The aboriginal contribution to the expressions of popular religiosity in Cuba is the least visible among the legacy of the three main roots of Cuban identity (Spanish, African and aboriginal); nevertheless, it exists and is expressed through mostly syncretic manifestations: the symbol and legend of the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, patron saint of Cuba1; the cordon spiritism2; the use of maracas and tobacco in Afro-Cuban religious rites; the myths, such as the Güije or Jigüe, the Cagüeiro and the Mother of Waters3.

The aboriginal gods or cemís did not survive the tsunami of repression, discrimination and oblivion generated by the Spanish conquest. Of them, possibly Atabey, also known as Atabeira, the ancestral mother, is the one who has left the most visible mark on Cuban culture; firstly because she is associated, together with the Christian Mary and the Yoruba Ochún, with the emergence of the legend and symbol of the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre; but also because her name and her myth have a special attraction, not fully defined in nature, but certainly related to the intuition, more than the awareness, of the legacy of our indigenous roots: one out of every three Cubans comes from an aboriginal ancestral mother, as confirmed by science4. This perhaps explains the motivation behind the naming of a Havana neighborhood, a hotel and a restaurant, among other places, after her, and even the composition of an electroacoustic musical work inspired by her5.

But, who is really this goddess? What do we know about her? The most reliable information comes from Friar Ramón Pané, a Catalan religious of the order of the Hieronymites, commissioned by Christopher Columbus to “learn and know about the beliefs and idolatries of the Indians”, who learned some of their language and lived among them for several years, during which he wrote “An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians”, the only direct source on the religion of the Arawak aborigines of the Antilles, whose original was not preserved and has reached the present through translations and summaries. In it the friar points out:

Each one, in worshipping the idols they have at home, called by them cemís, observes a particular mode and superstition. They believe that he is in heaven and is immortal, and that no one can see him, and that he has a mother, but no beginning, and they call him Yúcahu Bagua Maórocoti, and his mother they call Atabey, Yermao, Guacar, Apito and Zuimaco, which are five names6.

From this excerpt we can draw the following conclusions:

a) Atabey is the primordial among the aboriginal cemís, the oldest one, a quality associated with the status and forms of treatment within the culture of the Arawak peoples, as we will see later on.

b) She is also the first mother, which points to her relationship with fecundity, fertility and childbirth. The fact that she is the progenitor of Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti, the cemí responsible for the fertility of crops, suggests that she is the opposite complement of the latter, the female fertile principle7.

Other evidence from archaeology and the chronicles of the Indies also seem to confirm these attributes of the goddess:

Small clay idols representing pregnant women, attributed to Atabey, have been found in the eastern region of Cuba. According to Guarch and Querejeta, they were kept in the bohíos or caneyes (circular wood and thatch huts) and were used to facilitate women’s childbirth8. This coincides with an observation of Christopher Columbus, collected by his son Ferdinand in the Admiral’s biography:

Most of the caciques have three stones, to which they and their people have great devotion. The first, they say, is good for the cereals and vegetables they have sown; the second, for women to give birth without pain, and the third for water and sun when they are needed9.

Friar Ramón Pané also mentions the cemís that facilitate women’s childbirth:

The stone cemís are of various shapes. There are some that (…) are the best for giving birth to pregnant women10.

Based on the etymology of the names of Atabeira, carried out by Daniel G. Brinton and José Juan Arrom, it has been proposed that she must also have been related to the waters, the moon, the tides and menstruation11. However, the etymological analysis of the names of the goddess carried out by these scholars is partial and inconclusive, which shows the need for a new revision of the subject in the light of the advances in the study of the Arawak languages. This is precisely the purpose of the present work.

Daniel G. Brinton was an American archaeologist, ethnologist and linguist of the 19th century. In 1871 he published an extensive article entitled The Arawak language of Guiana and its linguistic and ethnological relations, which demonstrated for the first time the relationship between the Lokono of the Guianas and the languages spoken by the aborigines of the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. His proposed etymology of the name Atabeira belongs to this article.

The merit of Brinton’s work, a classic of comparative linguistics of the Americas, is indisputable. However, his proposals for etymology are not always correct. This was the opinion of C. H. de Goeje, a renowned Dutch researcher, who, with the endorsement of more than three decades of study of the Arawak languages, pointed out: “Brinton succeeded in establishing affinities between Taino and the Arawak of Guyana, but his etymologies are often erroneous” (Brinton a réussi à constater des affinités entre le Taino et l’Arawak de la Guyane, mais ses étymologies sont souvent erron)12.

