Introduction

Guana is a segment present in the structure of several words from the Spanish language spoken in Cuba that come from the language of the aborigines (Taino, also known as Island Arawak) and is also found in numerous place names. In this article we present the results of the research on the etymology of these words, without including the toponyms, which will be dealt with independently in other works.

Seven words from the Spanish language spoken in Cuba with the segment guana in their structure were included in the analysis; of these, four phytonyms and three zoonyms (table 1).

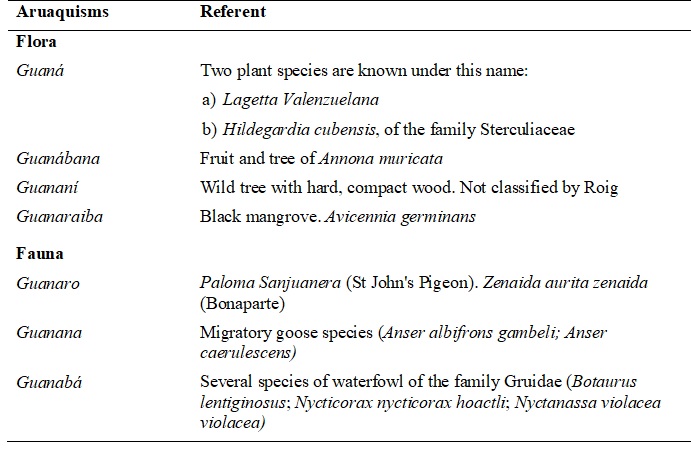

Table 1

Words of the Spanish language spoken in Cuba that come from the Island Arawak language and have the segment guana in their structure, grouped by lexical fields and with their referents. Taken from Valdés Bernal, 19911.

The Royal Spanish Academy, in its Dictionary of the Spanish Language (2014), includes two of these words with the segment guana in their structure: guanabá and guanábana, without identifying them as words that come from the Island Arawak language.

Sources used include chroniclers of the Indies and scribes; lexicographers from Cuba, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico; and dictionaries, grammars and studies on the Lokono, also known as Arawak Language of the Guianas.

The methods applied were: the comparative study of the Island Arawak and Lokono, and deductive reasoning based on the information provided by the descriptive character of the naming pattern common to both languages.

Island Arawak and Lokono can be considered dialects of the same language, due to their lexical and morphological correspondences3. Regarding the descriptive character of the naming pattern of these languages, the scholar C.H. de Goeje says: “an Arawak word is a description of a few characteristics of the thing”.4 This peculiarity makes it possible to find clues to the meaning of words from the characteristics of their referents.

Guanaro

The Cuban lexicographer Esteban Pichardo describes the Paloma Sanjuanera (St John’s Pigeon), Zenaida aurita (figure 1), as follows:

It is smaller than the Wood Pigeon; although stocky, ashen in colour, turning slightly wine-coloured; it feeds on seeds; it lays two white eggs high up in the trees, making its nest with a regular curiosity of dry sticks in May and June; its song is lugubrious and plaintive; it is not so common as far as Saint John’s Day, from where it gets its name; but in the Vueltarriba (region in western Cuba) it retains the indigenous name of Guanaro, the male, and Guanara, the female5.

Figure 1

St John’s Pigeon, Zenaida aurita

The lexicographers Zayas6 and Rodríguez Herrera7 record guanara with the phoneme /a/ at the end.

Before analysing the relationship between this word and its referent, we must examine a very valuable observation in the An Account of the Antiquities of the Indians, book written by the friar Ramón Pané, commissioned by Christopher Columbus to study the beliefs and religious practices of the aborigines, who lived among them for several years and learned some of their language:

They say that while Guahayona was in the land where he had gone, he saw that he had left a woman in the sea, which gave him great pleasure, and he immediately sought out many lavatories to wash himself, because he was full of those sores that we call French disease. She then put him in a guanara, which means a secluded place, and there he was healed of his sores. She then asked him for permission to go on her way, and he gave it to her. This woman was called Guabonito (emphasis added)8.

