The locality of Guanajay in the current province of Artemisa, west of Havana, was a well-known place since the early colonial times in Cuba. In the Chapter Acts of the City Council of Havana, in the town council meeting of 31 December 1557, it is recorded:

It was agreed by the said Lords that after the storm and hurricane passed the roads from which this village draws its supplies, which are the Matanzas road, the Matabanó road and the Guanajay road, they are closed and blocked because of the said storm and hurricane, and it is in the service of God and His Majesty and the good and prosperity of this town that they be opened so that they can be walked: therefore, they decided what each one has to contribute to the repair of the said roads between the Lords Antonio de la Torre, Diego de Soto and Diego Lopez Duran, so that after the day of the Three Wise Men it will be opened, which they signed1. (Emphasis added).

Initially, a corral (hog ranch) was created in Guanajay, which is mentioned for the first time on 21 July 1623, as listed in the Compendium of land grants, or rather Index in alphabetical order of the grants awarded by the Havana City Council, where, in granting Gaspar Pérez Borroto the Tahajaguas or Las Virtudes, San Andrés and San Marcos sites, it is indicated that they are located next to the Guanajay and Javaco corrals2.

In the structure of this toponym, the morphemes guana and jay can be distinguished. The former means ‘land’, ‘place’, as explained in a previous work3. The presence of the latter is frequent in toponyms that come from the Island Arawak, where it appears written in different forms (jay, jai, hay, hai): Guajaibón (culminating point of the Guaniguanico mountain range at 700 metres high); Damajayabo (river that rises in the Gran Piedra mountain range, in Santiago de Cuba); Guamuhaya (mountains in the central region of Cuba); Yaguajay (municipality in the province of Sancti Spíritus with mountainous relief in its centre, and also a hill in the heights of Maniabon, in Holguín); Jaibo (river that rises in the Nipe-Sagua-Baracoa mountains).

Likewise, this morpheme is present in the toponym Haiti, about which the chronicler Peter Martyr D’Anghera wrote: “But Haiti means roughness in their ancient language, and so they called the whole island Haiti […] because of the rough appearance of its mountains and the black thickness of its forests, and its frightening and dark valleys because of the height of the mountains…”4. To which can be added the following comment by Pedro Henríquez Ureña (quoted by José Juan Arrom): “Name of the highest peak in the ancient mountainous region of Cibao, according to Las Casas (Apologética… chaps. 6 and 197) …, from which ‘the whole island was named and called’. The peasants still call the mountains haitises“5.

In the analysis of a sample of 20 words that entered Spanish from the Island Arawak (language spoken by the aborigines of the Greater Antilles) and 15 Lokono words with the morpheme ha in their structure, it was found that in the referents the characteristics of: ‘hang’, ‘sting’, ‘prick’ and ‘hit’ are repeated. All these actions share a common feature, they are generated by physical entities that have two ends, one fixed and one free. It can also denote movement or displacement in a particular direction or be used figuratively (see Tables 1 and 2 in Appendix). Note the relation of ‘sting’, ‘prik’ and ‘hit’ to the term ‘rough’ (asperitas in the original Latin) used by Peter Martyr D’Anghera when translating the meaning of Haiti6.

For its part, the intrinsic meaning of the phoneme /i/ in Lokono implies that time remains unchanged, contracted at a single point, in the infinitely small, and is sometimes translated as ‘here’, as C.H. de Goeje explains7.

Although the direction between one end and the other of the entity denoted by the morpheme ha can be any, when the phoneme /i/ is added to the expression, which contracts the action to a single point, ‘here’, there is only one possible direction, the vertical. Note that a mountain or elevation can be described as a physical entity with a fixed end (on the ground) and a free end (the summit) extending vertically.

There is also a kinship between the Island Arawak morpheme jay (hay) and the Lokono word ayo, which means ‘up’ and “encodes the direction on the vertical dimension” as Rybka explains in his work The linguistic encoding of landscape in Lokono8. For example, C. H. de Goeje refers to: aiomun, ‘a high place’, ‘heaven’9. The absence in these Lokono words of the initial /h/ phoneme present in the Island Arawak morpheme hay can be explained by the fact that its use seems to be optional or depends on the context in which it is used. C. H. de Goeje cites numerous examples of the same Lokono words written with and without /h/ by different authors10.