For his analysis of the name Atabeira, Brinton relies on a passage from the mythology of the Guianas, collected during the first half of the 19th century by the English missionary W. H. Brett, which deals with Orehu, The Mother of Waters, a feminine deity that the American ethnologist compares to the Island Arawak goddess. Below we reproduce the above-mentioned passage and the proposed etymology that appear in Brinton’s article:

Let us place side by side with these ancient myths the national legend of the Arawacks. They tell of a supreme spiritual being Yauwahu or Yauhahu. Pain and sickness are the invisible shafts he shoots at men, yauhahu simaira, the arrows of Yauhahu, and he it is whom the priests invoke in their incantations. Once upon a time, men lived without any means to propitiate this unseen divinity; they knew not how to ward off his anger or conciliate him. At that time the Arawacks did not live in Guiana, but in an island to the north. One day a man named Arawanili walked by the waters grieving over the ignorance and suffering of his nation. Suddenly the spirit of the waters, the woman Orehu, rose from the waves and addressed him. She taught him the mysteries of semeci, the sorcery which pleases and controls Yauhahu, and presented him with the maraka, the holy calabash containing white pebbles which they rattle during their exorcisms, and the sound of which summons the beings of the unseen world. Arawanili faithfully instructed his people in all that Orehu had said, and thus rescued them from their wretchedness. When after a life of wisdom and good deeds the hour of his departure came, he “did not die, but went up.”

[…]

The proper names which occur in these myths, date back to the earliest existence of the Arawacks as an independent tribe, and are not readily analyzed by the language as it now exists. The Haitian Yocauna seems indeed identical with the modern Yauhahu. Atabes or Atabéira is probably from itabo, lake, lagoon, and era, water, (the latter only in composition, as hurruru, mountain, era, water, mountain-water, a spring, a source), and in some of her actions corresponds with Orehu13.

In the reproduced fragment it can be seen that Brinton identifies Yauhahu with the Island Arawak cemí Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti (he names it Yocauna following the way Peter Martyr D’Anghera recorded it), but in the mythology of the Arawaks of the Guianas, Yauhahu is a generic term for forest spirits or weed spirits that harm or make people sick, and his name is used in translations of the bible to name the devil and impure spirits, as summarized from several sources by C. H. de Goeje, who also points out that the name means “he who wanders through space”14, all of which is radically different from what we know about Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti, a main deity of Island Arawak mythology who lives in the sky and is a fruitful cemí that promotes fertility and fecundity15.

Brinton also identifies in Atabeira some of the functions of Orehu, which leads him to suppose that the former, like the latter, is an aquatic being and to base his proposed etymology on this hypothesis. However, the aquatic nature of Orehu does not coincide with what is known about Atabeira nor with the Antillean iconography associated with this goddess.

In Cuba, the myth of the Mother of Waters was studied by Samuel Feijóo, an outstanding writer and researcher of peasant folklore, who in his work, Cuban Mythology, published in 1980, includes it, due to its values and extension, within the major Cuban mythology. This author points out the Amerindian origin of the myth and refers that:

In Cuba, in general terms, the Mother of Waters is neither a mermaid nor a goddess, nor is she an attractive and terrible spirit of the waters. In Cuba the Mother of waters is, we repeat, an enormous non-poisonous boa, aggressive or not, malignant or not, whistling, and relatively well-wisher because she keeps the waters flowing wherever she inhabits them16.

In certain versions of the Amazonian myth, Orehu is also a serpent, as can be seen in the aforementioned work by Feijóo17 and in that of C. H. de Goeje, The Arawak Language of Guiana18.

As for Brinton’s etymology proposal itself, we find that era does not mean ‘water’ in Lokono (Arawak language of the Guianas), but ‘juice’19 and the word for ‘water’ in that same language is: oni-abu, oini, wuni-abu20. The expression hurruru-era does not literally mean ‘water-from-the-mountain’, but ‘juice from the mountain’ or ‘juice from the earth’ and seems to be an expression with a figurative sense to refer to the ‘spring’ or ‘fountain’. As we have pointed out in other works, both the Lokono and the Island Arawak make frequent use of the figurative sense with even poetic constructions on certain occasions21.

On the other hand, the phonetic similarity of itabo with Atabey is partial and no other reason can be found to link the two words. The bias in the analysis originates in its forced link with the aforementioned hypothesis about the aquatic nature of Atabeira.

Finally, the expression ‘juice of the lake’ or ‘juice of the lagoon’, which would result from Brinton’s etymology, does not seem to make sense or correspond to the name Atabeira.

The eminent Cuban pedagogue and researcher José Juan Arrom, published in 1975 his important work, Mythology and Pre-Hispanic Arts of the Antilles, about which the Puerto Rican archaeologist José R. Oliver points out:

It is one of the first investigations on Taino religion that tries to reconcile ethnohistoric, linguistic and archaeological documentation (…). He [Arrom] was the first to establish -in a convincing way- a correspondence of the 12 Cemí characters with specific archaeological objects coming from the Greater Antilles”22.