The above elements indicate that the original Island Arawak word was guanara, and that its passage into Spanish as guanaro is due to the use of the gender-flexive suffix -o to distinguish the sex of the specimens of the animal species.

In the structure of the word guanara, the segments guana and –ra can be distinguished. From the fragment quoted from Pané, we can hypothesise that guana means ‘place’ and the suffix -ra gives the meaning of ‘secluded, apart’.

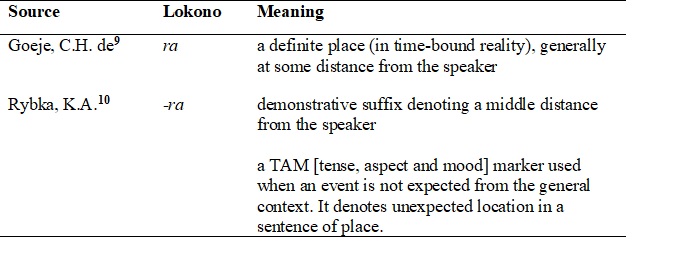

In Lokono there is also the suffix -ra and its meaning in that language is shown in table 2.

Table 2

Meanings of -ra in Lokono

As can be seen, the suffix -ra, means ‘at a middle distance’, ‘unexpected location’, where, in addition to the distance at which the place is located, its private character is emphasised, all of which coincides with Pané’s translation of ‘secluded, apart’ for the cognate in the Island Arawak.

Regarding the segment guana, it is possible to identify a non-identical cognate in the structure of the lokono word wunabu, ‘(at) the ground’, ‘below’11. In this word, wuna has the meanings of ‘ground, soil’ and abo means in this case ‘by, on, in’12. We can also find this non-identical cognate in the lokono word wunapu, ‘(to) the ground’13.

In Lokono there is another word (ororo / hurruru) which has the same meanings of ‘ground, soil’14 and also includes those of ‘land, farm, country, world’15. We consider that in the Northern Proto-Arawak which gave rise to Lokono and the Island Arawak, all these meanings were denoted by the word wana / guana, which continued to be used for this purpose in the Island Arawak, unlike Lokono, as shown in Pané’s fragment quoted above, as well as several lokonos words naming animals, plants and mythical beings, where the form wana has been preserved “fossilised” (see table 3).

Table 3

Lokono words with the segment wana

The etymology of the first two examples in Table 2 will be explained below. It is noteworthy that the Lokono word Wánnana is an identical cognate of the Island Arawak Guanana. Wanania, on the other hand, could be a non-identical cognate of Guananí.

Thus, in Island Arawak, guana, ‘land, place’ + -ra, ‘middle distance, unexpected location’ = guanara, ‘secluded place’.

According to Esteban Rodríguez Herrera (quoted by José Juan Arrom), the word Guanara has been preserved in parts of Cuba as the name of a pigeon that lives in secluded forests22. This tendency to hide deep in the forest (a “secluded place”) is the characteristic that gave rise to the pigeon’s Island Arawak name.

Guanaraiba

Guanaraiba is a species of tree also known as Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans).

Mangroves make up extensive areas of coastal forests located in the tropical and subtropical zones of the planet23. In Cuba they occupy 5% of the country’s surface area24, a proportion that was undoubtedly higher before the Spanish conquest. There are four main tree species that make up mangrove forests: Rhizophora mangle (Red mangrove), Avicennia germinans (Black mangrove), Laguncularia racemosa (Patabán) and Conocarpus erectus (Yana). The latter species is classified as pseudo mangrove or peripheral species25.

The Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans) is generally located behind the first fringe of Red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) that occupies the shoreline of the Coastal plain. While the Red mangrove grows on stilt roots that intertwine and form a barrier that is difficult to pass through, the Black mangrove has subterranean roots that produce cylindrical structures called pneumatophores that rise up in the water around the tree and cover the mangrove floor (see figure 2).