From the above elements, we consider that the Island Arawak morpheme jay (also jai, hay, hai) means ‘high’, ‘elevated’, ‘up’, ‘above’.

Thus, guana, ‘place’, ‘land’ + jay, ‘high’, ‘elevated’, ‘above’ = guanajay, ‘upland’, ‘highland’.

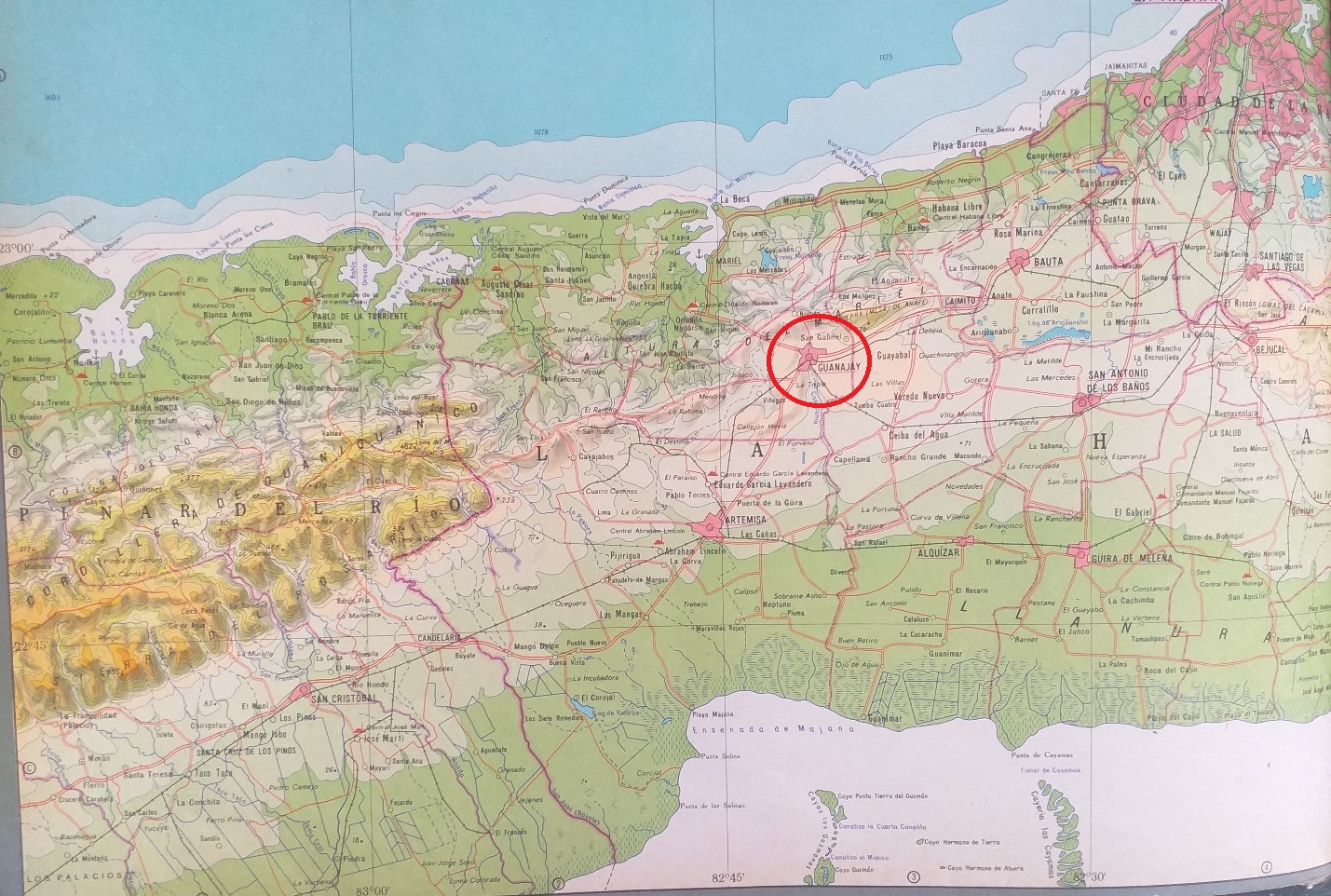

The city of Guanajay is located at an altitude of 100 meters above sea level11, very close to the heights of Mariel and Mesa de Anafe (275 meters high), geographical features located to the north and northeast of Guanajay, respectively, as well as in the vicinity of the mountain range Sierra de los Órganos, located to the west (Figure 1).

