One of the most visible manifestations of the aboriginal legacy in the culture is found in the language. In Cuban Spanish there are hundreds of words with this origin that allude to objects, phenomena and concepts typical of the Cuban cultural and geographic environment, according to Cuban researcher and linguist Sergio Valdés Bernal1.

Despite the importance of this lexical legacy, the reason for the existence, meaning and form of most of these words is unknown, as well as the meaning and motivation of a large number of toponyms with the same origin that exist in Cuba, a reality that evidences the need for new studies on the subject.

The people who inhabited the island when the Spaniards arrived spoke a language belonging to the South American Arawak family, one of the most widespread on the continent before the European conquest. The variant of the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas is called Island Arawak or Taino.

In the structure of numerous words from this language that have entered the Spanish language it is possible to find the morpheme gua. It is frequent in any position: at the beginning, in the middle or at the end, and its reiteration caught the early attention of Europeans. The chronicler Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, in his Decades of the New World, published in 1516, notes: “Gua being the article in their language. There are very few of their names, particularly those of kings which do not begin with this article gua, such as Guarionex, and Guaccanarillus, and the same applies to many names of places”2.

For centuries, this was the grammatical function attributed to the Island Arawak morpheme gua. In 1883, Antonio Bachiller y Morales, in his work Cuba Primitiva, considered it a demonstrative3. In 1897, the Puerto Rican scholar Cayetano Coll y Toste, in his Prehistoria de Puerto Rico, estimated that gua, as a prefix was equivalent to the articles the, it, him; and as a suffix to the prepositions of, from4. In 1914, the Cuban lexicographer Alfredo Zayas, in his Lexicografía Antillana, also refers to Peter Martyr d’Anghiera and states that gua means the– the one who is. Further on he states: “at the end of the word it does not seem to be an article and on the other hand, this syllable gua enters in the formation of many words, without having that character or concept”5.

At the time the aforementioned authors made their observations on the morpheme gua, an important event had already occurred in the study of Island Arawak, which opened the way for a deeper knowledge of this language and, consequently, to establish the meaning of the aforementioned morpheme. In 1871, the American archaeologist, ethnologist and linguist, Daniel G. Brinton, published an article entitled The Arawak language of Guiana and its linguistic and ethnological relations, which demonstrated for the first time the relationship between the Lokono of the Guianas and the languages spoken by the aborigines of the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas6.

Since Lokono is still a living language (although in danger of disappearing) and there are dictionaries and grammars written by European navigators and missionaries between the XVI and XIX centuries, as well as modern studies developed by linguists, it is possible to study Island Arawak through the comparative method aimed at identifying lexical and phonetic similarities between the two languages. Several studies have shown that Island Arawak and Lokono are very similar and could even be considered dialects of the same language7. It is also possible to study Island Arawak by comparing it with other languages of the Arawak family.

However, Brinton failed to identify in Lokono the cognate (a word with the same etymological origin) of the Island Arawak morpheme gua and limited himself to pointing out that it is not an article, erroneously considering it a sign or indicator of the vocative8.

In 1939, Claudius Henricus de Goeje, a Dutch sailor and cartographer, who fell in love with the Arawak culture during an expedition to Suriname in the early 20th century and dedicated the rest of his life to study it, published in the Journal dela Société des Américanistes, his work Nouvel Examen des Langues des Antilles, where for the first time the Island Arawak morpheme gua is identified as a cognate of the Lokono wa, with the meaning of ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘our’9.

Previously, in 1928, C. H. de Goeje had published a work on Lokono, entitled The Arawak Language of Guiana, where he delves into the meanings of the morpheme wa in that language, which turn out to be diverse and not limited exclusively to ‘us’, ‘our’10. It is therefore striking that in his 1939 work, this author did not attempt to find other meanings of the morpheme gua in Island Arawak.

In 1970, the eminent Cuban pedagogue and researcher José Juan Arrom, published in the Bulletin of the Royal Spanish Academy an article entitled, Para la historia de las voces “conuco” y “guajiro”. In that work, the author rightly indicates that the word guajiro comes from the Island Arawak word guaxerí (recorded by Bartolomé de Las Casas) which means ‘our companion’, where the morpheme gua is cognate of the Lokono wa, ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘our’11. In later works Arrom, when analyzing other Arawak insular words, assigns the same meaning of ‘us’, ‘our’, to the morpheme gua, although not always such etymology is correct, as in the case of the anthroponym Guacar12 (one of the names attributed to the goddess Atabeira), where in reality it means ‘contracted’, in its meaning of ‘reduced to a smaller size’, as we demonstrated in a previous entry (Atabeira: the names of the goddess).