Figure 2

Red mangrove, Rhizophora mangle and Black mangrove, Avicennia germinans

B. Black mangove. Avicennia germinans. Photo: Codiferous from Wikipedia BY-SA 3.0

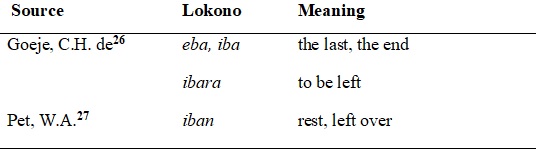

In the structure of the Island Arawak word, the segments guanara and iba can be distinguished. We already know the meaning of the former, and as for the latter, its meanings in lokono and that of some derived words are presented in table 4.

Table 4

Meanings of iba and some derivative words, in lokono

Therefore, guanara, ‘secluded place’ + iba ‘end’ = guanaraiba, ‘end of the secluded place’.

The aboriginal fisher-hunter-gatherer communities, as well as the agro-potters, used the mangrove swamp as a food-generating area, as Veloz Maggiolo points out in reference to the former:

The mangrove roots are home to millions of juvenile fish that take refuge in the area; it is an important breeding ground for oysters and oyster-like bivalves; the marshy areas provide a very positive habitat for crustaceans of various species, while the mangrove canopy is a nesting site for a variety of seabirds. Linked to the sea and the river, the mangrove is the ideal harvesting site: it produces natural proteins all year round, attracts terrestrial animals in the more potable areas of its brackish waters and maintains a level of animal reproduction that is difficult to surpass or deplete by a band of 30 to 100 people28.

In relation to the exploitation of the mangrove swamp by the agro-potters, researchers Pedro P. Godo and Milton Pino point out: “The late agro-pottery communities, commonly referred to as Taino and Subtaino in our texts, also took advantage of mangrove resources depending on the location of their settlements, close to the coast and their settlement systems”. These authors relate archaeological data from sites and residues corresponding to these cultures that show agriculture strongly complemented by marine resources, including those from mangroves29.

For that reason, the mangrove swamps were common places for aboriginal activities, such as fishing, gathering oysters and other molluscs, hunting for hutia and various other activities. If they wanted to reach the mainland from the sea, they had to cross the tangle of stilt roots of the Red mangrove, until they reached the part of the coastal plain where the Black mangrove grows and the most difficult part of the journey, far from the mainland, ends. It is the ‘end of the secluded place’.

Guanana

This word, which comes from the Island Arawak, names two species of migratory geese: Guanana (Anser albifrons gambeli) and Black Guanana (Anser caerulescens). The Black Guanana is found in the wild in two different plumage stages. In one of these it is almost completely white. In the other phase, from which it derives its name, it has a bluish-brown plumage on the body30. Previously identified as distinct species, they were found to be forms of the same species, determined by plumage genes (see figure 3).

Figure 3

Guanana species

B. Black Guanana. Anser caerulescens. Photo: Ecured.cu

It is revealing that in Lokono the same word is used to name the Guanana (or some other species of goose) as in the Island Arawak, as the Moravian Brothers’ dictionary attests: Wánnana, ‘a goose’ (eine Gans). This finding also confirms that in the Northern Proto-Arawak, which gave rise to Lokono and Island Arawak, the land was named in the same way (wana / guana).

The chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, in a famous passage included both in his Summary of Natural History of the Indies published in 1526 (chapter VIII)33, and in the first part of the General and Natural History of the Indies of 1535 (book XVIII, chapter II)34, relates how the aborigines of Jamaica and Cuba hunted Guananas, xxxx, and then they hid under one of them, until a bird landed on the “gourd”, grabbed it by the legs and drowned it under the water.