In that work, Arrom, after examining Brinton’s etymology, makes the following proposal:

In fact, itabo is a term still used in the Antilles with the meaning of “puddle or deposit of fresh, clean water …with springs flowing from the bottom”. And in the etymology proposed by Brinton the important thing would be to emphasize the presence of clear water flowing from the bottom. But the root that enters in the composition of Attabeira could also have been atté, attette, registered in several Arawak vocabularies as a vocative of ‘mother’. According to these vocabularies, it is a term used by children to call their mother and also by adults to address an old woman. Atté is equivalent to ‘Mom’, ‘Mommy’ and also as a sign of respect, to ‘Mother’, ‘Lady’. And this root, modified by the linked suffix mentioned by Brinton, would give us ‘Mother of the Waters’, that is to say, the same name of the mythical figure that appears in the other Amerindian theogonies23.

In our opinion, this variant of etymology is correct in what differentiates it from Brinton, but errs in what it shares with him: indeed, the word atté or attete, ‘mother’, corresponds to the most important attribute of Atabeira and phonetically it seems to fit within the structure of the name. Regarding the rest of the proposal, we have already explained the elements for which we consider it wrong.

Arrom also analyzes a second name for the goddess, guacar, and states the following:

Guacar seems to be composed of two semantemes. Wa is the pronominal prefix that in Arawak languages means ‘our’. And kar may have been an apocopated form of katti ~ kairi ‘moon, month’, a term composed in turn by ka ‘force’ and iri ‘tide, menstruation’. Had that term corresponded to the forms just mentioned, Atabey, Attabeira ‘the Mother of the Waters’ could also have been a divinity related to the moon, tides and menstruation.

These analyses are, of course, hypothetical in nature. But it is very significant that they all converge towards the same central idea of a female deity related to motherhood24.

It seems to be a tendency in different proposals of etymology of Island Arawak words to automatically assign the meaning ‘we’ to the morpheme gua (wa) without considering other possibilities. In reality, ‘we’ is only one sense or acceptation of one of the various meanings that this morpheme has in both Island Arawak and Lokono25. It is true that the sense ‘we’ is frequently used, but there are numerous examples where this is not the case, a subject to which we will devote a future paper. In the present case, the morpheme gua (wa) in the structure of the word guacar also has a meaning different from ‘we’, which we will examine later in our proposed etymology.

As for Atabeira’s possible relationship with the moon, the latter is a male character in the mythology of the Arawaks, which makes such a link unlikely. Arrom himself includes in his 1975 work a legend according to which the moon impregnated a young girl whom she visited incognito at night. The girl’s mother smeared the lover’s face with soot and that is why the moon has spots26. These elements indicate that the supposed meaning of ‘our moon’ corresponding to the proposed etymology is improbable.

The realization of a proposal for an etymology of Atabeira’s names faces several difficulties. As we noted above, Pané’s original, written between 1495 and 1498, was not preserved and his work has come down to the present through translations and abridgements: Peter Martyr D’Anghera made a Latin compendium in a letter addressed to Cardinal Ludovico de Aragón, published in 1504; Bartolomé de Las Casas made an extract that he included in his Apologetic History of the Indies; Ferdinand Columbus, the Admiral’s son, included it in its entirety in his father’s biography, written in Spanish, but he died in 1539 and left it unpublished; an Italian translation of it was made by Alfonso de Ulloa in 1571. The manuscript of Ferdinand Columbus was also lost, so that only the versions of Ulloa, D’Anghera and Las Casas are known today27.

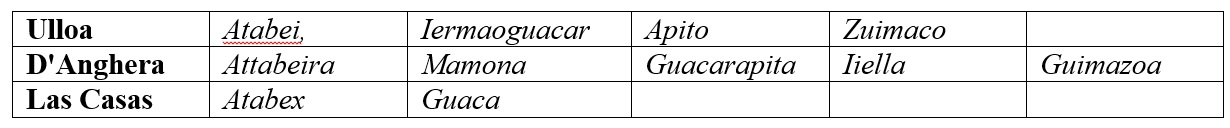

The forms in which the names of Atabeira were recorded in these versions (Table 1) and the differences between them, were commented by Arrom as follows: “The evident corruption of the texts, with variants that sometimes it is almost impossible to relate to each other, makes the task of attempting the linguistic analysis of these names difficult and risky”28.

Table 1

The names of Atabeira according to Alfonso de Ulloa, Peter Martyr D’Anghera and Bartolomé de Las Casas29.