For the Arawaks who lived in the low, marshy areas of the southern Havana-Matanzas plain, the relief of Guanajay and its surroundings presented a marked contrast. This must have been perceived, for example, by the inhabitants of the aboriginal settlement of Guanimar, located south of Guanajay in a marshy area along the coast. For them, the Guanajay region was indeed an ‘upland’, a ‘high place’.

Figure 1

Location and relief of Guanajay

Even in areas where there is not a great difference in altitude, when the different terrain characteristics give rise to different ecosystems, with implications for the aboriginal way of life, places slightly higher than lowlands may have the morpheme jai in the structure of their Island Arawak names, as in the case of Jaimanitas (a village in the west of Havana, adjacent to the Hemingway marina, the latter built on a low site formerly occupied by mangroves) or Jaiguán (an old corral adjacent to Guanabo, in the area between Batabanó and Cajío, Artemisa province).

Finally, there is also the toponym guanajayabo, the name of a locality where a cattle ranch was created in 1559 and later a town was founded, currently called Máximo Gómez, in the province of Matanzas. The structure of the word includes the segments guanajay and abo. The latter, according to C. H. de Goeje explains that in Lokono it has the meaning of ‘appearance in space’ with the acceptations of ‘with’, ‘next to’, ‘on’, ‘in’14. On the use of this word in the Island Arawak, José Juan Arrom refers:

… If they found a small hill of jobos (Spondias mombin), using the abundant suffix abo, they called it job-abo, ‘The Jobo Grove’, if of güiras (Crescentia cujete), Güir–abo ‘The Güira Grove’, if of mayas (Bromelia pinguin), May–abo ‘The Maya Shrubbery and if of yayas (Oxandra lanceolata), Yay–abo ‘The Yaya Grove’.

In an explanatory note, Arrom adds: “Actually abo is a quasi-preposition equivalent to ‘with’, ‘collection of’. Jobabo can also be translated as ‘The Jobos“15.

So, guanajay, ‘upland’, ‘highland’ + abo ‘abundant suffix’ = guanajayabo, ‘The Heights’.

The town of Máximo Gómez (Guanajayabo) is located at an altitude of 20 metres, although nearby is the hill of La Industria, 74.5 metres high, and to the northeast there are other elevations with heights between 50 and 114 metres. This entire sector is located to the south of an extensive low coastal area known as Majaguillar Swamp (see figure 2). The difference in elevation and ecosystem type motivates the name.

Figure 2

Location and relief of Guanajayabo and Majaguillar Swamp

Several of the toponyms with the morpheme jay in their structure examined in this paper (Guanajay, Guanajayabo, Jaiguán, Jaimanitas) clearly originated in aboriginal communities settled in lowlands occupied by mangrove swamps, which provided a favourable environment for fishing, hunting and gathering. From the perspective of the residents in these areas, places that otherwise would hardly have been considered “uplands” were distinguished as such.

The peoples living in these environments were pre-tribal appropriators from the Middle Period, also known as Ciboney, who started arriving in Cuba from South America about four thousand years ago16. They were subsequently assimilated by the agro-pottery people, who arrived in Cuba some 1,300 years ago17, without traces of a process of retoponymisation in the form of geographical names that differed in structure and phonology. In this sense, the results of the linguistic analysis presented in this article constitute a new evidence that the Ciboney originally spoke an Arawak language, which confirms the statements of Sergio Valdés Bernal, Felipe Pichardo Moya and Alina Camps Iglesias, on the unity of the indigenous toponymic scheme of Cuba18.