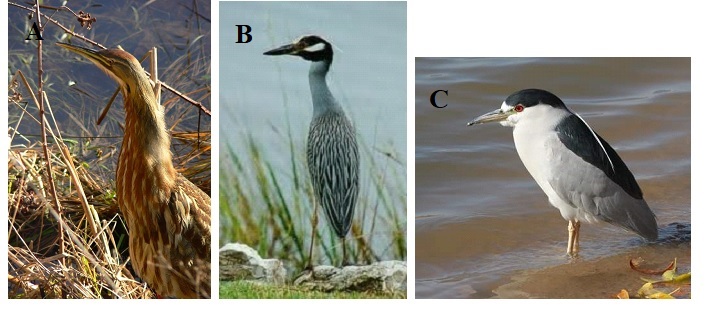

Guanabá

As Valdés Bernal points out, this name is used for several species of waterbirds belonging to the gruid family (Botaurus lentiginosus; Nycticorax nycticorax hoactli; Nyctanassa violacea violacea) (see figure 4).

All three species winter in the Cuban archipelago and do not breed in the country. In the case of the Florida Guanabá, some individuals may remain year-round in Cuba35.

Figure 4

Guanabá species

B. Royal Guanabá. Nyctanassa violacea. Photo: Ecured.cu

C. Florida Guanabá. Nyctocorax nyctocorax hoactli. Photo: Ecured.cu

Let us look at the meanings of the suffix -ba in Lokono, which are presented in table 5.

Table 5

Meanings in lokono of suffix -ba

Note that the difference between the two meanings of -ba is that one expresses spatial movement and the other temporal movement (the repetition is a second action removed from the first in time). This confirms C. H. de Goeje’s observation that “the Arawaks do not distinguish between time and space in the way we do “38.

Thus, guana, ‘place’, land’ + -ba, ‘moves away’, ‘again’ = guanabá, ‘goes to another land’, ‘goes to another place’, describing the characteristic of Guanabá to migrate at a certain time of the year.

The difference between the motivation for the name Guanana and Guanabá seems to lie in the fact that, in the first case, the flocks of migrating birds are very visible (they fly in large inverted V formations) and it is clear that they come from other lands, that some birds stay in Cuba and others continue their journey. In short, the lands they inhabit are multiple. In the case of the Guanabá, their migratory flight might not be so evident and the truth for our aborigines was that they went to another place at a certain time of the year.

Guanábana

The guanabana (soursop) is a tree of the Annona muricata species that attracted the early attention of the Spanish conquistadors. Peter Martyr D’Anghera, Fernández de Oviedo and Bartolomé de las Casas mention it in their chronicles.

The fruit of the soursop is used to make a delicious drink known as champola. It has an oval shape (see figure 5) and in some fruits irregular and curved.

Figure 5

Guanabana (soursop) fruit

The Lokono also know this plant, native to tropical America and the Caribbean, and call it kayedi and also sorosaka39. The first name means in Lokono ‘with necklace’40 and seems to be motivated by the soft spines that cover the shell of the fruit, reminiscent of the necklaces made of wild animal teeth used in ancient times by the Lokono41 and the second, ‘sucking bag’42. These names indicate that it is the fruit of the Anonna muricata plant that most attracts the attention of the Lokonos, to the point of giving it its name, and suggest that in the Island Arawak it is also the fruit that motivates the name.

The American linguist Taylor also refers to Oarafana as a Lokono name for Annona Muricata43. Kouwenberg considers it to be a non-identical cognate of the Island Arawak Guanábana44.

The Lokono word bana has three meanings: ‘surface’, ‘leaf’, ‘liver’45. Since the shape of the soursop can resemble a liver, we believe that this meaning corresponds to the Island Arawak word.

Thus, guana, ‘earth’ + bana, ‘liver’ = guanábana, ‘liver of the earth’.