At present, there are no studies on the etymology of the words from Island Arawak that assign to the morpheme gua a meaning different from ‘we’, ‘our’ or those erroneous ones we have already mentioned. In this sense, the purpose of the present work is aimed at demonstrating the existence of words coming from this language where the morpheme gua is not used as a pronoun of the first person plural and has other meanings similar to those recorded by C. H. de Goeje for the Lokono cognate of this morpheme (wa).

C. H. de Goeje points out as the general meaning of this Lokono morpheme: “Oa or wa, stationary, separate among the events or things that partake in the passing of time”. As this author explains, the expression “events or things that partake in the passing of time” refers to events that may be passing or to a condition or object considered in its transitory character, and names this type of symbolism “time-bound reality” or “time-reality”13.

Subsequently, C. H. de Goeje lists the meanings or specific meanings of the morpheme wa in different words, from which we present a wide selection14:

- ‘No making headway’, ‘lasting‘.

- ‘In itself‘.

- ‘Separate‘, ‘independent‘.

- ‘Abnormal appearance‘.

- ‘Curved‘.

- ‘Contracted‘, ‘contracting‘, ‘to be dry‘, ‘pineth away‘).

- ‘Vast‘. (‘we’ is a variant of this meaning).

- ‘Distant‘, ‘far away‘.

- ‘Exceeding‘.

- ‘Length‘.

- ‘To go about‘, ‘to seek‘.

- ‘Very‘, ‘exceedingly‘.

- ‘To be consenting‘, ‘to praise‘.

In order to establish the possible presence of some of these meanings in words from Island Arawak that entered the Spanish spoken in Cuba, we made a selection of 6 such words, which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Selection of words from Island Arawak that entered the Spanish spoken in Cuba with the morpheme gua in its structure, grouped by lexical fields and with its referent. Taken from Valdés Bernal, 199115 and from the Geographical Dictionary of Cuba16.

| Aruaquisms | Referent |

| Guao | Comocladia platyphylla. |

| Guaguao | Capsicum frutescens var. baccatum (Linneo). |

| Guano | Generic name for palms with fan-shaped leaves. |

| Material culture | |

| Guamo | Snail used as a trumpet. |

| Guayo | Scratching instrument. |

| Toponymy | |

| Guane | Plain located in the western end of Cuba, in the province of Pinar del Río. |

Guao

This name is used in Cuba for Comocladia platyphylla (Figure 1) and also for other phytotoxic species such as Comoclaida dentata, Comocladia intermedia, Metopium toxiferum and Metopium venosum (Anacardiaceae)17. They are native to savannas, coasts and stony soils and according to Ricardo et. al:

They are characterized for being caustic and toxic plants; the injuries they generally cause are in correspondence with the sensitivity of the people to their toxicity, in this case, it is very dangerous to approach these plants, some of them just by being exposed to the emanation of volatile substances produce inflammations or ulcerations in the body, which can be more or less serious, depending on the hour and duration of the exposure, when it is at noon the damages are greater. Latex is very caustic and produces serious burns, in those people who are not very sensitive it only stains the skin with a very dark brown or black color18.

Figure 1

Guao (Comocladia platyphylla)

The guao and its toxic effects attracted the early attention of the Spanish colonizers. The chroniclers Fernandez de Oviedo19 and Bartolomé de Las Casas20 mentioned it in their chronicles using the aboriginal name.

The word guao can be segmented as follows: gua +ao = guao, where a vowel /a/ is eliminated by ellipsis.

Regarding the morpheme ao, in a previous entry (Cauto, the river and the name) we showed that it means ‘space’ in Island Arawak.

As for the meaning of the morpheme gua in this case, we will start from the hypothesis that the name is related to the toxic effects produced by the plant, its most striking and relevant characteristic for humans. These effects are distinguished by the inflammation of the skin and the appearance of vesicles and blisters, among other types of lesions. Among the specific meanings of the morpheme gua in Lokono, there are two that fit the description of these pathological manifestations: ‘abnormal appearance’, since the affected skin area takes on a different appearance than usual, and ‘curved’, since the inflamed areas of the skin, as well as the vesicles and blisters have a curved shape.