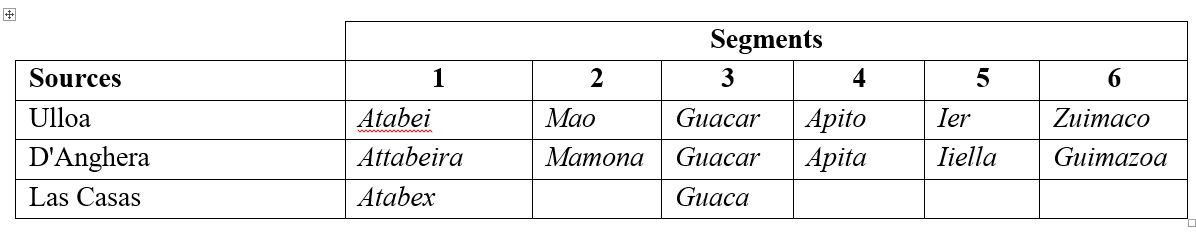

However, within these variants it can be seen that D’Anghera’s is the most complete and within it are included all the segments present in the other two (Table 2). D’Anghera was a scientist of his time and cannot be accused of inventing or imagining non-existent content in the text. Moreover, he was the first of the three to have access to the manuscript that must have been in the best state of preservation at the time.

Table 2

Segments of Atabeira names ordered according to the D’Anghera’s variant.

On the basis of these considerations, we selected the D’Anghera’s variant as the main one for the linguistic analysis, although we also used the Ulloa’s variant in the identification of the Island Arawak words and their cognates from the lokono.

The first word is Attabeira. We agree with Arrom that the morpheme atta corresponds to the Lokono vocative Atte or Attete, ‘mother’, a main characteristic that identifies the goddess, which explains why this characteristic is the first one mentioned.

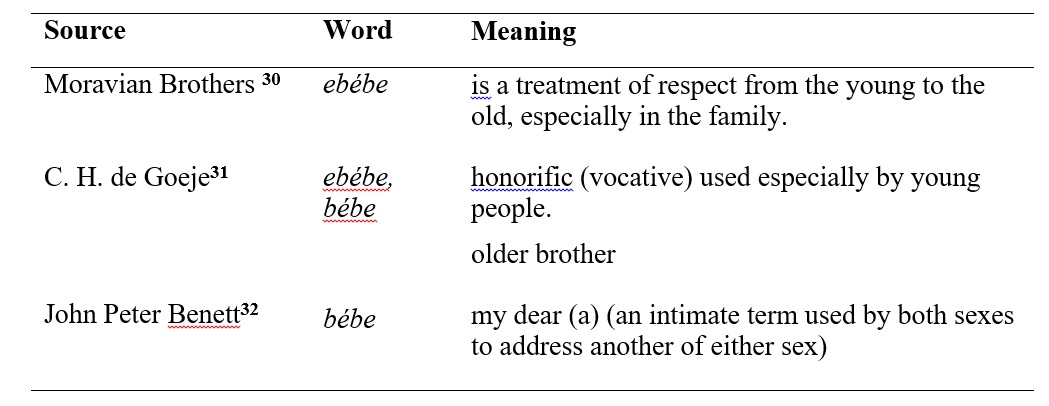

As Arrom points out, Attete is also used as a sign of respect to address older women, which coincides with another main characteristic of Atabeira: its quality as a primordial spirit. The Arawaks addressed their elders with a special respect and another frequently used vocative is the word bébe or ebébe. Their meanings in Lokono are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Lokono meanings of bébe and ebébe.

The Arawaks were so rigorous in their respectful treatment of elders that even among the cattle they identified the eldest animal and called it ebebe, and noted with great precision whether people were older or younger, even for a week or a day, a custom reported by the Moravian Brothers missionary Christlieb Quandt, who observed it in Suriname during the XVIII century33.

If they were so in their general dealings, what is to be expected in relation to the primordial goddess? Of course the honorific vocative ebébe must be, in some form, part of her name.

In a previous work, we analyzed how ebébe or bébe is found in the structure of the toponym Guanahatabibes, the ethnic denomination guanahatabey and the anthroponym Guanahatabenequena.34

The suffix -ey is a form related to that of the Lokono oyo, iyu, ‘mother’ (in this case it is not a vocative).35 Ancient Arawak society was subdivided into matrilineal families and clans, where “a child is considered to belong to its mother’s clan, and a man who marries becomes a subject of his father-in-law”.36 In this sense, -ey means ‘of the family’, ‘of the lineage’, ‘of the class’, ‘of the tribe’.

Consequently, bébe, ‘elder’ + -ey, ‘of the lineage’ = bey, ‘of the lineage of the elders’, ‘ancestral’, where the reduction of one syllable (be) occurs in the new word. Compare with the Lokono word hebeyo, ‘ancestor’37, which is composed of the morphemes hebe, ‘old’38 (applied to living beings) + -yo, ‘mother’. Ebebe and hebe are two words of closely related etymology.

In this way we arrive at the meaning of Atabey, ‘ancestral mother’.