The Moravian dictionary records the Lokono word wanassuru, which is the name of the “trumpet tree”, a plant of the genus Cecropia, to which the Yagruma belongs. C. H. de Goeje records it as uanasoro and classifies it as of “uncertain (etymological) origin”46; however, in its structure we can distinguish the morphemes wana and ssuru / soro. The first one is a cognate of the Island Arawak guana, which is another evidence that in the Northern Proto-Arawac that gave rise to Lokono and Island Arawak there was this word. The second Lokono word means ‘to suck’, ‘flow’47, so wana, ‘earth’ + ssuru, ‘to suck, flow’ = wanassuru, ‘suck from the earth’, ‘flow from the earth’.

The internodes of the stems and branches of the species of the genus Cecropia are hollow and contain a toxic latex, characteristics that seem to motivate the Lokono name.

The metaphor “sucks from the earth” is reminiscent of that of “liver of the earth” and shows that such similes are possible in the Arawak languages.

Interestingly, the green fruit and the aqueous extract of the leaves of Annona muricata have hepatoprotective properties and are effective against jaundice48. It is likely that the Arawak people used the plant for these purposes, given its availability in the area they inhabited and the tradition of using the flora for medicinal purposes. However, we can only conjecture whether they were aware of the relationship between jaundice and the liver and whether this also influenced the motivation for the name of the plant and the fruit.

Guaná

The linguist and researcher, Sergio Valdés Bernal, refers to the word guaná:

Name given in western Cuba to a plant known in the eastern provinces as “Daguilla“, of the species Lagetta valenzuelana, of the family of Thymeliaceae, whose bast provides very resistant white textile material. There is also another species of Guaná, classified by Roig and Mesa (1928) as Hildegardia cubensis, of the Sterculiaceae family49.

In addition to the form of the word accented in the last syllable, the form stressed on the penultimate syllable, guana, is also recorded by the lexicographers Pichardo50 and Suárez51.

The two tree species known as Guaná, Lagetta valenzuelana and Hildegardia cubensis, are endemic to Cuba52. It is precisely this characteristic that motivates their Island Arawak name. The Arawak-speaking peoples, upon their arrival in Cuba, observed these previously unknown trees and, instead of selecting some physical characteristic to name them, they did so by referring to them as ‘from the place’, ‘from the land’, using the word guaná.

Guananí

Valdés Bernal explains that Guananí is the name applied in Cuba to a wild tree with hard, compact wood, and that today we do not know which tree it was53. Pichardo adds that the wood is fine-grained and light yellow in colour54.

The fact that the species of this tree is unknown makes it risky to make an etymological proposal, as it is difficult to link its name to the characteristics of the referent and to reach conclusions about their relationship. Therefore, we refrain from making proposals on the etymology of this word.

Discussion

The results achieved show the effectiveness of the combined use of the selected research methods to determine the etymology of the Island Arawak words that have passed into Spanish.

They also provide information on the hitherto uncertain etymology of some Lokono words, such as wánnana and uanasoro. These findings confirm the close phylogenetic relationship between Island Arawak and Lokono, and demonstrate that the comparative study of the two languages could also be used to investigate the evolution of Lokono.

Of the three main roots of Cuban nationality, it was the aboriginal root that transferred knowledge about the country’s nature to the others and to the Creole descendants that they gave rise to. This is an undervalued contribution that includes knowledge related to agriculture, food, house building, natural medicine, fishing and forest exploitation, among other aspects, without which it would have been difficult to survive in the first centuries after the conquest, and which characterised the peasants, who until the 20th century constituted the majority of the population, to a greater extent. Even today, this knowledge still contributes to daily life.

The aboriginal names of animal and plant species that have passed into the Spanish spoken in Cuba, including those examined in this article, are also evidence of this legacy.

Notes

- Valdés Bernal, Sergio. 1991. Las lenguas indígenas de América y el español de Cuba [The indigenous languages of the Americas and the Spanish of Cuba]. Editorial Academia, La Habana.