Thus, gua, ‘abnormal appearance’, ‘curved’ + ao, ‘space’ = guao, ‘abnormal and curved space’. Everything indicates that guao was the word used in Island Arawak to denote inflammation and blisters, so in the first instance guao means ‘inflammation’, ‘blister’, and the plant is named in that form for its property to generate these alterations in the skin.

Guaguao

Capsicum frutescens is known in Cuba as ají guaguao or ají picante. It is a shrub of the Solanaceae family that reaches up to one meter in height. Its fruits are small, between 2 and 5 cm long (Figure 2). It is used as a condiment and in natural medicine. Contact with the skin causes intense burning and overdosing causes irritation, inflammation and blistering.

Figura 2

Guaguao (Capsicum frutescens)

In the structure of guaguao, we can see the reduplication of the segment guao where a phoneme /o/ is eliminated by ellipsis, guao + guao = guaguao. It is evident that the word guao, ‘inflammation’, ‘blister’, is used in this case for the same reasons as in the aboriginal name of Comocladia playphylla, since guaguao causes the same effects on the skin.

The reduplication in Lokono, besides indicating a greater intensity of a state or quality, is also used to indicate repetition or plurality21. In our opinion, in the case of the Island Arawak word guaguao, it is related to the intense sensation it provokes in the mouth or skin, which could be described as a tingling that is repeated in a pulsating manner, which accompanies the inflammation.

Guano

The dictionary of the Spanish language of the RAE defines guano, in its first meaning, as the “generic name of palms with tall, round trunks, without branches, with fan-shaped leaves. The trunk of some species is used to make stakes, fence posts, piles, etc., and the leaves serve as a roof covering”. In its second meaning, it registers it with the meaning of “dry leaves or fronds of the palms”22.

These leaves or fronds were used by the Taino aborigines for the roofs of their dwellings and are still used for the same purpose in the Cuban countryside. They are also used to build the roofs of other larger rustic constructions for gastronomic and recreational facilities, called ranchón.

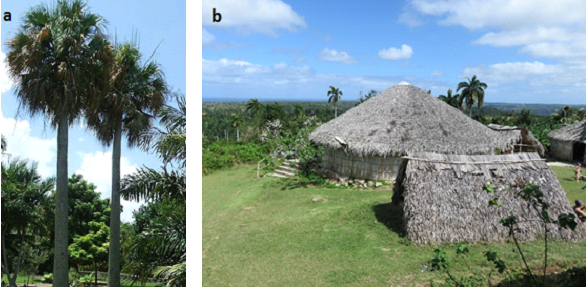

Figure 3a shows specimens of the species known as palma cana (sabal causarium), whose leaves are among the best for roofs. Figure 3b shows Taino constructions with guano roofs, recreated in the locality of Chorro de Maita, Holguín.

Figure 3

Specimens of palma cana -sabal causarium- (a) and Taino constructions with guano roof, recreated in Chorro de Maita, Holguín, Cuba (b).

b) Photo: Ineilands / CC BY-SA 4.0

In the structure of the word guano, the morphemes gua and –no are distinguished. Regarding the latter, it is a pluralizing suffix that is also found in the word Taino, registered early on by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera23. C. H. de Goeje records the suffix –no in Lokono with the meaning: ‘plurality (two or more) of rational beings’24.

Concerning the meaning of the morpheme gua in this word, we start from the hypothesis that it is related to the use of the fan-shaped leaves of the different types of palms to build the roof of the aborigines’ dwellings. Sheltered under this type of roof, they protected themselves from the elements and kept themselves dry, which is why they named guano, ‘dry’ to this type of leaves and palms.

Thus, gua, ‘dry’ + –no, ‘pluralizing suffix’ = guano, ‘dry’.

Guamo

The word guamo was registered in Cuban popular speech for the first time in 1849 by the lexicographer Esteban Pichardo, who pointed out its aboriginal origin25. Alfredo Zayas describes it as “a large conch shell of the kind called cobo, perforated at one end to produce, blowing inside it, a loud and brassy sound”26 (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Cobo (Strombus gigas)

The Swedish anthropologist, Sven Loven, in his work Origins of the Tainian Culture, indicates that, although in the historical literature nothing is said about the use of conch trumpets among the Tainos, the archaeological findings of specimens in Cuba and other places of the Antilles evidence that they knew them. This author describes their use by the Island Caribs, as instruments to transmit signals in war, fishing and hunting. He also quotes the missionary Raymond Breton, who lived among the Caribs, who refers that when a canoe sailing at night was about to dock on the coast, one of the crew members would use the guamo to signal the people on land to light a fire in order to guide the boat27. The use of the guamo must have been similar among the Island Arawaks. It is currently used as a folkloric musical instrument, a use that was presumably inherited from the aborigines.