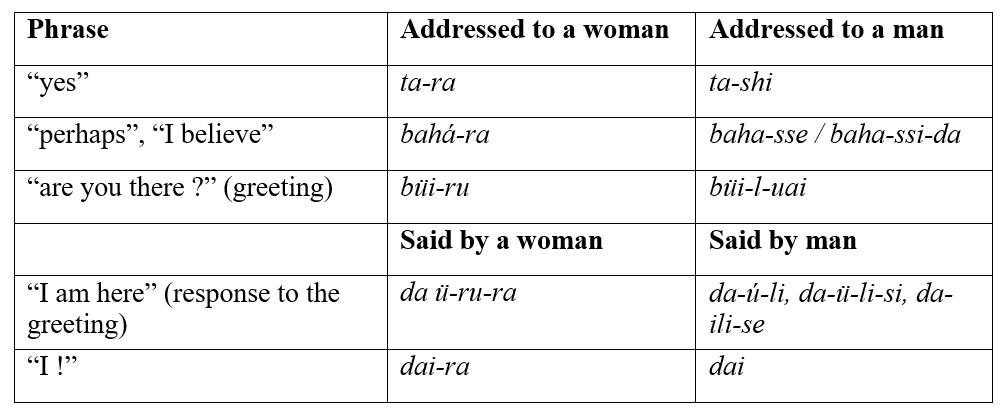

As for –ra, in this case it is a feminine emphatic particle, which is used in Lokono by women or to address them. In Table 4 we present some examples collected by C. H. de Goeje.

Table 4

Examples of use in Lokono of the feminine emphatic particle -ra39

The presence of this particle in the structure of Atabeira’s name reveals that we are addressing the goddess.

To conclude the linguistic analysis of the word Atabeira, a clarification is necessary. As Oliver points out, “in many South American myths women are frequently represented as creatures with fish, amphibian, or reptilian qualities, animals directly associated with the aquatic and humid environment “40. This is also expressed in the language: C. H. de Goeje refers that the phoneme /t/ is used in Lokono words that indicate the feminine gender, but also describes the action of “flowing” (ite, ‘blood’, a-ti, ‘drinking’, etc), and the suffix -ra, which is used in phrases addressed to or pronounced by women, also appears in connection with flowing41.

The phoneme /t/ and the suffix -ra are found in the name Atabeira, which in a certain way motivated Brinton’s proposal; however, the analysis reveals that its presence is due to the fact that we are naming a woman and not to the supposed aquatic attributes of the goddess.

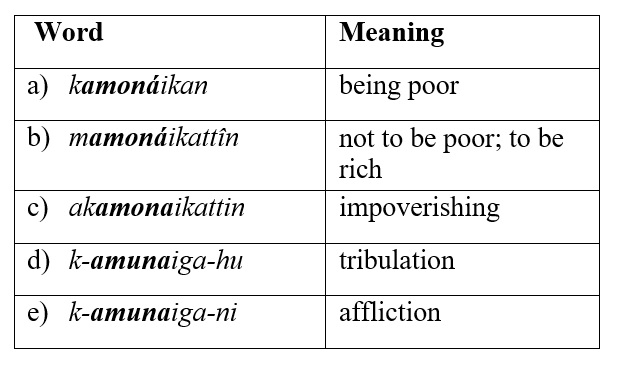

The next word in the D’Anghera’s variant is Mamona. In Lokono there is the root amona or amuna from which several words are created and which are presented in Table 5. Let us pay attention to two of them: kamonáikan, ‘to be poor’ and mamonáikattîn, ‘not to be poor’, ‘to be rich’. In the first one, the attributive prefix ka is present and in the second one, the privative prefix ma. In both cases a phoneme /a/ is eliminated by elision when the word is formed. These prefixes are distinctive of the Arawak languages. The first indicates the presence of something and the second indicates the absence of something.

Now we can conclude that the root amona / amuna means ‘poverty’ and possibly also ‘sadness’, two concepts undoubtedly related to each other in the ancient Arawak culture. Thus, mamona means ‘plenty’ and is possibly also related to the concept of ‘happiness’. Poverty, in a society where money did not exist and goods were distributed equally, was mainly due to contingencies such as bad harvests and natural disasters.

Table 5

Lokonos words with the root amuna / amona42, 43.

The third word in the D’Anghera’s variant is Guacarapita. We are going to divide it for its analysis in two segments: guacar and apito. As can be seen, the second appears in the form recorded by Ulloa’s variant.

The segment guacar does not seem to correspond to Island Arawak, where the words, as Cuban linguist and researcher Sergio Valdés Bernal points out, “are formed by open syllables, that is, ending in vowels”. As a possible Lokono cognate we find the word registered by C. H. de Goeje as wakarra, wakorra, ‘to be skinny’, ‘to languish’44 and by the Moravian Brothers as wákarran ‘to be skinny’45. C. H. de Goeje notes that the morpheme wa in this word means ‘contracted’46, one of the numerous cases in which it has a meaning other than ‘we’.