- Real Academia Española. 2014. Diccionario de la lengua española [Spanish language dictionary]. Vigésimo tercera edición. www.rae.es

- Kouwenberg, Silvia. 2010. Taino´s linguistic affiliation with mainland Arawak. En Proceedings of the twenty-second congress of the International Association for Caribbean Archaeology (IACA). The Jamaica National Heritage Trust.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. The Arawak Language of Guiana. Cambridge University Press. www.cambridge.org. Page 236.

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1875. Diccionario provincial casi razonado de vozes y frases cubanas [Almost reasoned provincial dictionary of Cuban words and phrases]. Cuarta Edición. La Habana. Page 277.

- Zayas, Alfredo. 1914. Lexicografía Antillana: diccionario de voces usadas por los aborígenes de las Antillas mayores y de algunas menores y consideraciones acerca de su significado y de su formación [Antillean Lexicography: a dictionary of the voices used by the aborigines of the Greater Antilles and some lesser Antilles and considerations about their meaning and formation.]. La Habana. Page 260.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1990. Notas, mapas y apéndices a la nueva versión de la Relación acerca de las antiguedades de los indios de Fray Ramó Pané [Notes, maps and appendices to the new version of the friar Ramón Pané’s, An account of the antiquities of the indians]. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, La Habana. Page 64.

- Pané, Ramón. 1990. Relación acerca de las antigüedades de los indios. Nueva versión con notas, mapas y apéndices por José Juan Arrom [An account of the antiquities of the indians. New version with notes, maps and appendices by José Juan Arrom]. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, La Habana. Page 27.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Page 143.

- Rybka, K. A. 2016. The Linguistic Encoding of Landscape in Lokono. LOT. Utrecht. https://www.researchgate.net. Pages 63, 98, 145-146.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Pages 35, 111, 120.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Page 108.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Pages 35, 111.

- Patte, M. F. 2011. La langue Arawak de Guyane. Preséntation historique et dictionnaires arawak-français et français-arawak [The Arawak Language of French Guiana. Historical presentation and Arawak-French and French-Arawak dictionaries]. IRD Éditions. Page 98.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Pages 38, 166.

- Moravian Brothers. 1882. Arawakisch-Deutches Wörterbuch, Abschrift eines im Besitze der Herrnhuter Bruder-Unität bei Zittau sich befindlichen-Manuscriptes [Arawak-German Dictionary]. In Grammaires et Vocabulaires Roucouyene, Arrouague, Piapoco et D’autre Langues de la Région des Guyanes, par MM. J. Crevaux, P. Sagot, L. Adam. Paris, Maisonneuve et Cie, Libraries-Editeurs. http://books.google.com. Page 164.

- Moravian Brothers. 1882. Op.cit. Page 164.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. Op.cit. Page 226.

- Bennett, John Peter. In Patte, Marie France. 2011. Op.cit. Page 225.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Pages 33, 200.

- Goeje, C. H. de. 1939. Nouvel examen des langues des Antilles: avec notes sur les langues arawak-maipure et caribes et vocabulaires shebayo et Guayana (Guyane) [New examination of the languages of the West Indies: with notes on the Arawak-Maipure and Carib languages and Shebayo and Guayana vocabularies.]. In Journal de la Société des américanistes, Nouvelle Série, Vol. 31, No. 1 (1939), pp.1-120. Published by: Société des Américanistes. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24601998. Page 7.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1990. Op.cit. Page 64.

- Leda Menéndez, José M. Guzmán y Ángel Priego. 2006. “Manglares del Archipiélago Cubano: aspectos generales” [Mangroves of the Cuban Archipelago: general aspects]. In Ecosistema de manglar en el Archipiélago Cubano Estudios y experiencias enfocados a su gestión. Editorial Academia. La Habana. Page 15.

- Leda Menéndez, José M. Guzmán y Ángel Priego. 2006. Op.cit. Page 17.

- Leda Menéndez, José M. Guzmán y Ángel Priego. 2006. Op.cit. Page 21.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Pages 15, 68, 145.