In the structure of guamo, the morphemes gua and mo are distinguished. The use of this instrument to establish communication between places separated by long distances indicates that in this case gua means ‘distant’.

As for the morpheme mo, in Lokono the expression mo-tu has several meanings related to the action of ‘gathering’:

- Combines two or more persons previously indicated, in a group28.

- It groups several individuals or objects in a category, giving rise to the meaning ‘such’, ‘type’, ‘class’29.

The expression mo-tu is composed of the root mo and the suffix -tu, the latter we have analyzed in several previous entries and is a suffix derived from the word oto, ‘daughter’, which is used to form substantive adjectives and attributive adjectives, as for example, wádin, ‘to be long’; wáditu, ‘the large’; ikihi, ‘fire’; ikihi-tu kaspara, ‘a flaming sword’30.

Thus, in Lokono, the morpheme mo means ‘gathering’.

Therefore, in Island Arawak, gua, ‘distant’ + mo, ‘gathering’= guamo, ‘gathering of the distant’.

Guayo

Esteban Pichardo includes this indigenous word with the meaning: “the quadrilateral table sown with siliceous pebbles or sandstone, on which the yucca is scratched”31 (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Aboriginal guayo

Photo: Daniel Torres Etayo32

In the structure of guayo, the morphemes gua and –yo are seen. The first, in this case, means ‘separate’, ‘independent’, ‘piece’, because when grated, the mass of the tubers is divided into small fragments. As for the suffix -yo, it is a form of the word oyo, iyu, ‘mother’33. Thus, gua, ‘piece’ + –yo, ‘mother’ = guayo, ‘mother of the piece’, ‘producer of the piece’, a name that highlights the function of the instrument to create independent fragments from something originally whole.