Regarding apito, we will consider that its structure is composed of the root api and the suffix -to. An exception occurs here where Island Arawak differs from Lokono. In the proto-Arawak that originated the Arawak language family, apɨ means ‘bone’, as recorded by various authors, including David L. Payne47. Many languages of the family retained forms of the word very similar to Proto-Arawak, including Island Arawak, but in Lokono this word took the form of abona48.

With respect to the suffix -to / -tu, as we explained in a previous work49 , it is a form of the word oto (also utu, otu, uttu), which means ‘daughter’50. It has, among its functions, to form nouns that act like adjectives and attributive adjectives. Let us see some examples in lokono51, 52.

- ipirun, ‘to be big’; ipirutu, ‘something big’.

- wádin, ‘to be long’; wáditu, ‘something long’.

- ikihi, ‘fire’; ikihi-tu kaspara, ‘flaming sword’.

- sa, ‘good’, ‘holy’; sa-tu ajia-hu, ‘holy word’, ‘the gospel’.

Thus, api, ‘bone’ + -to, (suffix forming nouns that act like adjectives) = apito, ‘bony’.

By integrating the meanings found in the compound word, we obtain: guacara, ‘skinny’ + apito, ‘bony’ = guacarapito, ‘skinny to the bone’.

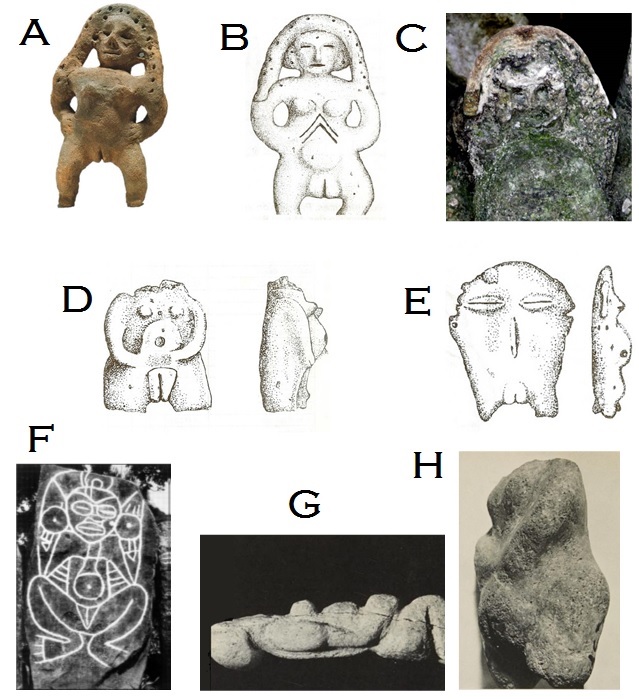

Bones in the Island Arawak agro-pottery culture were a symbol of death and the spirits of the ancestors, and were sometimes used to invoke the forces of the spirits as part of the idols53. The religious art they developed is full of skeletonized images, among them some idols attributed to Atabeira (Figure 1), which exhibit bones in the thorax symbolizing her antiquity and her condition of primordial or ancestral mother, the first ancestor of all spirits. These elements of judgment allow us to understand the reasons for calling the goddess “skinny to the bone”.

The next word is Iiella. Its cognate in Lokono is üya, also huia, ia, ueja úeja, úejahu, recorded by the Moravian brothers54 and C. H. de Goeje55 with several meanings, among them, ‘spirit’.

As the last word of the name variants, we will select the form recorded by Ulloa, Zuimaco. We appreciate that it is related to the Lokono cognate simaki, simaka, ‘to call’, ‘to yell or cry out’. Willem J. A. Pet, a researcher who studied the grammar and lexicon of Lokono in Suriname, collects in his work, A Grammar Sketch and Lexicon of Arawak (Lokono Dian), examples that illustrate the various forms of personal pronouns in sentences with the use of this word56. Some of them are presented below:

- by-symaka-i; you-call-him;‘you called him’.

- li simaka-o; he call-us; ‘he called us’.

- ly-simaka bo; he-call you; ‘he called you’.

- tho simaka-i; she call-him; ‘she called him’.

- thy-simaka je; she-call-them; ‘she called them’.

- we simaka no; we call her; ‘we called her’.

- wa-simaka dei; we-call him; ‘we called him’.

Of these examples, it is the form simaka-o that we consider to correspond to zuimaco. Thus, simaka-o in the context of the analyzed words means ‘you called us’.

Having completed the analysis by individual words, we can now reconstruct the names of Atabeira with their meanings: ‘‘Ancestral Mother, Spirit of Plenty Skinny to the Bone, you called us’‘.