- Pet, Willem J. A. 2011. A Grammar Sketch and Lexicon of Arawak (Lokono Dian). SIL e-Books. Page 135.

- Veloz Maggiolo, Marcio. 1980. Las sociedades arcaicas de Santo Domingo [The Archaic Societies of Santo Domingo]. Museo del Hombre Dominicano y Fundación García Arévalo. Santo Domingo. Pages 34-35.

- Godo, Pedro P. y Pino, Milton. 2006. “Sociedades aborígenes de Cuba: sistemas de asentamiento y economía del manglar” [Aboriginal societies in Cuba: settlement systems and mangrove economy]. En Ecosistema de manglar en el Archipiélago Cubano. Estudios y experiencias enfocados a su gestión. Editores científicos: Leda Menéndez Carrera y José Manuel Guzmán Menéndez. Editorial Academia. La Habana.

- El zoologico electrónico [The electronic zoo]. www.damisela.com/zoo/ave/otros/anser/anatidos/gansos/caerulescens/index.htm.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Page 35.

- Rybka, K. A. 2016. The Linguistic Encoding of Landscape in Lokono. LOT. Utrecht. https://www.researchgate.net. Pages 63, 98.

- Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo. Sumario de la Natural Historia de las Indias [Summary of the Natural History of the Indies]. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México – Buenos Aires. www.HistoriaDelNuevoMundo.com.

- ————————————– 1853. Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierra-firme del mar océano [General and Natural History of the Indies, the Islands and the Land-locked Ocean.]. Real Academia de Historia. Madrid. http://books.google.com

- Navarro, N. 2021. Lista anotada de las aves de Cuba [Annotated List of Cuban Birds]. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. Op.cit. Pages 26, 53.

- Pet, Willem J. A. 2011. Op.cit. Page 36.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Page 49.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. Op.cit. Pages 123, 203.

- Patte, Marie France. 2011. Op.cit. Page 235.

- About these necklaces, see Brett W. H. 1868. The Indian Tribes of Guiana. Their Condition and Habits. R. Clay, son and Taylor, Printers. London. https://books.google.com. Page 26 and the illustration “snake catcher” on the frontispiece of that work.

- Soro is a root present in Lokono words that denote the ways in which liquid flows are generated, such as: a-soroto, ‘to suck’; a-sorokodo, ‘to spill, to gush’; soropa, ‘syrup, molasses’, among others, while saka is a creole word, the result of contact with other languages, which means ‘bag’.SeeC. H. de Goeje, 1928, Pages 41, 156-157 and Patte, 2011, pages 191, 203.

- Quoted by Valdés Bernal.1991. Op.cit. Page 219 and Kowenberg, 2010. Op.cit Page 682.

- Kowenberg, 2010. Op.cit. Pages 680-682.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Page 107.

- Goeje, C. H. de.1928. Op.cit. Page 266.

- See note 42.

- Ortiz-Septién, Grecia y Campos-Ortiz, Sarahí. 2018. Propiedades curativas de las hojas de guanábana (Annona muricata) y su impacto potencial fármaco-industrial [Healing properties of soursop (Annona muricata) leaves and their potential pharmaco-industrial impact]. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas. https://icuap.buap.mx

- Valdés Bernal, Sergio. 1991. Op.cit. Page 218.

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1875. Op.cit. Page 174.

- Suárez, Constantino. 1921. Vocabulario cubano [Cuban Vocabulary]. La Habana. Página 261.

- Grupo de Especialistas en Plantas Cubanas – CSE/UICN. 2016. Lista roja de la flora cubana [Red List of Cuban Flora]. En Bissea, Boletín sobre Conservación de Plantas del Jardín Botánico Nacional de Cuba, Vol. 10. Número Especial 1. http://repositorio.geotech.cu/jspui/. Pages 232, 239.

- Valdés Bernal, Sergio. 1991. Op.cit. Pages 220, 221.

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1875. Op.cit. Page 176.