Guane

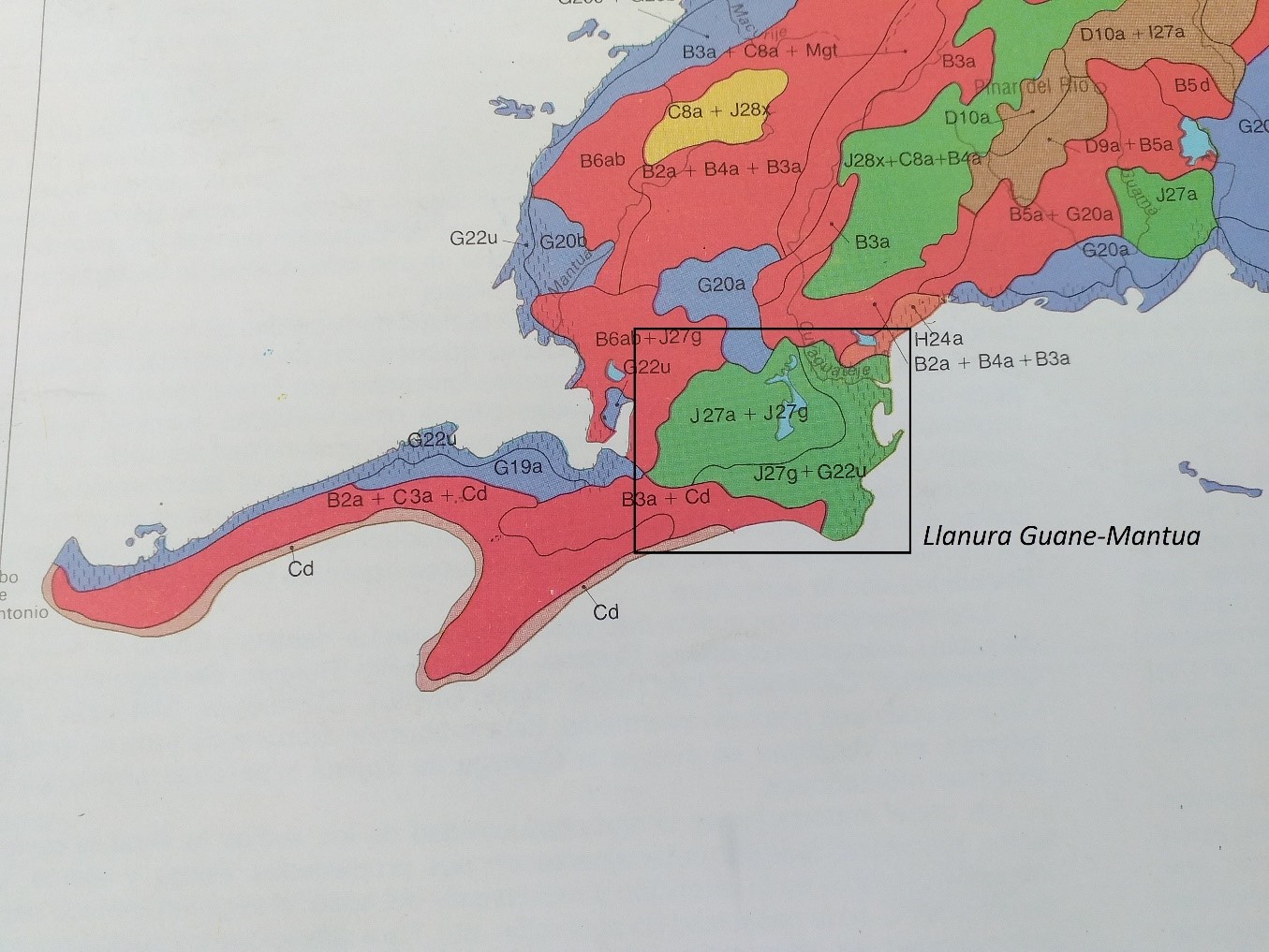

It is a plain located at the western end of the island of Cuba, which is distinguished by its sandy soils. According to the Diccionario Geográfico de Cuba, it is formed by alluvial deposits of the upper middle Pleistocene and constitutes an accumulative, flat, partially swampy lake and marsh plain34.

Figure 6

Soils of the Guane-Mantua plain, according to the New National Atlas of Cuba (1989).

Modified from the Map of soils of the New National Atlas of Cuba. 1989.

It is the characteristic of having sandy soils, which is the motivation for the aboriginal name of this Cuban locality. In the structure of Guane, the morphemes gua and –ne are identified. The first means in this case, ‘separated’, ‘divided’, because the sand is formed by an infinity of different particles of very small size. On the other hand, -ne is an emphatic suffix that in Lokono adds to the meaning of the word the principle of “something that really is or must be ”35. Thus, gua, ‘separated’, ‘divided’ + -ne, ‘in reality’ = guane, ‘really divided’, ‘very divided’, literal meaning used to name the sand. Therefore, in the context of the case we are analyzing, Guane means ‘sand’.

Other aboriginal toponyms in Cuba’s geography that name sandy or swampy places are derived from the word guane, such as Guaney (beach and point in the municipality of Esmeralda, Camagüey), Siguaney (locality in the municipality of Taguasco, province of Sancti Spíritus), Siguanea (cove on the Isle of Youth). In all of them the presence of the guane segment in its structure can be appreciated.

References:

- Valdés Bernal, Sergio. 2010. “El poblamiento precolombino del archipiélago cubano y su posterior repercusión en el español hablado en Cuba” [“The pre-Columbian Settlement of the Cuban Archipelago and its Subsequent Impact on the Spanish Spoken in Cuba”]. En Contextos. Estudios de humanidades y ciencias sociales. NO.24. Página 126.

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. “Décadas del nuevo mundo” [“Decades of the New World”]. Década Tercera. Libro VII. Capítulo III. En Fuentes históricas sobre Colón y América. Pedro Mártir de Anglería. Madrid. Tomo Segundo. Página 397.

- Bachiller y Morales, Antonio. 1883. Cuba primitiva [Primitive Cuba]. Página 271. La Habana.

- Coll y Toste, Cayetano. 1897. Prehistoria de Puerto Rico [Prehistory of Puerto Rico]. Editorial Vasco Américana, S.A. Bilbao. Página 216.

- Zayas y Alfonso, Alfredo. 1914. Lexicografía Antillana [Antillean Lexicography]. La Habana. Página 223.