This form corresponds to three names: “Ancestral Mother”, “Spirit of Plenty” and “Skinny to the Bone Spirit”. The opinion has been expressed that because Atabeira had five names, his rank was even higher than that of Yucahu Bagua Maórocoti. Now we see that there were also three. Each name corresponds to an attribute. In the case of Atabeira, those of ancestral mother, promoter of fertility and primordial spirit. In the case of Yucahu, according to Arrom’s etymology, those of promoter of fertility (Yucahu, ‘Spirit of the Yucca’), Spirit of the Sea (bagua, ‘sea’) and first among the male spirits (Maórocoti, ‘Being without Male Ancestor’) 57.

The fact that Atabeira and Yucahu have the same number of names is consistent with the symmetry in the worldview of the Island Arawak agro-pottery culture that considered both cemís as a duality.

It is noteworthy that the last word is not a name. Evidently the complete expression, including the names, is a ritual phrase that was very probably pronounced during the celebration of the religious rites (cohoba ceremony) to this goddess. It also stands out that it is she who calls instead of being invoked, which could be related to the fact that during the cohoba ceremony the cemís spoke through the cacique in trance under the effect of the hallucinogenic substances (see entry Yao, space of the spirit).

Let us now explore the link between Atabeira’s names and his iconography. In a generalization of the image of the idols attributed to her, Cuban researchers José M. Guarch and Alejandro Querejeta make the following description:

The image that the Arawaks bequeathed us is that of a naked woman, often pregnant. The ceramic figures show her with her arms in jars, her hands on her hips and adorned with large headdresses. Other times no arms are visible and they are very schematic and symbolic. In general, all of them have a small size58.

Figure 1 shows eight images of idols attributed to Atabeira. Five of them (A, B, D, E and F) show their sex explicitly, a circumstance that, according to Oliver, allows them to be associated with the metaphorical chains of female fertility and procreation59. All the images represent pregnant women (D, E and H), in labor position (G) or with bulging abdomens (A, B, C and F), features that are associated with the same attributes and are expressed in the names of “Ancestral Mother” and “Spirit of Plenty”.

Three of the images symbolically show their ancestral origin, antiquity and rank, through the representation of the ribs (B, C and F). Four also manifest their rank through the headdresses and ornaments60 (A, B, C and F). These attributes are expressed in the names “Ancestral mother” and “Skinny to the Bone Spirit”.

The image of the petroglyph from the Caguana Ceremonial Center exhibits frog legs. The frog is a symbol of fecundity and fertility in the Arawak agro-pottery culture (see entry Yao, space of the spirit), which confirms that these attributes were assigned to Atabeira.

Oliver also associates the frog limbs “with the aquatic and humid environment “61, a link that indeed exists, but is indirect in the case of Atabeira, whose names do not refer to any aquatic attribute. As this author points out, other male cemís from the Caguana petroglyphs also present this type of limbs.

Figure 1

Some idols attributed to Atabeira

As final ideas of this work, we emphasize that we were able to clarify aspects of the cult of Atabeira, confirming in some cases and refuting in others the attributes that were assigned to her. Now we have a more accurate representation of how our Aborigines conceived her and we can use this knowledge in the study of the aboriginal culture and its legacy.

The potential of linguistic analysis to clarify aspects of Island Arawak culture is evident.

Notes

- Portuondo Zúñiga, Olga. 2002. La Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre: Símbolo de cubanía. Agualarga Editores. Madrid.

- García Molina, José Antonio et. al. 2007. Huellas vivas del indocubano. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. La Habana.

- Feijóo, Samuel. 1986. Mitología cubana. Editorial Letras Cubanas. La Habana.

- Marcheco-Teruel B, Parra EJ, Fuentes-Smith E, Salas A, Buttenschøn HN, et al. 2014. Cuba: Exploring the History of Admixture and the Genetic Basis of Pigmentation Using Autosomal and Uniparental Markers. PLoS Genet 10(7): e1004488. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004488.

- Iha Rodríguez, Javier. 2021. El mito de Atabey: el folklor imaginario y evocación sonora. https://universoculturalcubano.wordpress.com/2021/09/08/el-mito-de-atabey-folklor-imaginario-y-evocación-sonora/.

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Relación acerca de las antiguedades de los indios (nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices de José Juan Arrom). Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. La Habana.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. El centro ceremonial de Caguana, Puerto Rico. Simbolismo iconografico, cosmovisi6n y el poderio caciquil Taino de Boriquen. BAR Publishing, Oxford. Página 113.

- Guarch Delmonte, José M. y Querejeta Barceló, Alejandro. 1992. Mitología aborigen de Cuba. Deidades y personajes. Publicigraf. La Habana. Página 28.

- Colón, Fernando. 1892. “Historia del Almirante Don Cristobal Colón”. Primer Volumen. Páginas 277-280. En Colección de libros raros y curiosos que tratan de América. Tomo quinto. https://books.google.com.

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Op. cit. Páginas 42-43.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Mitología y artes prehispánicas de las Antillas. Editorial Siglo XXI. México. Páginas 45-54.

