Page 86. Madrid.

- Martí, José. 1991. Antonio Bahciller y Morales. In Obras completas. Volume 5. Page 150. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. La Habana.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1909. Volume I. Op. cit. Page 537.

- Engels, Federico. 2006. El origen de la familia, la propiedad privada y el estado [The origin of the familily, private property and the state]. Page 105. Collection Clasicos del marxismo. Foundation Federico Engels. Madrid.

- Fernández Ortega, Racso y Cuza Huart, Juan. 2010. Op. cit.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1989. Op. cit. Page 64.

- Oliver, Jose R. 1988. El centro ceremonial de Caguana, Puerto Rico. Simbolismo iconográfico, cosmovisión y poderio caciquil taíno de Boriquen [The Ceremonial Center of Caguana, Puerto Rico. Symbolism, Cosmovision and Taino Cacique Power of Boriquen]. Page 138. British Archaeological Raports. International series. Archaeopress, Oxford.

- Oliver, Jose R. 2009. Caciques and Cemí idols: the web spun by Taino rulers between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Página 87. The University of Alabama Press.

- Fundación Cultural Educativa Inc. –Instituto de Cultura Puertoriqueña. 2011. 5to Centenario (1511-2011) de la rebelión taína [Fifth Centenary (1511-2011) of the Taino Rebelion].

- Martyr D’Anghera, Peter. 1912. The Eight Decades of the Orbe Novo. First Decade, Book IX. Volume One. Page 175. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. New York and London. The Knickerbocker Press.

- Levi-Strauss, Claude. 2000. Mitológicas IV. El hombre desnudo [Mythologiques IV. The Naked Man]. Page 577. Siglo Veintiuno editores. México D.F.