- Brinton, Daniel Garrison. 1871. The Arawak Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological Relations. McCalla & Stavely, Printers, Philadelphia.

- Kouwenberg, Silvia. 2010. “Taino’s linguistic afiliation with mainland Arawak”. En Proceedings of the Twenty-Second Congress of the International Association for Caribbean Archaeology (IACA). The Jamaica National Heritage Trust. Kingston. https://www.researchgate.net

- Brinton, Daniel Garrison. 1871. Obra citada. Página 12.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1939. “Nouvel examen des langues des Antilles: avec notes sur les langues Arawak-Maipure et Caribes et vocabulaires Shebayo et Guayana (Guyane)”. En Journal de la Société des américanistes, NOUVELLE SÉRIE. Vol. 31. No. 1 (1939). Página 16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24601998.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. The Arawak Language of Guiana. Cambridge University Press. New York. Páginas 158-165. www.cambridge.org.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1970. “Para la historia de las voces“conuco” y “guajiro” [“For the History of the Words “Conuco” and “Guajiro”]. En el Boletín de la Real Academia Española. L, cuaderno CXC, mayo-agosto. Páginas 337-348.

- Arrom, José Juan. 1975. Mitología y artes prehispánicas de las Antillas [Mythology and Pre-Hispanic Arts of the Antilles]. Editorial Siglo XXI. México. Páginas 45-54.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Página 158.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Páginas 158-165.

- Valdés Bernal, Sergio. 1991. Las lenguas indígenas de América y el español de Cuba [The Indigenous Languages of the Americas and the Spanish of Cuba]. Editorial Academia, La Habana.

- Comisión Nacional de Nombres Geográficos. 2000. Diccionario Geográfico de Cuba [Geographical Dictionary of Cuba]. La Habana.

- Ricardo Nápoles, Nancy Esther et al. 2021. “Especies fitotóxicas, Cuba” [“Phytotoxic Species, Cuba”.]. En Acta botánica cubana 196. Páginas 30-39. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352552781.

- Ricardo Nápoles, Nancy Esther et al. 2021. Obra citada.

- Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo. 1853. Historia general y natural de las Indias, islas y tierra-firme del mar océano [General and Natural History of the Indies: Islands and Mainland of the Ocean]. Real Academia de Historia. Madrid. Parte Primera. Libro IX. Capítulo XXXIV. http://books.google.com.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé. 1909. “Apologética historia de las Indias” [“Apologetic history of the Indies”]. En Serrano y Sanz. Historiadores de Indias, TI. Página 37. Madrid. https://archive.org.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Página 133.

- Real Academia Española. 2014. Diccionario de la lengua española [Dictionary of the Spanish Language]. Vigesimotercera edición.

- Mártir de Anglería, Pedro. 1892. Obra citada. Página 397.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Página 119.

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1849. Diccionario provincial casi-razonado de voces cubanas [Quasi-reasoned Provincial Dictionary of Cuban Voices]. Segunda edición. La Habana. Página 100. http://books.google.com.

- Zayas y Alfonso, Alfredo. 1914. Obra citada. Página 250.

- Loven, Sven. 1935. Origin of the Tainan Culture, West Indies. Göteborg. Páginas 495-496. www.cubaarqueologica.org.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Páginas 112-113.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Páginas 127, 179 .

- Hermanos Moravos. 1882. “Arawakisch-Deutches Wörterbuch, Abschrift eines im Besitze der Herrnhuter Bruder-Unität bei Zittau sich befindlichen-Manuscriptes”. En Grammaires et Vocabulaires Roucouyene, Arrouague, Piapoco et D’autre Langues de la Région des Guyanes, par MM. J. Crevaux, P. Sagot, L. Adam. Paris, Maisonneuve et Cie, Libraries-Editeurs. Páginas. 175, 177

- Pichardo, Esteban. 1875. Diccionario provincial casi-razonado de voces y frases cubanas [Quasi-reasoned Provincial Dictionary of Cuban Voices]. Tercera edición. La Habana. Página 184. http://books.google.com.

- Torres Etayo, Daniel. 2006. Taínos: mitos y realidades de un pueblo sin rostro [Tainos: Myths and Realities of a Faceless People]. www.cubaarqueologica.org.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Páginas 167, 193.

- Comisión Nacional de Nombres Geográficos. 2000. Obra citada.

- Goeje, Claudius Henricus de. 1928. Obra citada. Páginas 35, 77.