- De Goeje, C. H. 1939. “Nouvel examen des langues des Antilles: avec notes sur les langues Arawak-Maipure et Caribes et vocabulaires Shebayo et Guayana (Guyane)”. En Journal de la Société des américanistes, NOUVELLE SÉRIE. Vol. 31. No. 1 (1939). Página 1. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24601998.

- Traducción en: Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Op. cit. Páginas 44-45. Original en inglés en: Brinton, D. G. 1871. The Arawak Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological Relations. McCalla & Stavely, Printers, Philadelphia. Página 18.

- De Goeje, C. H. 1928. The Arawak Language of Guiana. Cambridge University Press. New York. Página 200. Descargado de www.cambridge.org.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Op. cit. Páginas 19-39.

- Feijóo, Samuel. 1986. Mitología cubana. Editorial Letras Cubanas. La Habana. Página 188.

- Feijóo, Samuel. 1986. Op. cit. Páginas 179-184.

- De Goeje, C. H. 1928. Op. cit. Página 198.

- De Goeje, C. H. 1928. Op. cit. Páginas 167, 215.

- De Goeje, C. H. 1928. Op. cit. Página 35.

- Ver entrada Guanajay, tierra alta, en laotraraiz.cu.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. Op. cit. Páginas iv, 109.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Op. cit. Páginas 45-47.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Op. cit. Página 47.

- De Goeje, C. H. 1928. á. Páginas 158-166.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Op. cit. Páginas 155-156.

- Arrom, José Juan en Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Relación acerca de las antiguedades de los indios (nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices de José Juan Arrom). Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. La Habana. Páginas 3-21.

- Arrom, José Juan. 2011. “La virgen del Cobre: historia, leyenda y símbolo sincrético”. En José Juan Arrom y la búsqueda de nuestras raíces. Editorial Oriente y Fundación García Arévalo. Page 149.

- Pané, fray Ramón. 1990. Relación acerca de las antiguedades de los indios (nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices de José Juan Arrom). Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. La Habana. Page 59.

- Hermanos Moravos. 1882. “Arawakisch-Deutches Wörterbuch, Abschrift eines im Besitze der Herrnhuter Bruder-Unität bei Zittau sich befindlichen-Manuscriptes”. En Grammaires et Vocabulaires Roucouyene, Arrouague, Piapoco et D’autre Langues de la Région des Guyanes, par MM. J. Crevaux, P. Sagot, L. Adam. Paris, Maisonneuve et Cie, Libraries-Editeurs. Page 110. http://books.google.com.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Pages 196, 238.

- Bennett, John Peter. 1995. Twenty-Eigth Lessons in Loko (Arawak). A teaching guide, Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology, Georgetown, Guyana. Page 26.

- Quandt C. 1807. Nachricht von Suriname und seinen Einwohnern sonderlich den Arawacken, Warauen Und Karaiben. Leipzig. Page 268. http://books.google.com.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2024. El lugar, la gente y la esposa: la clave común de tres nombres aruacos. https://www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. La langue arawak de Guyane, Présentation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français-arawak. IRD Éditions. Marseille. Page 181. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 197.

- Bennett, John Peter en Patte, Marie France. 2011. Op. cit. Page 92.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Pages 148, 198.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 209.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. Op. cit. Page 152.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 245.

- Hermanos Moravos. 1882. Op. cit. Pages 131, 143, 82 (incisos a,b y c).

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 82 (incisos d y e).

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 44.

- Hermanos Moravos. 1882. Op. cit. Page 163.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 161.

- Payne, David L. 1991. “A classification of Maipuran (Arawakan) languages based on shared lexical retentions”. En Derbyshire, D.C.; Pullum, G. K. (editores). Handbook of Amazonian Languages. Vol. 3. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Page 396.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 216.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2024. Cauto: el río y el nombre. https://www.laotraraiz.cu.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Pages 43, 193.

- Hermanos Moravos. 1882. Op. cit. Pages 175 y 177 (incisos a y b)

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Page 70 (incisos c y d).

- García Arévalo, Manuel. 2019. Taínos, arte y sociedad. Banco Popular Dominicano. Santo Domingo. Pages 171,182. https://issuu.com.

- Hermanos Moravos. 1882. Op. cit. Page 157.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op. cit. Pages 203-204.

- Pet, Willem J. A. 2011. A Grammar Sketch and Lexicon of Arawak (Lokono Dian). SIL e-Books. Page 13. https://sil.org.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Op. cit. Pages 20-22.

- Guarch Delmonte, José M. y Querejeta Barceló, Alejandro. 1992. Mitología aborigen de Cuba. Deidades y personajes. Publicigraf. La Habana. Pages 27-28.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. Op. cit. Page 152.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. Op. cit. Pages 152-153.

- Oliver, José R. 2016. Op. cit. Page 152.