It is also interesting that Peter Martyr D’Anghera pointed out that Haiti is a name corresponding to the “ancient language” of the aborigines. Previously, he had indicated that both Haiti and Quisqueya were “the names that the first inhabitants gave to Hispaniola “19. The possibility cannot be excluded that these “first inhabitants” belonged to Arawak communities that arrived in migratory waves prior to the aboriginal agro-pottery settlers, and that the aboriginal toponymy of the neighbouring island was under the influence of historical and linguistic processes similar to those we have described for Cuba.

Appendix

Table 1

Selection of words that entered Spanish from the Island Arawak with the morpheme ha in their structure, their referents, sources and possible associated characteristic.

| Island Arawak | Referent | Source | Possible characteristic associated with the morpheme ha |

| Material culture | |||

| Hamaca | Hammock | Pichardo (1875, p. 190) | Hang |

| Jaba | Basket | Pichardo (1875, p. 202) | Hang |

| Jabuco | Narrow mouth basket | Pichardo (1875, p. 203) | Hang |

| Jagüey | Pond, Cistern | Pichardo (1875, p. 204) | Hang (to draw water) |

| Fauna | |||

| Jaguey | Mosquito | Pichardo (1875, p. 204) | Sting |

| Jajabí | Species of parrot | Bachiller (1883, p. 309) | Sting (Peck) |

| Flora | |||

| Jabiya | A type of liana | Pichardo (1875, p. 202) | Hang (of trees) |

| Jairel | A type of liana | Bachiller (1883, p. 308) | Hang |

| Jayún | A type of rush | Pichardo (1875, p. 207) | Hang (from it hang the roots of algae in bogs and rivers) |

| Jabí | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 202) | Hang (flowers, fruits, aerial roots, etc. can hang from trees. For example, the aerial roots of the jagüey hang looking for the ground and transform into stems)

Prick. Some trees and shrubs may have thorns. |

| Jagua | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 203) | |

| Jagüey | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 204) | |

| Jagüilla | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 204) | |

| Jaimiquí | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 205) | |

| Jaragua | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 206) | |

| Jata | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 206) | |

| Jatía | A type of tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 206) | |

| Jayabacaná | A type of thorn tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 206) | |

| Jagua-jaguita | A type of thorn tree | Pichardo (1875, p. 203) | |

| Jaguay | A type of bush | Pichardo (1875, p. 204) | |

Sources: Pichardo, 187520 and Bachiller, 188321.

Table 2

Selection of Lokono words with the morpheme ha in their structure, their referents, sources and possible associated characteristic.

| Lokono | Referent | Source | Possible characteristic associated with the morpheme ha |

| Material culture | |||

| Hamaka | Hammock | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Hang |

| Hábba | Basket | Moravian D. (1883, p. 114) | Hang |

| Harharo | Wooden spoon to stir the casserole | Pate (2011, p. 90) | Hang |

| Hadisa | Grater to grate and sift the cassava | Pate (2011, p. 86) | Prick |

| Haropona | Spear | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Prick |

| Haku | Mortar | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Hit |

| Fauna | |||

| Haniju | Fly | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Sting |

| Hánuba | Strong stingin fly | Moravian D. (1883, p. 116) | Sting |

| Flora | |||

| Haiali | A type of liana | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Hang |

| Haliti | Sweet potato (the plant is a type of liana) | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Hang |

| Haiawa | A type of tree | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Hang (flowers, fruits, aerial roots, etc. can hang from trees) |

| Hákkia | A type of tree | Moravian D. (1883, p. 115) | Hang |

| Haharo | Wild pineapple | Pate (2011, p. 87) | Prick |

| Otros | |||

| Hatta | Stick | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Stick |

| Hau | Lazy, flaccid | de Goeje (1928, p. 23) | Hang (metaphor) |

Sources: Moravian Dictionary, 188322, Goeje, C.H. de, 192824 and Patte, M.F., 21123.

Notes

- Roig de Leuchsenring, Emilio. 1937. Actas capitulares del ayuntamiento de La Habana [Chapter Acts of the Havana City Council]. I. Vol. II. Page 157.

- Bernardo y Estrada, Rodrigo. 1858. Prontuario de mercedes, o sea Índice por orden alfabético de las mercedes concedidas por el excmo. Ayuntamiento de La Habana [Compendium of land grants, or rather Index in alphabetical order of the grants awarded by the Havana City Council]. Page 96.

- Celeiro Chaple, Mauricio. 2023. Arawak Mysteries in the Spanish Spoken in Cuba: Guana. www.laotraraiz.cu

- Peter Martyr D’Anghera. 1892. “Décadas del nuevo mundo” [“Decades of De Orbe Novo”]. In Fuentes históricas sobre Colón y América. T. II. Pages 384-385.

- Arrom, José Juan. 2011. “El nombre de Cuba: sus vicisitudes y su primitivo significado” [“The Name of Cuba: its Vicissitudes and its Primitive Meaning”]. In José Juan Arrom y la búsqueda de nuestras raíces. Oriente Publishing House and García Arévalo Fundation. Page 47.

- Martyris ab Angleria, Petri. 1530. De Orbe Novo. Compluti apud Michaelē d Eguia. Tertie decadis. Caput septimum. Fol. XLVIII. Archive.org.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. The Arawak Languaje of Guiana. Cambridge University Press. Page 49. cambridge.org.

- Rybka, K. A. 2016. The Linguistic Encoding of Landscape in Lokono. LOT. Utrecht. Pages 119-122. https://www.researchgate.net.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. cit. Page 115.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. cit. Page 150.

- Núñez Jiménez, Antonio, et. al. Diccionario geográfico de Cuba [Gazetter of Cuba]. 2000. Havana.

- Rybka, K. A. 2016. cit. Page 98.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. cit. Page 149.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. cit. Pages 108, 141.

- Arrom, José Juan. 2011. “Aportaciones lingüísticas al conocimiento de la cosmovisión taína” [“Linguistic Contributions to the Knowledge of the Taino Worldview”]. In José Juan Arrom y la búsqueda de nuestras raíces. Oriente Publishing House and García Arévalo Fundation. Page 96.

- Pérez Carratalá, Alfredo and Izquierdo Díaz, Gerardo. 2014. “Cuba: Migración e intercambio socio cultural en el Caribe” [“Cuba: Migration and Socio-Cultural Exchange in the Caribbean”]. In Los indoamericanos en Cuba. Estudios abiertos al presente. Coordinator Felipe de Jesús Pérez Cruz. Social Sciences Publishing House. Havana. Page 66.

- Etayo Torres, Daniel. 2006. Tainos: mitos y realidades de un pueblo sin rostro [Tainos: Myths and Realities of a Faceless People]. Asesor Pedagógico Publishing House. page 36. www. cubaaqueologica.org.

- Valdés Bernal, Sergio. “La conquista lingüística aruaca de Cuba” [“The Arawak linguistic conquest of Cuba”]. In Revista de la Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba José Martí. Year 104, No. 1, Pages 161-179.

- Peter Martyr D’Anghera. 1892. cit. T. II. pages 384-385.

- Pichardo Esteban. 1875. Diccionario provincial casi razonado de vozes y frases cubanas [Almost reasoned provincial dictionary of Cuban words and phrases]. Fourth Edition. Havana.

- Bachiller y Morales, 1883. Antonio. Cuba primitiva [Primitive Cuba]. Havana.

- Moravian Brothers. 1882. Arawakisch-Deutches Wörterbuch, Abschrift eines im Besitze der Herrnhuter Bruder-Unität bei Zittau sich befindlichen-Manuscriptes. In Grammaires et Vocabulaires Roucouyene, Arrouague, Piapoco et D’autre Langues de la Région des Guyanes, par MM. J. Crevaux, P. Sagot, L. Adam. Paris, Maisonneuve et Cie, Libraries-Editeurs. https://books.google.com.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. cit.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. La langue arawak de Guyane, Présentation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français-arawak. IRD Éditions. Marseille. https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr.

REGISTERED WITH THE NATIONAL CENTRE FOR COPYRIGHT (CENDA)